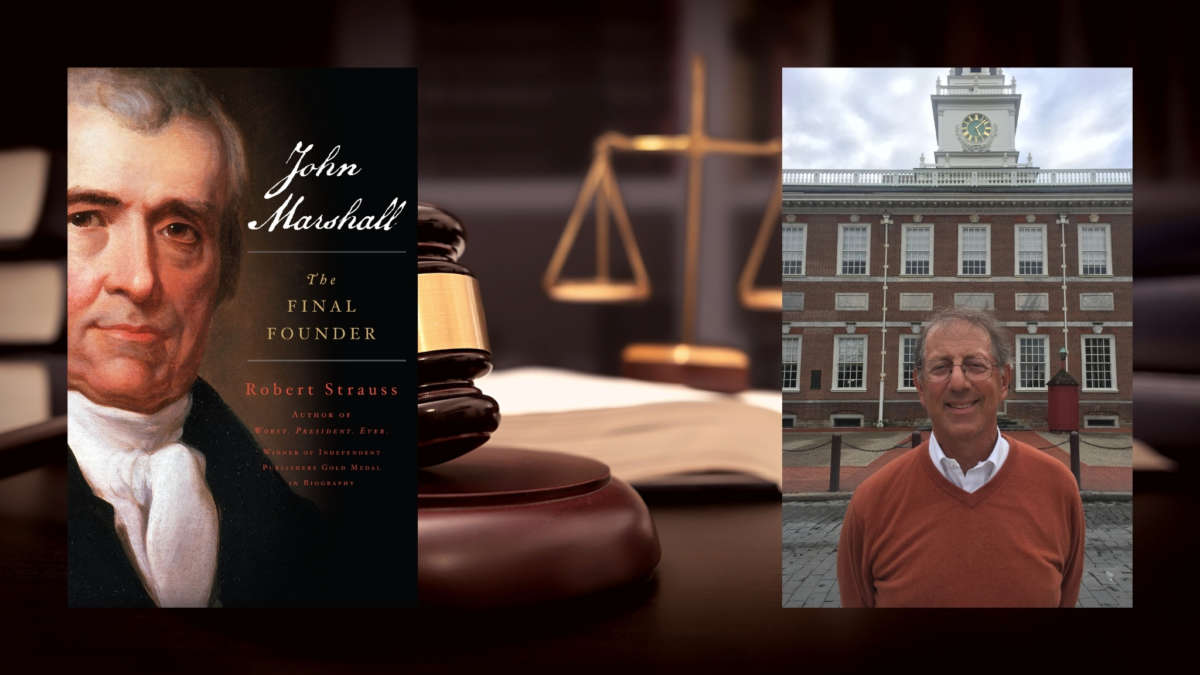

John Marshall: The Final Founder (Lyons Press) by eminent scholar Robert Strauss boasts “entertaining historical tidbits within a fine short biography,” according to Kirkus Reviews, and is about one of the greatest historical figures ever, according to my college-history-professor Dad.

George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin — these are names we all know well, the names of the people who established the structure of our nation as we know it today. Another name should be added to the list, argues Strauss. John Marshall became the fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, taking office at the turn of the 19th century, 1801. He instigated many policies that have shaped not only the Supreme Court but our entire government, and devoted his life to fortifying the judicial branch.

The Supreme Court has been a prominent subject of current political discussion. To fully understand the predicaments that the modern court faces, it behooves us to do our research and familiarize ourselves with its history.

Jess Kastner had the opportunity to pick the author’s brain and offer us a glimpse into his forthcoming biography.

Q: Is Marshall a figure like Hamilton, who was incredibly famous in his day and just barely in ours?

A: Yes is the short answer. But basically, he was everywhere — the Forrest Gump of the Founders — from Valley Forge, to convincing Virginia to pass the Constitution, to U.S. Congress, to writing the first bio of George Washington, to cementing our neutralist foreign policy by not relenting to French demands in the XYZ Affair, to acting as Secretary of State under Adams (who had him supervise the building of Washington, DC), to his long Supreme Court tenure.

Q: Why do you consider Marshall to be the figure who saved the nation?

A: By making the Supreme Court stronger, and showing how it could bridge what seemed like an unsolvable divide between Congress and the President, he made a three-way check and balance system that, even when people complain about it, has made our democracy viable.

Q: Why was it easier than people imagine to be a Founding Father?

A: The country was not very populated but was really spread out. Even then, people often moved on to find land of their own, away from “civilization.” When Marshall came to Richmond, he soon became the most prominent lawyer there — but then there were only 2,600 people who lived there. So he got to take that first step, which led to being in the state legislature and then Congress, then hobnobbing with anyone who was anybody — Washington, Adams, and so forth. By the time he became Secretary of State, he was naturally considered a Presidential possibility. He took the Supreme Court post, however, and from there he became legendary to those who study the Constitution.

Q: How was Marshall’s Supreme Court different from today’s?

A: He had them meet where they could — first in the basement of the new Capitol, and then sometimes in a boarding house nearby when a member was ill. He insisted on unanimous decisions, noting that each would take a turn on the low side at some point, but to accept the majority opinion in unanimity solidified the Court’s overall standing. Marshall wrote almost all of the decisions, whether he agreed with them or not — though he would often assign one of those to a “victor.” Even when the Court became majority Democrat — he was a Federalist — his influence made unanimity the precedent, though that is clearly not so today. In Brown v. the Board of Education, Chief Justice Earl Warren harkened back to Marshall and thought only a unanimous vote would allow the case to be applied nationwide.

Q: One of the essays within is named “When did the Founding end?” When was that?

A: Other historians quote anything from the signing of the Constitution to the last days of the rule of those present at the Founding to the end of John Quincy Adams’s term. I choose Marshall’s decision in Marbury v. Madison, which allowed the Supreme Court to void a law; only then were the branches co-equal and the government closer to what it has been over time.

Q: Why is Marshall so venerated among judges and lawyers?

A: The actual legal decisions — which of the sides “won” — were less important to him than a point made. He had 34 years of making decisions, so there is a lot of seminal law to go through. His statue graces the entryway to the Supreme Court chambers and each new justice gets to sit in his chair — taken out of the Supreme Court museum for the ceremony — when he or she gets sworn in. Because of him, the portraits of James Madison and William Marbury, the defendant and plaintiff of the Court’s seminal case, hang in the antechamber of the Court.

Q: Who were his friends and enemies?

A: Thomas Jefferson was his second cousin, through the Randolph family, and Marshall’s father-in-law married a woman who rebuffed Jefferson’s early romantic advances. But more importantly, Marshall was just more popular and also had a different philosophy, being the last Federalist while Jefferson was the most prominent Republican-Democrat. Marshall also, as the Justice covering the Virginia circuit, presided over an early treason case against Aaron Burr. Marshall was George Washington’s prominent acolyte, serving under him at Valley Forge and ending up writing Washington’s first biography (which was actually pretty dull and never venerated).

Q: In another essay, you write about how we don’t understand the constraints of place and time during the 18th and 19th Centuries. How did it affect Marshall and the other Founders?

A: Washington died on December 14, 1799, and the official letter announcing his death did not get to Marshall, his emissary in Congress, until four days later. There was no I-95 linking Mount Vernon and Washington to Philadelphia. In fact, there was no Washington. There was a decent road between Boston and Philadelphia, but even then, trees and huge potholes were bad obstacles for the carriages to maneuver around. If a horse ran off, or a wheel broke, you pretty much had to wait until someone came by.

Pondering that, how did those patriots in Georgia know what the ones in New Hampshire were doing when it took weeks to get a message through? If Congress wrote to Jefferson in France to do this or that, it might take a month to get the word out. How did he know whether it was still necessary? There were only seven post offices in all of New Jersey and only one south of Trenton. There were no “addresses,” and postmasters basically had to read everything to get it to the right place. Imagine the lack of secrecy and security! Furthermore, there was only one city with more than 20,000 people — Philadelphia, with 40,000 — when the Declaration was being written. It was an incredibly rural nation, and so those who actually got to Philly did what they wanted; do we really know how everyone felt about it, though?

Q: What is the fate of the Supreme Court, vis-a-vis Marshall or otherwise?

A: As of today, the overwhelmingly conservative leaning of the Court means that it is often behind the times. That may not be so bad; there has to be some sort of acknowledgment of historical precedent somewhere in the government. It was slightly an afterthought at the Constitutional Convention, but if there was a thought, it was that lifetime appointments made the country realize it would have a history. There have been more justices who have swayed left in their terms — Earl Warren, Hugo Black, Harry Blackmun, Sandra Day O’Connor, David Souter and John Paul Stevens come to mind in recent decades — than have swayed right. Perhaps being more venerable makes them more relaxed. Also, since they have no one to impress but themselves — eight of the nine went to either Yale or Harvard in some form — they are the most elite part of any government.

Q: What was different about Marshall?

A: He was generally happy in his life. He met his wife when she was 13; he was in his 20s and a war veteran. He loved her immediately, and even when she became a recluse, he came home from Washington, Richmond and Philadelphia often to comfort her. He loved to give parties and was generous with his stash of prime Madeira, the elixir of early America. He did have slaves at times, but often freed them and bought new ones when he needed to. Were he alive today, he might be a bit less eager to have that known. He chose few close friends but had many casual ones. His favorite place was the Quoits Club he started in Richmond, and after he died, the club decreed that there would always be one less member to honor him just the way he would have wanted.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Robert-Strauss-author-photo-scaled.jpg

About Robert Strauss:

Robert Strauss has been a reporter at Sports Illustrated, a feature writer for The Philadelphia Daily News, a news and sports producer for KYW-TV, the NBC affiliate in Philadelphia, and the TV critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer and Asbury Park Press. For the last two decades, he has been a freelance journalist, his most prominent client being The New York Times, where he has had more than 1000 bylines. He has taught non-fiction writing at the University of Pennsylvania since 1999 and been an adjunct professor at Temple University, the University of Delaware, and St. Joseph’s University as well. He is the author of Worst. President. Ever. among other books. He lives in Haddonfield, New Jersey.