The Gustav Sonata by Rose Tremain

Set in Switzerland during World War II , Rose Tremain’s literary masterpiece, The Gustav Sonata, follows the life of Gustav Perle, who is taught at a young age by his mother to master himself, and his emotions – to be neutral like Switzerland in the war. When he begins a friendship with Anton, the young Jewish boy and piano-playing prodigy in his class, Gustav is instantly struck by the comparison between Anton’s supportive and loving family life, and his own, colder relationship with his mother; what begins as an unlikely childhood friendship, becomes a lifelong relationship. Spanning six decades, this novel is a heartbreaking, wonderful story of conscience, friendship, love, and the consequences and legacy of war.

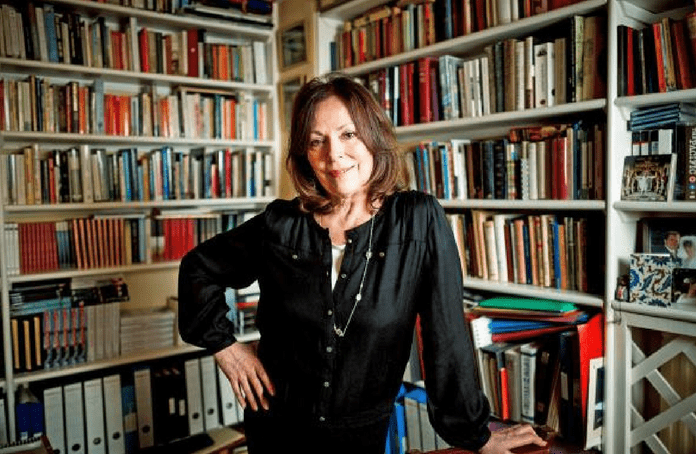

Booktrib recently interviewed Rose Tremain about her novel, writing complex characters, Switzerland, and

Booktrib: The Gustav Sonata is such a masterful novel – not just in the way it’s written, but in the characters and the story you’ve created. What first drove you to write this novel? Was there a theme, or an idea that you just couldn’t let go of?

RT: In direct contradiction to what I used to tell my creative writing students at the University of East Anglia – that a short story can NEVER turn itself into a novel – The Gustav Sonata actually began a long time ago as a short story entitled A Game of Cards, published in Areté in 2007. The story sets out some of the themes explored in the novel, but doesn’t capture any of them as vividly or as deeply as I would wish. So yes, along the length of many years, I had the feeling that there was a great deal more to say about Gustav and Anton, about Swiss neutrality, about friendship and about the plight of Jewish refugees fleeing Germany in 1938. Indeed, the Jewish element, and in particular Erich Perle’s defiance of authority in order to save Jewish lives, so central to the novel, wasn’t really there in the story, so it was like a body with a missing limb.

Booktrib: Typically with books set in WWII, they’re set in Germany, Austria, England, France – countries that were very actively involved in the war. But you have your novel set in Switzerland, which I feel like people don’t really know much about the history of during WWII. Tell us a bit about why you chose to set the novel here.

RT: I was fascinated by the way the Swiss wrestled with their neutrality when the Second World War began. Being a nation comprising three nationalities, French, Italian, and German, Switzerland had to try to stay neutral, or else be a country at war with itself. I think people assume that this neutrality was reasonably easy to maintain, but in fact, the Swiss just couldn’t be certain that Germany wouldn’t invade, and there was huge anxiety and fear about this, which, in turn, affected the Swiss-Jewish refugee policy. To try to capture some of the contradictions inherent in Switzerland itself – its beauty and compulsion towards orderliness, as well as its mercantile spirit was a fascinating task. I also wanted to go against the way Switzerland is imagined in most readers’ minds (mountains, blue skies, cow bells, edelweiss, immaculate and prosperous cities, happy bankers), and create an ordinary little town, where most people are struggling to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

Booktrib: In the very beginning of the novel, you introduce the idea of Gustav “mastering himself” – putting on a show of indifference, of masking emotions, in situations of high emotion. I’m curious about your choice of words here – how did you come up with this concept, and choose to express it like this?

RT: I found the term ‘self-mastery’, (Selbstbeherrschung) a Swiss-German concept denoting both self-control and self-reliance, to be absolutely perfect for what the character of Gustav has to achieve. I like the irony that it is Emilie, Gustav’s mother, who shows him very little affection, who orders him to conduct himself in this way. If she had been able to love him, he wouldn’t have had to be so self-disciplining and fierce with himself. Yet, his self-mastery is the thing which enables him not to break down at the loss of his friend Anton and to carry on with a small, orderly life until some resolution of his love can be reached. I came to admire the stoic in Gustav and to agree with his world view about life being made bearable by the existence of small pleasures and comforts.

Booktrib: Emilie is such an interesting, dynamic character. From the very first page, you get the idea that she’s a very practical, very careful character; yet at the same time, she’s also someone who is incredibly emotional and feeling. Can you tell us a little bit about the character, and what she means to you?

RT: Emilie was complex and fascinating to write. She’s a victim of two things: her mother’s inability to love her and her own selfish ignorance about the world. The first accounts, in some measure, for her failure to nurture Gustav; the second brings about her husband’s only moment of violence towards her, which in turn causes the miscarriage of her first baby, also named Gustav. I think there was a danger to making Emilie into a character whom we dislike so much that we don’t really care what happens to her. To offset this potential antipathy, I underscore for the reader the tragic quality of her life, which is blighted by so much that she doesn’t understand. I think the scene in which Emilie tears open a cushion and begins showering feathers all over herself captures both her own childish inadequacy and her role as victim in a world she fails to comprehend.

Booktrib: There’s a chapter in Part One – it’s actually the last chapter, titled Magic Mountain, which immediately draws parallels with Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain – the chapter and the book are in the same place, with the same elements involved, though his was set in the time period before WWI. Mann’s book is actually referenced throughout The Gustav Sonata. I’m really curious about why and how you decided to draw this parallel or association between the two.

RT: In this classic, difficult and beautiful novel, the protagonist, Hans Castorp, with the collusion of his doctor, Hofrat Behrens, prolongs his own illness in order to linger on at a Davos Sanatorium rather than free himself from his obsessions and go out into the wider world. Gustav’s choice of a life in the confines of a protected place mirrors Hans’s, to some degree. So it felt right to me to let the shadow of The Magic Mountain fall across my endeavour. From Mann’s novel, one takes the idea of the Davos sanatorium as a place where learning happens via an understanding of suffering, and where fate plays itself out. I was thus able to conceive the scene you refer to, which takes place in Davos, in an abandoned hospital, where Gustav and Anton act out dramas of love and death – Gustav knowing already that their love for each other is a love-and-death matter, and Anton not yet able to understand this.

Booktrib: Hans, Gustav and Anton are such complex, rich characters, and we [the readers] get to see what is almost their entire lives played out; we see the interactions they have on each other, and the impact of their relationships. Can you tell us a little bit about the friendships and relationships between the three of them?

RT: Mann has stated that ‘what Hans came to understand is that one must go through deep experience of sickness and death to arrive at higher sanity and health’; in other words, the individual has to grapple with the totality of existence, in all its complexity and terror, in order to arrive at any kind of personal sanity. What I set out for Gustav and Anton is the following conundrum: Gustav totally grasps the truth of Hans’s realisation, but chooses to remain in his small life, rather than follow where it leads; Anton doesn’t understand it at all, yet he is the one who embarks on a dangerous life of ‘sickness and death’ , only narrowly escaping actual death by his late revelation that Gustav is the only person who can save his sanity. Hans Castorp escapes the sanatorium at the end of the novel, to be drawn, in all probability, onto the battle fields of the First World War, whereas Gustav and Anton arrive together at an era of peaceful co-existence. They come through.

Booktrib: Finally, do you have any tips for other writers, or writers who are just starting out?

RT: Ignore the old instruction “write about what you know”! For why do this, when you probably don’t know very much yet? Instead, find a subject that is knowable and immerse yourself in that, and then find a way of using that as a source and inspiration for your fiction. In this way, you are learning as well as teaching, as you go along.

For more information on author Rose Tremain, please visit her website at rosetremain.co.uk

Buy this Book!

Amazon