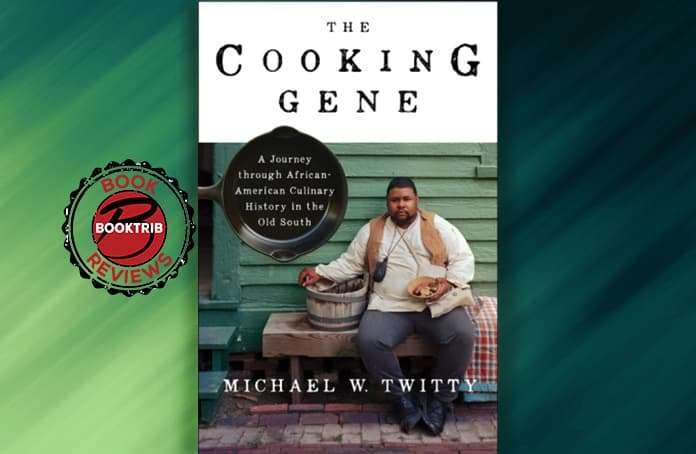

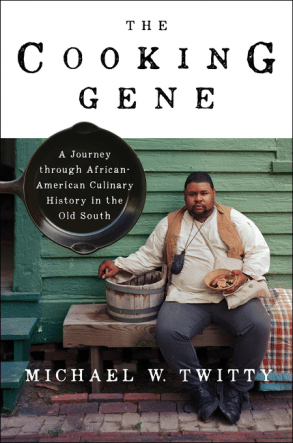

The Cooking Gene by Michael W. Twitty

Like the author himself, The Cooking Gene (Amistad, August 1, 2017) by Michael W. Twitty defies easy categorization. Not quite a memoir, nor historical nonfiction, nor a cookbook, it combines elements of all three to take us on a historical journey that shows how African foodways formed and informed the American diet and how the history of a people can be writ large in the food they ate.

When Twitty approached publishers about his work as a culinary historian investigating the African-American roots of Southern cuisine, he was told that his identity was too complex and his work didn’t fit neatly into any one genre. But his unique, intersectional perspective as an African-American gay Jew brings insight to every facet of The Cooking Gene. Twitty explores avenues often overlooked in the development of Southern cooking by examining the very elements of his existence— from his family history to the food he grew up with to his DNA. As Twitty writes, “It’s as if by cooking you have crossed a boundary, and the dance of pounding, kneading, sweating, choking, and sweating connects with something timeless, all of the movements that came before you become you.”

When Twitty approached publishers about his work as a culinary historian investigating the African-American roots of Southern cuisine, he was told that his identity was too complex and his work didn’t fit neatly into any one genre. But his unique, intersectional perspective as an African-American gay Jew brings insight to every facet of The Cooking Gene. Twitty explores avenues often overlooked in the development of Southern cooking by examining the very elements of his existence— from his family history to the food he grew up with to his DNA. As Twitty writes, “It’s as if by cooking you have crossed a boundary, and the dance of pounding, kneading, sweating, choking, and sweating connects with something timeless, all of the movements that came before you become you.”

What is revealed is a nuanced and complex picture of a country’s history through our food by teasing apart the traditional foods and cooking styles of African, Native American and European traditions. Twitty doesn’t flinch from hard truths that he discovers along the way—the crops that made America great and fueled bellies and the national economy were often brutal to the enslaved. Rice and sugar cane were sources of backbreaking and often deadly labor. Cotton drove the enslaved deeper into misery and forced a waning slave trade back into high demand.

Twitty traces the twisting and tangled trail of how the peoples of West Africa adapted to what they encountered, by seizing the familiar, adapting to new foods, and elevating the recipes they were taught. He learns how Americans are as interrelated as the food they love, discovering white ancestors who connect him to black cousins and a white woman who came to America as an indentured servant and married according to class, not race.

The culinary intersections that make up his identity as a black Jewish man are equally illuminating. “Jewish food and black food crisscross each other throughout history. They are both cuisines where homeland and exile interplay. Ideas and emotions are ingredients—satire, irony, longing, resistance—and you have to eat the food to extract the meaning,” he writes.

Like Twitty himself, The Cooking Gene is far more than the sum of its parts. The poetry of his language empowers the journey of a man who becomes the avatar of what was to become America. He reveals a South that has one foot in its tumultuous history and another in a diverse future.

As Twitty writes: “The Old South is where I cook. The Old South is a place where food tells me where I am. The Old South is a place where food tells me who I am. The Old South is a place where food tells me where we have been. The Old South is where the story of our food might just tell America where it’s going.”

Buy this Book!

Amazon