Committed

“Insanity had taken root in my family tree, and I was tasked with tending our garden,” writes Paolina Milana as she begins Committed: A Memoir of Madness in the Family (She Writes Press). With plans to attend an out-of-state university, a year away from her family promised 20-year-old Paolina respite from her turbulent home life. The physical separation, however, creates little emotional distance as letter after letter arrives, detailing all that’s occurred in her absence. Desperate to live a “normal” life alongside her peers, Paolina keeps her family issues secret all the while fearing that she’ll inherit her mother’s schizophrenia. When her father’s unexpected death leaves Paolina in the position of primary caregiver to her mother, it seems as if the worst has come to pass, but then her younger sister’s psychotic break drops Paolina into new depths of despair. Weaving personal documents such as letters, poems and notes into her memoir, Milana offers readers an epistolary snapshot of her twenties as she confronts tragic loss in a world of overwhelming madness.

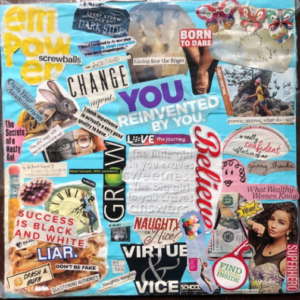

Milana’s vision board

More than thirty years have passed since then. Today, Milana is the founder of Madness to Magic, where she works as an empowerment and resiliency coach. Through her organization, she helps her clients “channel their fears and doubts and anger into courage and strength and determination to realize their full potential. We tap into their already existing power through the use of storytelling techniques.” One of Milana’s favorite activities to complete with her clients is a vision-board-style project with a twist. Instead of focusing solely on aspirations, “we include visuals of the dark and light within us.”

“We all have, within us, both the dark and the light,” says Milana. “We all are both villain and hero, predator and prey. Shaming the ‘bad’ within us only makes that part of us stronger to the detriment of the good. What we resist, persists. But if we embrace all of who we are, we defy gravity. Channel the villain, and we unleash the hero.”

A lot has changed for Milana herself since the events detailed in her memoir, but what, if anything, has changed about the visibility and understanding of mental illness over the last few decades? “If we’re talking ‘perceptions’ surrounding schizophrenia and other mental illnesses,” says Milana, “I think there has been a real effort on the part of individuals and brands.” She notes Philosophy’s Hope & Grace initiative and the forthcoming Apple TV documentary series from Oprah Winfrey and Prince Harry as prime examples. She also mentions that a few fictional representations of mental illness — Ian and Monica Gallagher’s struggles with bipolar disorder on the Showtime series Shameless, an episode of Modern Love starring Anne Hathaway (“Take Me as I Am, Whoever I Am”), and the 2012 film The Silver Linings Playbook — “are among those who are trying to make a difference. From a marketing and media perspective, however, mental illness may still carry with it a sense of fear for people.”

Milana says that “more often than not, mental illness is part of that breaking news,” as with the recent shooting in Boulder, CO. In contrast, she explains that other issues receive more visible, positive attention: “Cause marketing shows us puppies to rescue or kids with cancer or teens who struggle with the realization that they’re gay, and all of that elicits emotions that pull on the heart and purse strings; not so much when it comes to mental illness. Schizophrenia, especially, seems to still be something equated with ‘those people’ we may see on the street talking to themselves or the ‘crazy’ characters who are told by voices to attack. While it has become a more positive narrative in the mainstream, and the movement is toward acceptance and empathy that ‘it’s okay to not be okay,’ I think we still have a lot of room for growth.”

Of course, representations of mental illness — be they positive or negative — were few and far between when Milana was growing up. “Cosa Nostra,” an Italian idiomatic expression directly translated to “our thing,” haunts the author: “My family’s Sicilian roots and the mantra of ‘cosa nostra’ [meant that] ‘what happened in the family stayed in the family’ was our unwritten rule.” She says, “this was long before today’s love affair with Reality TV, so there weren’t any other families visible living in our similar shoes.” As a result, Milana was often isolated from her peers, but she believes that support in the face of struggles like hers is invaluable: “Keeping secrets is what suffocates us. Making it okay to share releases the pressure and helps us find a way to a better place that, on our own, we just can’t.

“‘We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them,’ said Albert Einstein. The same holds true here. When we are in the thick of madness, whatever our particular flavor of it may be, we’re just treading water and all objectivity or sense of possibility is too murky to break through. I would strongly suggest to anyone struggling that they realize the very fact that in order to help others, they must first help themselves … Familial obligations are important, but they also can be damaging. So, reach out to someone … Even just telling someone about your situation can do such good for your emotional state of being. I promise you will not regret it, nor will your family, at the end of the day.”

Cultural perceptions of mental illness aren’t only influenced by the media we consume or by the stories and experiences we share with others. Milana notes that language itself — the use of words like “crazy” and “normal” — plays a huge role in shaping our ideas around mental illness: “I had wanted to title my book using the word ‘crazy,’ and the publisher let me know that, in the current climate, that wasn’t advisable. As a matter of fact, the publisher wouldn’t allow it.” Milana sees this as a problem: “The more we target words and concepts as ‘bad’ or ‘wrong,’ the more we are segregating versus mainstreaming, and the more we are empowering that specific word versus the intent of the speaker. Words aren’t bad … Being ‘crazy’ is OK unless we make it not.”

“When we try to hide or shame ourselves into silence, that is when we start to suffocate and either implode or lash out … Being ‘crazy’ or ‘normal’ is part of who every one of us is. It’s not the word that has the power to negatively influence cultural perceptions; rather, it’s the fact that we have chosen to define them in a certain way. If we all were to acknowledge and embrace that, at any given point in our human existence, we can be both ‘crazy’ and ‘normal’ and a host of other descriptors, then those labels are stripped of their power and just become part of life. And we all become more ‘same’ rather than ‘different’ as a result.”

Through her memoir, Milana hopes to have an impact on her readers’ perceptions and understanding of mental health: “I hope Committed shines a light on mental illness and mental health, shifting the narrative in a way that helps readers realize that at any given moment in anyone’s journey, ‘crazy’ may come calling. And we don’t need to fear it or shame it or deny it or keep it at arm’s length. I hope readers see through my story that it’s the silencing and stuffing down of our madness — whatever that madness might be — that has the power to suffocate and take us down. Sometimes, the strongest among us need help, and I hope caregivers reading this realize that not only is it okay to take a time out and to show themselves the care they give to others, but it’s actually a must. I hope Committed encourages others to speak and to tell their own stories and to feel empowered by doing so.”

As Milana notes at the end of her memoir, the word “committed” has several meanings. Although she touches on each of them in her book, it’s clear that she herself embodies its most unwaveringly positive definition: dedication. Milana is committed to helping others transform their own madness into magic; and her memoir, which vulnerably shares her own experience navigating the darkest parts of life, is a testament to just that.

RELATED POSTS

Dr. Shelley Kolton’s Memoir Uncovers All The Sides of Dissociative Identity Disorder

Memoir “Virtual Insanity” Provides a Minds-Eye View of Schizophrenia

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/PaolinaMilana_PhotoC_JenniferCarrillo-516×550.jpg

Photo Credit: Jennifer Carrillo

About Paolina Milana:

A published author, speaker, podcaster, and founder of Madness To Magic, Paolina Milana’s mission is to share stories that celebrate the triumph of the human spirit and the power that lies within each of us to bring about change for the better. Her professional background includes telling other people’s stories, first as a journalist and then as a PR and digital marketing executive in both corporate and nonprofit environments. She currently serves as a Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) for children in foster care and as an empowerment coach, using storytelling to help people reimagine their lives, write their next chapters, and become the heroes of their own journeys.

Paolina has won awards for her writing and creative campaigns, including her first full-length book The S Word, which received the National Indie Excellence Award. She is first-generation Sicilian, married, and lives on the edge of the Angeles National Forest in Southern California.