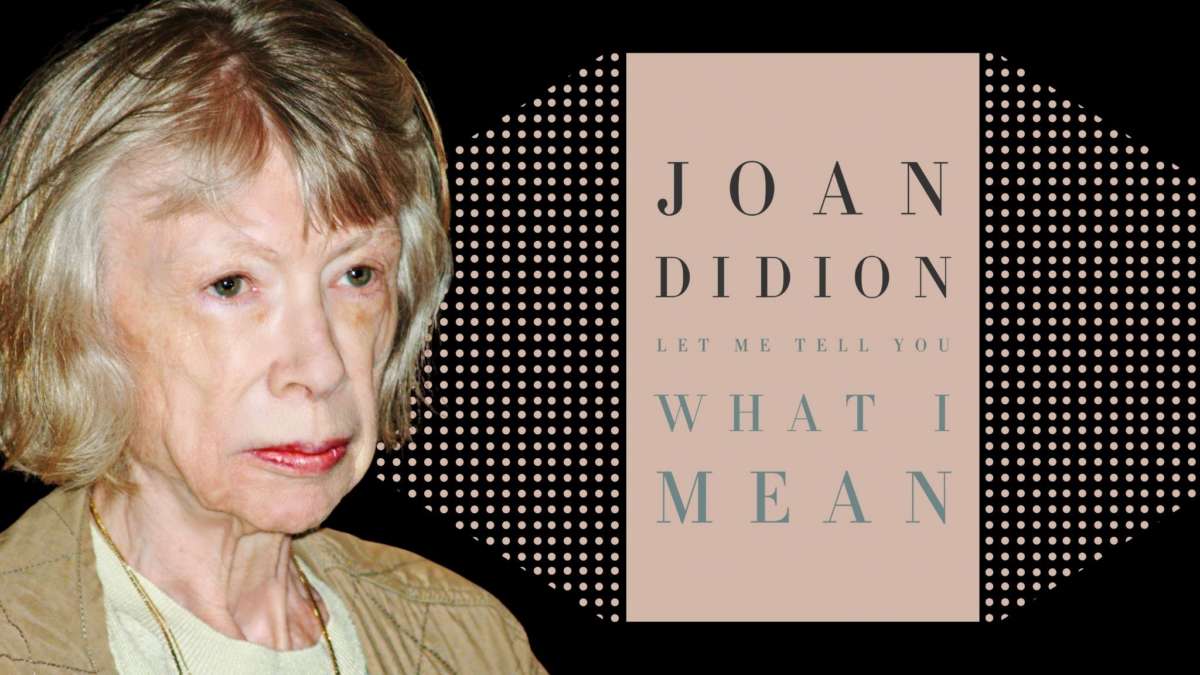

Let Me Tell You What I Mean

I should preface this review with a confession: despite being a born-and-raised Californian, I had never read any Joan Didion until last week. I couldn’t tell you why, except that I’d never had her on a syllabus, never serendipitously stumbled on her in a used bookstore — the opportunity had never presented itself, or maybe I was scared to seek it out, dreading on some level that this iconic voice of my homeland would turn out to be a disappointment.

Over the course of Let Me Tell You What I Mean (Knopf), I was thrilled to discover that my fears were unfounded. And yet I don’t regret not getting into Didion before 2021; otherwise, I would not have been so enthralled by the elegance, astuteness, and foresight of this collection. The last is apparently a Didion trademark, but to a newcomer, the effect was such that several decades-old passages in this book left me breathless with recognition.

Let Me Tell You What I Mean consists of twelve essays spanning thirty-two years, the first written in 1968 and the last in 2000. The topics range from the eerie, passive religiosity of Gamblers Anonymous meetings and the oddly touching contrivances of Nancy Reagan to an impassioned defense of Hemingway’s posthumous literary rights. Though bookended by cultural commentary, the collection also contains Didion’s own reflections on becoming a writer, with a special focus on writerly rejection — a welcome theme because it doesn’t feel falsely humble or patronizing, but as honest and organic as the rest of the collection.

DIDION ON MEDIA, WRITERS AND WRITING

Indeed, much of what makes the earlier essays so strong is how Didion’s worldview — her salt-of-the-earth work ethic and disdain for the superficial — permeates even when she attempts to remove herself. (In the introduction, Hilton Als notes that her perspective has become much more controlled with time, but that a core element of Didion has always been “her refusal to pretend that she doesn’t exist.”) It’s no coincidence that an essay extolling the virtues of the sixties’ “underground press” comes first in the collection, setting us up with the observation that:

To think that these papers are read for “facts” is to misapprehend their appeal […] These papers ignore the conventional newspaper code, say what they mean. They are strident and brash, but they do not irritate; they have the faults of a friend, not a monolith.

Didion’s own writing is rarely, if ever, strident or brash. But to characterize her voice as that of a friend, her writing as candid and often subjective, is perfectly apt. Nowhere is this truer than when she speaks directly to her audience, and nowhere is it more revealing than in her essays on craft. From the first of these, “Why I Write,” adapted from a lecture given in 1975:

In many ways, writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind […] There’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.

A less flattering take on subjectivity, but also not one the reader feels inclined to take very seriously; a writer can hardly trap you in a corner after confessing how she plans to do it. Still, Didion manages this essay after essay — through not so much a trap as a graceful ushering into the corner, where the reader then decides to stay of her own accord.

I didn’t give a whit about Hemingway’s legacy before reading “Last Words,” but by the end of Didion’s unflinching condemnation of his estate’s handling of True At First Light, I was ready to take to the streets. Likewise, I’ve never been much for war stories, but Didion’s account of a WWII veterans’ reunion — infused with the poignancy of one man’s son gone missing in Vietnam — struck an undeniably deep chord. (This narrative conviction, even when telling other people’s stories, makes it clear why Didion is such a successful memoirist.)

PRESCIENT YET TIMELESS OBSERVATIONS

But perhaps even more impressive than the pure persuasion of her voice is how she truly does, at times, seem to peer fifty-plus years into the future. In one standout essay, “On Being Unchosen by the College of One’s Choice,” Didion writes:

Getting into college has become an ugly business, malignant in its consumption and diversion of time and energy and true interests, and not its least deleterious aspect is how children themselves accept it.

At this sentence, I felt equally despondent that so little has changed about US college admissions since 1968 and astonished by the author’s far-sightedness. Another example, from the essay “Some Women,” which Didion begins with a sketch of celebrity photography sessions at Vogue:

What occurred in these sittings […] was a transaction of an entirely opposite kind: success was understood to depend on the extent to which the subject conspired, tacitly, to be not “herself” but whoever and whatever it was that the photographer wanted to see in the lens.

Replace “photographer” with “follower” and this observation could just as easily apply to Instagram in the 21st century. What is success, in any mode of portraiture, if not an elaborate performance tailored to the viewer? Didion not only knew this in 1989, but could throw it out with the casual concision of an expert, positioning it to serve as mere introduction to her main subject (the work of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe).

Powerfully voiced, remarkably prescient: Didion’s signature features, according to her more seasoned reviewers. This collection, they say, rather less noteworthy than the esteemed likes of The Year of Magical Thinking and Play It As It Lays.

But I am no Didion expert, only a novice. Like the author herself in the best of these pieces, I can only convey what I know to be true: Let Me Tell You What I Mean dazzled me. And no matter what else is out there, how many other achievements may reside in her oeuvre, I am immensely, incredibly grateful for this collection to have opened the door.