As the story goes, Andrew Gulli, Managing Editor at The Strand Magazine, was in the midst of research when he came across a work of Shirley Jackson’s that he had never read. Curious, he reached out to her agent and, lo and behold, discovered that the 3,000-word short story had never been published.

Until now.

The Strand this week is releasing the very timely “Adventure on a Bad Night,” as insightful now as it would have been the day Jackson wrote the last sentence.

“By all accounts, it was written after World War II and shows Jackson’s ability to craft something entertaining, insightful and profound out of normal, everyday human experiences,” Gulli says. The story “has her vintage style of creating a cast of characters who feel stuck in the world.”

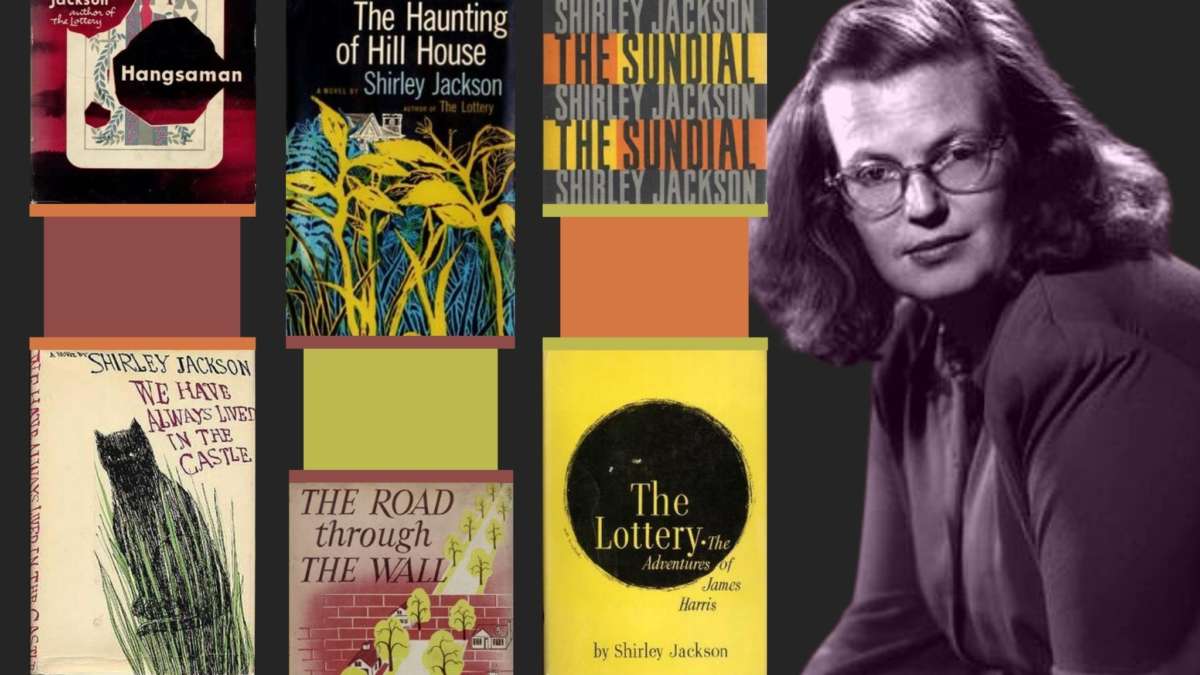

So just how profound was Jackson’s impact on the literary world? A 2016 article in The New Yorker captured the crux of it: “Shirley Jackson…during her lifetime was largely dismissed as a talented purveyor of high-toned horror stories—’Virginia Werewoolf,’ as one critic put it. For most of the 51 years since her death, that reputation has stuck. Today, ‘The Lottery,’ her story of ritual human sacrifice in a New England village [first published in this magazine, in 1948], has become a staple of eighth-grade reading lists, and her novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959) is often mentioned as one of the best ghost stories of all time.”

Shirley Jackson, born in San Francisco on December 14, 1916, was a university-educated woman who wrote inexhaustibly and with a penchant for the horror genre. She achieved an enormous amount before her death in 1965, and her work still draws popular attention. One of her greatest pieces, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, was adapted as a well-received Netflix film in 2018. Meanwhile, Jackson herself inspired the film “Shirley,” released only this past year.

“Adventure on a Bad Night” has its fair share of that slyly sinister disposition which brought her accolades and audiences, while also sporting a clever and refined wit. An excerpt demonstrates the kind of prose found in a Jackson piece:

“‘Don’t trust me, do you, honey?” the clerk said, and Vivien solemnly stood there counting her change while the woman in back of her in line began to call an order over her head. When she took her package and went out she heard the clerk saying “She doesn’t trust me,” and the people laughing. Of course I don’t trust him, Vivien thought, he’s a crook. I wish I could say it. I wish I didn’t have to shop there and none of these other people did either.’”

In passages like this, Jackson offers an impressive myriad of perceptive observations on human nature and society, with an equal portion of drollness and dread. It takes a sharp mind and an ever sharper pen to create such piercing works.

The Shirley Jackson issue of The Strand is available now for purchase on the publication’s website.