In movies and even in books lawyers are always warning people not to confess to them, but in real life it doesn’t work that way. In real life you want to hear everything you can and later on you’ll make whatever compromises you have to, or you won’t. That’s the essence of the job, making that decision quickly and then living with the consequences.

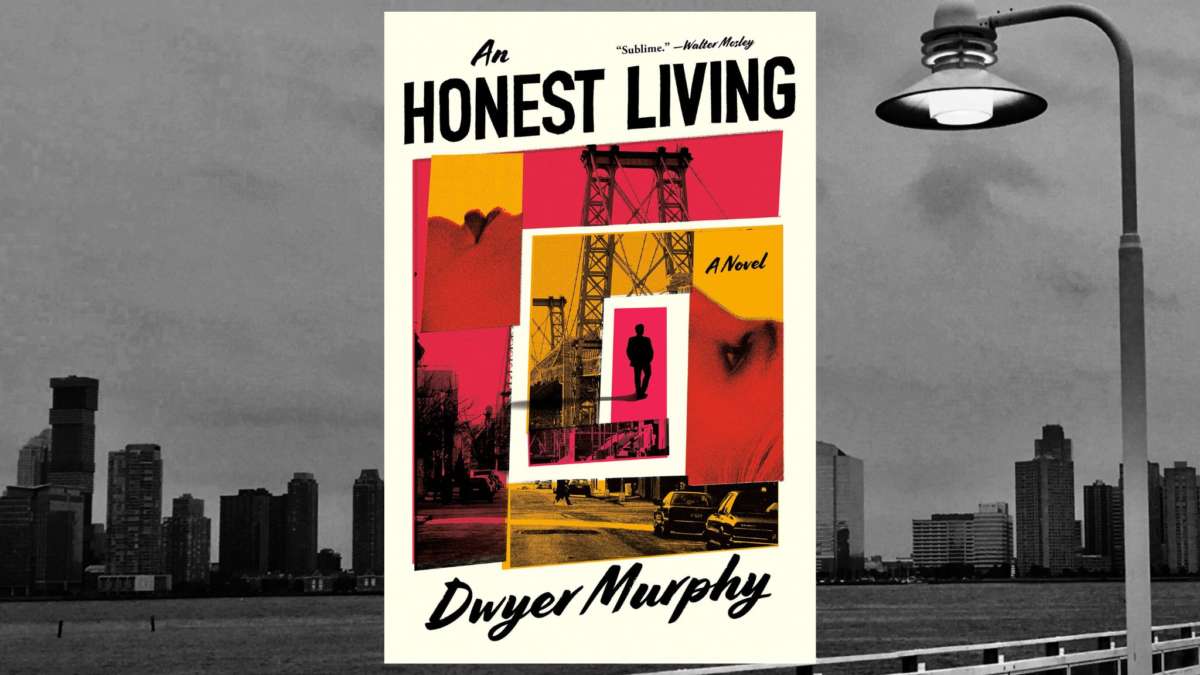

Some people find out about those consequences the hard way. The narrator of Dwyer Murphy’s An Honest Living (Viking) is one of them. A former big-firm lawyer, he’s now a private investigator in New York City, barely scratching out a living with odd jobs and small matters — neighborhood cases, petty disputes, document reviews, “trying to make a go of it on my own in a careless and not very profitable way.”

That ends when a woman named Anna Reddick walks into his life, offering him ten thousand dollars cash to find out what her husband is up to. It has nothing to do with infidelity. He’s a book dealer, and she’s sure he’s been selling things that belong to her. She just needs the proof: “Catch him at it, and you’ll get a bonus.”

Something about all this feels off, but, well, ten thousand dollars is a powerful incentive. Not as powerful as the consequences, though. Before he knows it, the detective is falling down a rabbit hole of conspiracies and grudges, a case filled with people bearing contradictory motives and destructive wishes. None more so than the second woman who lands on his doorstep that week. She’s the real Anna Reddick, and she has a few bones to pick with him …

An Honest Living is a novel about ambition and obsession, shadow and light, smoke and mirrors — a shimmering, often surprising, exploration of how fact and fiction reflect one another until the boundaries disappear.

“Go talk to people,” a friend tells him. “Shake things up. That’s what they always tell detectives to do.”

But they don’t tell you what to do when it ends up in the obituary pages …

REAL-LIFE INFLUENCES

Like his narrator, Dwyer Murphy used to be a lawyer for a big-time firm, and shares his character’s jaundiced view of the profession:

“It’s part and parcel of being a lawyer. Nobody takes a more cynical view of the profession than the practitioners themselves, although if you get them alone in a back booth toward the end of the evening, most of them will reveal a few closely guarded illusions. That’s the version of the profession I love. I’d say I’m probably a few degrees more jaundiced than my narrator, but not without a deep well of appreciation. I was never drawn so much to the Atticus Finch archetype, although that’s perfectly respectable. Give me Frank Galvin (Paul Newman’s character from The Verdict) or Saul Goodman any day. Lawyering is a genteel version of hustling in my view: a long con undergirded with a bold streak of self-doubt, equivocation and romance.”

Of his own cases, “the former lawyer in me requires me to be cryptic and overly discreet about the war stories, but I was closely involved in a dispute between two major financial institutions who both wanted to own the color black” — an incident reflected in the book. But, “that wasn’t nearly the strangest case. There were warring potato chip companies, philosophical gangsters, recession crusaders and oil family sagas out of a telenovela. And then there were the run-ins with WASP nudity rituals, which I also brought to the book. There’s a certain class of old New York power brokers and scions who feel safest in the confines of a locker room and will take any opportunity to lecture you while they (not you) are in the buff. Once that’s happened, how can you not write a novel?

CAPTURING THE ESSENCE OF CLASSIC MOVIES

“This novel started with Chinatown. My wife was pregnant with our first child and we would stay up late watching old movies and talking through what kind of obscure lawsuits the characters might have brought against one another. Just normal, everyday lawyer pillow talk. Chinatown got inside my head. I started seeing various prospective Jake Gittes and Evelyn Mulwrays all over the place, for reasons I still can’t fully explain, and from there it seemed the most ordinary thing in the world to write a screwball detective novel tied to that movie’s influence. And to a lot of other movies, as well.

“For me, New York has always been a city of bookshops and movie theaters. I spent most of my twenties tracking down friends to go see whatever was playing at The Film Forum, Sunshine, Angelika, Paris, and a few other favorites. At the main branch of the Brooklyn library, where I was living back then, I found out they had a collection, too, of every movie I had ever wanted to see and a thousand more I hadn’t known about, and they would give them to you for free, no questions asked, so long as you had a working card. I checked out something new almost every night while gorging myself on jerk chicken from The Islands on Washington Avenue. I couldn’t believe my luck, coming to a city like that. Keeping up with law school was a third or fourth priority. The only New York I wanted to live in was the one where on a given day you could catch an afternoon showing of Rear Window, then spend a few hours afterward at the diner talking through all your elaborate theories about what Thelma Ritter (Jimmy Stewart’s nurse) was really up to.”

“For me, New York has always been a city of bookshops and movie theaters. I spent most of my twenties tracking down friends to go see whatever was playing at The Film Forum, Sunshine, Angelika, Paris, and a few other favorites. At the main branch of the Brooklyn library, where I was living back then, I found out they had a collection, too, of every movie I had ever wanted to see and a thousand more I hadn’t known about, and they would give them to you for free, no questions asked, so long as you had a working card. I checked out something new almost every night while gorging myself on jerk chicken from The Islands on Washington Avenue. I couldn’t believe my luck, coming to a city like that. Keeping up with law school was a third or fourth priority. The only New York I wanted to live in was the one where on a given day you could catch an afternoon showing of Rear Window, then spend a few hours afterward at the diner talking through all your elaborate theories about what Thelma Ritter (Jimmy Stewart’s nurse) was really up to.”

The influence of some of those movies can be found in the book, not only Chinatown and Rear Window, but Touch of Evil, The French Connection, Roman Holiday, Three Days of the Condor. “The movies that worked their way into the novel were the ones that obsessed me for a time. The ones that obsess me still. Hanging around those movie theaters, getting that education, those were formative moments for me. And for some of my characters. It was this thing that bonded us and gave us a shared cultural memory to eulogize. Just to give you a particular example, my editor and I carefully plotted out the timing of the entire novel to make sure the characters could catch a showing of Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows at The Film Forum because there was this odd period in 2006 or so when it really felt like everyone you ran into was planning to catch a Melville show there or had just done it. That’s not strictly true, but sometimes New York distills itself down to these beautiful little communities of curious, big-hearted aficionados. We wanted to capture a piece of that. That feeling of what it was like around that time.

“More than any other I’ve been to, New York is a city of neighborhoods. That’s changing all the time, and the borders and characters are always in flux, but pretty much you can still spend a very enjoyable and interesting day walking through what feels like a dozen or a hundred distinct places, with some sense of history and culture and attitude to them. How can you write a New York novel without bringing that feeling to bear? In a lot of ways, I thought of this as a flâneur novel. A story about people who walk around looking for one another, or for nothing at all, just opening themselves up to the world. That dovetails nicely with the tradition of the private eye, who also hits the streets, talks to a lot of people, and gets spun around by fate. And of course, crime fiction has its own formidable tradition of bringing everything back to real estate. Who owns the buildings, the streets, who’s forcing someone out, who’s buying the water out from beneath you. If you’re interested in corruption and the true heart of noir, it’s in real estate.”

AN AUTHOR WHO KNOWS CRIME STORIES

Dwyer Murphy knows his crime fiction. He’s the editor-in-chief of CrimeReads, one of the preeminent mystery and suspense sites on the internet: “I get to spend my days completely absorbed in crime fiction. Educating myself on classics, and discovering all the incredible new talents out there today. There’s such a rich literary tradition there, so many offshoots, styles and experiments, there’s always something new to read or watch and pass along.

“I’m quite exposed in this regard — the influences are right there on the page since there’s this conceit that the books and movies we love permeate our everyday lives and shape our conception of the mysteries that surround us. So in that way, the short stories of Jorge Luis Borges factor in, as does Roberto Bolaño, who was in a way responding to Borges in so many of his novels. From the crime fiction world, Ross Macdonald and Margaret Millar — married, as you know — had a strong influence, which must explain some of the midcentury noir atmosphere. And like the narrator, I also have an abiding love of certain old novels with outsize ambition, which is why I named the first section of the book after a volume from Edith Wharton, who will, for me, always be the quintessential New York novelist. From more contemporary writers, I was looking constantly for guidance and tools to Walter Mosley, Megan Abbott, Idra Novey, Santiago Gamboa, Patrick Modiano, Patrick Hoffman, Javier Marias, Laura van den Berg and others. And then, always when I’m writing, there’s Elmore Leonard, or my own private Elmore Leonard, the one I’ve imagined, egging me on, urging me to remember one more bizarre detail from a conversation overheard years ago.”

The word “conversation” is key: “I tried to imagine I was telling someone this story. That sounds fairly simple but it was important for me to keep in mind. Not every page needed a revelation or even a point, necessarily, but it had to have some wit to it, something interesting — a line, an idea, a train of thought that would force that imaginary person sitting across from me in the booth to perk up and wonder. That, for me, is what makes old noir novels so great — that conversational style laced with unexpected moments of insight and loss.

“And like I said before, whenever I felt myself or the story or the language lagging, I liked to pretend Elmore Leonard was hanging around, judging me.”

LAWYER TURNS WRITER

Speaking of judging, with his background, what was it like to dip his toe into the novelist’s world himself? Was it easier or harder? As it turns out, a bit of both: “My agent, Duvall Osteen, had heard me read years ago, when I was an emerging writer fellow at the Center for Fiction. In the years that followed, I gave up on a lot of projects and thought about giving up on writing altogether, but then I would always run into someone from the New York book world and they would say, ‘Hey, Duvall told me you’re a good writer.’ That meant a lot to me and I always knew that if I actually ever got around to finishing a novel I would ask her to represent it. She agreed to, and she knew she wanted to give it to Ibrahim Ahmad, now my editor at Viking, who turned out to have been hanging around all the same New York bars and movie theaters and jerk chicken shops where I was hanging out in the mid-2000s, and who has the best, most interesting taste in books of anyone I’ve ever met. As we went through the editing process, he kept encouraging me to make the thing a little weirder, a little more personal. Maybe that’s why we have so many scenes where people are dancing in the background — no particular explanation needed or offered. Sometimes people just dance.”

Next up: “A sequel to An Honest Living, set in Miami, with a lot of characters running around talking about books and movies and dancing and occasionally somebody is killed or badly hurt and all of them dream of obscure lawsuits.”

Elmore Leonard would approve …

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Dwyer-Murphy-Author.jpeg

Photo Credit: Carolina Henriquez-Schmitz

About Dwyer Murphy:

Dwyer Murphy is a New York-based writer and editor. He is the editor-in-chief of CrimeReads, Literary Hub‘s crime fiction vertical and the world’s most popular destination for thriller readers. He practiced law at Debevoise & Plimpton in New York City, where he was a litigator, and served as editor of the Columbia Law Review. He was previously an Emerging Writer Fellow at the Center for Fiction. His writing has appeared in The Common, Rolling Stone, Guernica, The Paris Review Daily, Electric Literature and other publications.