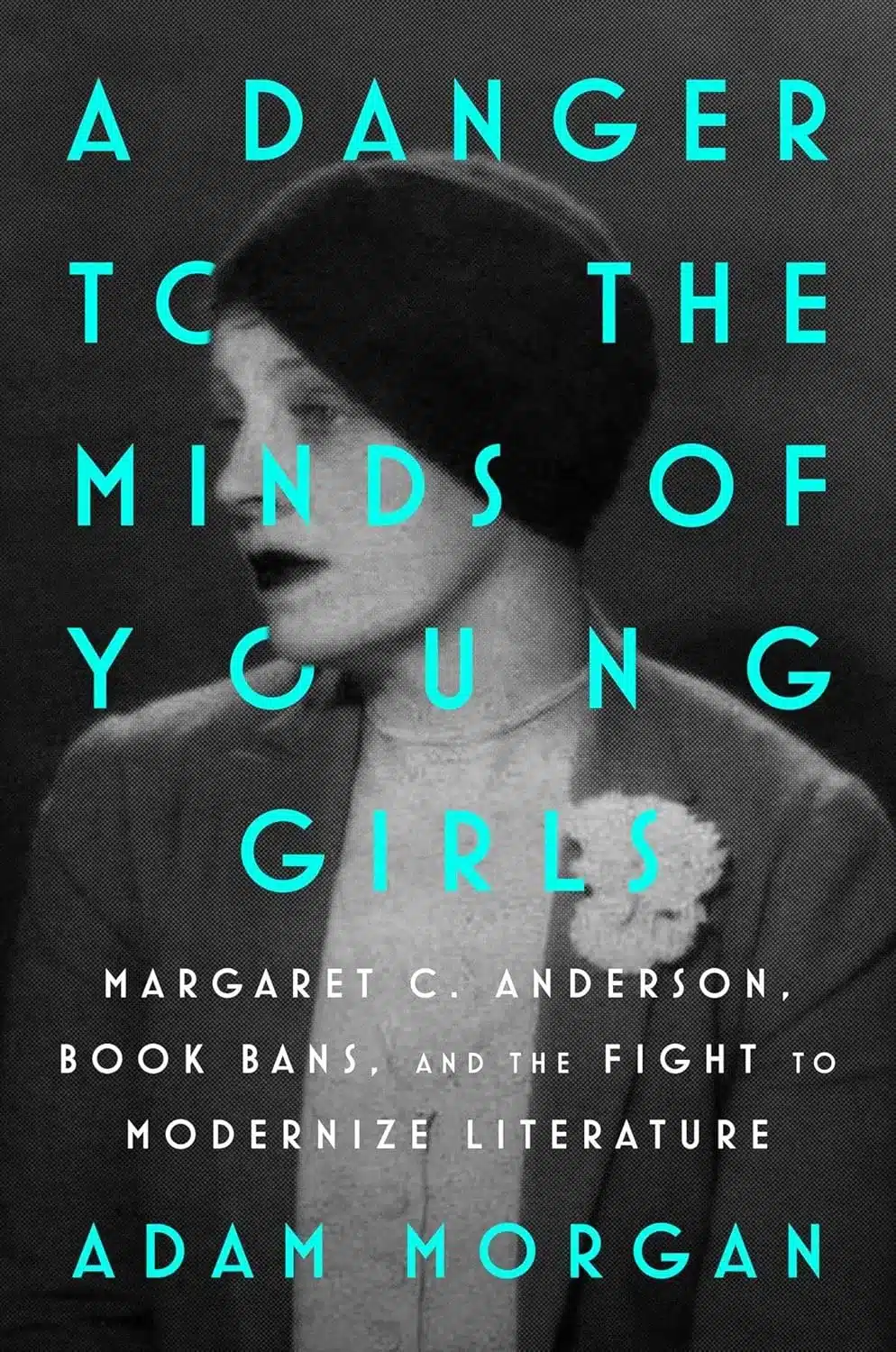

A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls: Margaret C. Anderson, Book Bans, and the Fight to Modernize Literature by Adam Morgan

A new biography of the bohemian powerhouse Margaret C. Anderson opens with a quotation from Anthony Comstock, who has been in the news recently, although he died over 100 years ago.

Comstock was a censorious bully who objected to the publication and distribution of written material that he deemed offensive. The Comstock Act, passed by Congress in 1873, once obtained to contraceptives, too. The laws remain part of the Federal Criminal Code and are potentially enforceable.

In 1918, Margaret Anderson ran headlong into the Comstock Act after she began the serialization of James Joyce’s novel, Ulysses, in her avant-garde literary journal, The Little Review. The U.S. Post Office’s seizure of that and subsequent issues led to an “obscenity trial” about “lewd” literature alleged to destroy the innocence of children.

Although Margaret and her publisher, Jane Heap, were convicted and fined, they did not serve time. Yet the trial may have been the indomitable editor’s greatest tribulation.

A Nation in Upheaval

These were difficult years in America, chillingly evoked by culture critic Adam Morgan in A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls: Margaret C. Anderson, Book Bans, and the Fight to Modernize Literature. The story of Anderson and her colleagues and friends, especially in Chicago and New York City, is set against the backdrop of the 1920s Red Scare and the specter of anarchism.

The 1920 Federal Census was the first to show that the U.S. population had shifted from rural to urban. Radio transformed entertainment and consumerism. Newspapers and magazines popularized new manners, ideas and art. Inevitably, modern culture provoked a reactionary response from the government and conservatives. Margaret Anderson and many writers and artists were swept into the fray.

Beautiful and imaginative, Margaret once quipped, “I always edit everything.” One thing she did not put the brakes on was her far-flung life, remaining unfazed by the judgment of others.

A Rebellious Mind Awakening

The eldest daughter of a business executive and his fearful, repressive wife, Margaret seems to have been born rebellious. Growing up in the conservative Midwest, she tuned out by listening to music and reading in the attic. Her mother disapproved of her choices: Shelley, Keats, Dostoyevsky and Havelock Ellis — an English physician who wrote about human sexuality.

“We don’t know exactly when Margaret realized she was queer,” writes Morgan. He suggests that Margaret may have discovered herself during childhood doll-playing with her sisters when she pretended to be a man who conquered “fatal women.”

The family moved around Ohio and Indiana while Margaret fervently hoped to escape the household’s smothering Victorianism. Unexpectedly, in 1908, the editor Clara Laughlin invited her to spend the summer in Chicago. At last, 22-year-old Margaret would meet the world!

Under Clara’s wing, she attended the symphony, explored Michigan Avenue and discovered Browne’s Bookstore, whose proprietor — Francis Fisher Browne — was the editor of a famous literary review, The Dial. Within a year, Browne hired Margaret as his chief assistant. At its office in the Fine Arts Building, which also housed Poetry: a Magazine of Verse, Margaret became friends with the likes of critic Harriet Monroe, sculptor Lorado Taft and author Hamlin Garland.

Here in the 21st century, these names have faded from collective memory. Yet once upon a time such artists and writers, along with editor Floyd Dell, poet Carl Sandburg, authors Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson, and reporter Ben Hecht (brimming with unrequited love for Margaret, he would become an Oscar-winning screenwriter) formed the core of an influential salon based in the South Side neighborhood of Hyde Park, where the University of Chicago would become an intellectual epicenter.

The Fire of Modernism

Margaret’s days grew busier as she began work as a book critic for the Chicago Evening Post and made plans to launch The Little Review. Aligning herself with the anarchist Emma Goldman and labor leader Big Bill Haywood, she caught the interest of the Bureau of Investigation (forerunner to the FBI).

Margaret’s parents moved to Chicago, and she grew close to her father. But after his death in 1914, she became permanently estranged from her mother.

The next year, after The Little Review made its debut, Margaret fell deeply in love with the artist Jane Heap, who became publisher of the Review. In 1917, just as the U.S. entered World War I, they moved to New York City and were welcomed into a bohemian, antiwar circle that included the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, Masses editor Max Eastman, writer John Reed and playwright Eugene O’Neill.

In their small Greenwich Village apartment, Margaret and Jane struggled to get by. The Little Review drew criticism as well as accolades, and its readership fluctuated. Following a bare-bones Christmas, the two women needed a glimmer of hope. In late January of 1918, hope arrived in the mail: the first chapter of Ulysses sent from London by the poet Ezra Pound. There was no doubt in Margaret’s mind that she would publish it.

Three years later, Margaret and Jane sat in court while John Quinn — a New York attorney with a passion for modern art — defended them against charges of violating obscenity laws. In fact, Quinn didn’t think much of the case. “You’re idiots, both of you,” he told the women. “You’re damned fools trying to get away with publishing Ulysses in this Puritan-ridden country.”

Margaret emerged from the trial rattled and disgusted. Although she lived 86 years of romance, spirituality and adventure, the 1921 verdict against free speech was a defining moment in her life. Readers will be astonished that the arguments on both sides resonate in our own time.

About Adam Morgan: