At the risk of sounding glib, it seems you can’t turn your head these days without alighting on a celebrity memoir — and that in all likelihood, its pages will be stuffed to the margins with trauma.

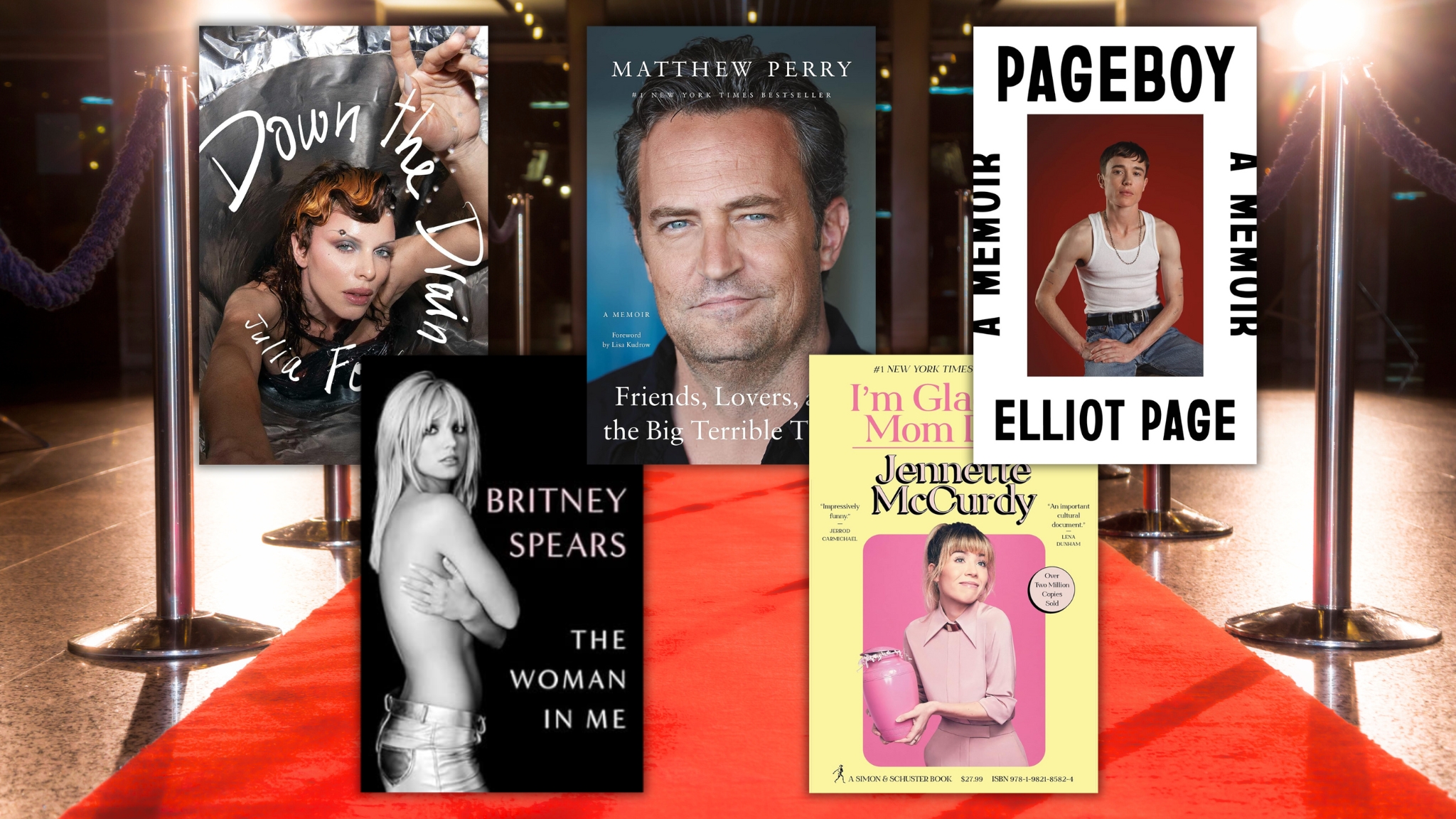

In the last two years, there’s been a veritable explosion of celebrity memoirs hinging on the traumatic upbringings, breakthroughs and adult lives of their subjects. The starting pistol rang out in summer 2022 with Jennette McCurdy’s viscerally unforgettable tell-all I’m Glad My Mom Died; since then, other celebrity “trauma titles” have included memoirs from Britney Spears, Matthew Perry, Julia Fox and Elliot Page.

And while these memoirs vary in their alleged contributions from ghostwriters — McCurdy, Fox and Page, for example, all insist they did the work themselves — one thing is certain: past trauma plus painstaking description (emphasis on the pain) seems to be today’s formula for celebrity memoir success.

But should it be? In my own consumption of these works, I’ve detected not only an eerily similar narrative focus, but also some fairly fraught implications about modern culture, not to mention an alarming message to writers about what it really takes to sell a book. It seems entirely possible that such memoirs may not be serving a net good — and that their prevalence is negatively impacting readers and writers alike.

So what have been the positive outcomes of such celebrity memoirs, if any, and what can the rest of us gather from their exceptional popularity?

An era of radical honesty

Let’s start with the cultural upside: while these trauma-filled stories are certainly upsetting to read, they do indicate a positive cultural shift toward the acceptability of talking about trauma. As little as a decade ago, similar stories — even from celebrities — would have been met with derision and ignorance from both higher-ups and the general public.

But the spark that began with #MeToo, along with similar social justice movements of the 2010s, has been fanned into a flame of greatly increased openness and accountability. For the most part, this is a good thing; gone are the days of Hollywood producers and C-suite execs being able to harass women with reckless impunity. So, too, have many other societal wrongs been somewhat (if not entirely) ameliorated by people speaking out against racism, sexism, ableism, and other forms of prejudice and abuse in both systemic and personal contexts.

And celebrities, powerful as we may perceive them, have never been immune to such abuses. In fact, the opposite seems to be true: they have been exponentially more exposed to toxic people and environments in the entertainment business than the rest of us.

In their memoirs, this might take the form of a nightmarish, eating-disorder-inducing stage parent (McCurdy’s mother); a controlling boyfriend who insists on a secret abortion (Spears’ past boyfriend Justin Timberlake); or a culture of drug and alcohol use that leads to a lifelong battle with addiction (Matthew Perry’s experience on Friends). Wherever you go, there you are, it seems — if you is a celebrity, and there is a setting of horrific, practically inevitable trauma.

There’s no doubt in my mind that these celebrities deserve to tell their stories as they see fit, and that the individuals they hold accountable deserve our censure. Yet I can’t help wondering: would they have produced memoirs in the first place if they weren’t assured of their work being profitable? If now were not such a culturally convenient time to capitalize on trauma, would these books even exist?

Of course, we are all only products of our time, including (and in many ways especially) celebrities. But these initial thoughts about profitability lead to more deeply troubling questions about the relative “value” of different trauma stories.

Not all trauma is created equal

You’d have to be living under a rock not to have heard snippets from at least one of the above titles in recent months. Anecdotes from McCurdy’s, Perry’s and Spears’ memoirs have all made extensive rounds on social media; I remember one week when I couldn’t scroll for thirty seconds without encountering another clip of Michelle Williams narrating The Woman in Me.

And with each of these three titles boasting well over 250,000 Goodreads star ratings — McCurdy’s now approaches one million — it’s clear they have succeeded, if nothing else, in garnering quite a bit of (again, well deserved!) attention and sympathy.

However, not all recent celebrity memoirs have been so successful. A few more relevant celebrity titles released since 2022 have been Viola Davis’s Finding Me, Constance Wu’s Making A Scene, and Jada Pinkett Smith’s Worthy. None of these books have been devoid of significant trauma, ranging from Davis’s childhood in extreme poverty to Wu’s experience of sexual assault on the set of Fresh Off the Boat. Yet for some reason, their stories did not reach nearly the same frenzied heights of social media exposure, or indeed of pure readership, as the aforementioned titles.

This has been particularly true for Wu and Pinkett Smith. While arguably less notable than EGOT winner Viola Davis, the fame gap still doesn’t explain how each of their books has fewer than 10,000 star ratings on Goodreads. Jennette McCurdy was as famous, if not much less so, as Wu and Pinkett Smith when she released her memoir in August 2022; how can it be that I’m Glad My Mom Died has accrued nearly 100x the number of ratings that Making a Scene and Worthy have respectively?

The first hypothesis is obvious, if quite disheartening: that the sheer relentlessness of trauma in McCurdy’s memoir makes for a more gripping read than Wu’s or Pinkett Smith’s. McCurdy jumps from her dysfunctional upbringing to abuse on the iCarly set to her devastating eating disorder, with barely a line to catch one’s breath. It might sound exceptionally cynical, but in terms of quantity and variety of trauma, McCurdy beats the other celebrities by a mile.

Another hypothesis, and one which I think has a good amount of supporting evidence, is this: that as readers, as social media participants, and as a society, we do not find the stories of women of color to be as interesting or valuable as those of white women. We see this pattern take many forms, of course — in the popularity of white-led books and TV shows, in the more sinister context of medical gaslighting — but I’ve personally been shocked by the chasm that’s apparent in celebrity memoirs as well.

The major exception to this hypothesis would be Michelle Obama’s phenomenally bestselling 2018 memoir Becoming… but critically, Becoming is a memoir that’s low on trauma, high on hope. Even if we don’t unilaterally devalue the stories of celebrity WoC compared to white celebrities, I do think this data point speaks to what we tend to expect (and ultimately prefer) in the stories of WoC: persistence, optimism and gratitude rather than raw honesty and trauma.

All that said, it’s hard to identify any single component which makes one celebrity memoir more successful than another. But even if we can’t be sure of the root cause(s), the takeaway is the same: all trauma is not created equal, even among celebrities.

And when we dive into the implications for non-celebrities, the divide becomes even more drastic.

The perils for non-celebrity imitators

If you’ve spent much time on TikTok lately, you’ll know that trauma narratives — whether played for laughs or genuinely wrenching — are not celebrity-exclusive commodities. Celebs may have helped movements like #MeToo get off the ground, but the wider trend of trauma-sharing has largely been proliferated by civilians on social media.

Consequently, it’s not surprising that as celebrity memoirs have increasingly focused on trauma, a vicious cycle has emerged wherein “normies” are even more encouraged to air their own — and to capitalize on it through TikTok, podcasts, and even their own tell-all memoirs.

The problem with this is not only that non-celebrity memoirists are unlikely to reach the same levels of success, but also that if they do gain any unwelcome exposure, they won’t be able to fall back on their existing resources like most celebrities can. Civilians may see these celebrity memoirs topping the bestseller lists and think, Hey, I’ve had some interesting trauma. I can do that, too! But regular people seem poised to eventually regret exposing their lives so publicly — and they won’t have the money, legal assets, or powerful friends that would soften the blow for a similarly regretful celebrity.

It’s also worth noting that even celebrity memoirists who are tremendously successful might still wish, someday, that they hadn’t revealed quite so much. While reading I’m Glad My Mom Died, I was repeatedly struck by how much of McCurdy’s trauma scanned not just as tragic, but humiliatingly so — how it read more like her private journal, or like a therapy transcript, than it did a polished and traditionally published book. If it had been written by a biographer rather than (again, supposedly) McCurdy herself, it would have felt overwhelmingly exploitative.

Of course, it’s possible this was intentional: a strategically intimate style designed to entice readers and sell more books. But given how little introspection there is throughout IGMMD — and how McCurdy only starts seeing an actual therapist at the tail end of the memoir — I can’t help but wonder how her future self might feel, about this very public record of her very lowest moments. If it could potentially be so bad for her (and Spears, and Page, and all the rest of them), it would only be worse for non-celebrities in the same boat.

Do these books ultimately help us?

Despite my cynicism around capitalism-driven narratives, the cultural values assigned to different kinds of trauma, and indeed about its writers’ possible regrets, I don’t think these trauma memoirs are inherently unhelpful.

Many an average person has seen their own struggles mirrored in a celebrity memoir, and even I would not underestimate the cathartic and practical effects of this. Also, when read with care, such stories can greatly increase people’s sympathy for issues outside their own experience — and this broadening of emotional horizons can touch the lives of many more.

That said, I do strongly feel that we would all benefit from more reflection around these kinds of trauma narratives and why we find them so compelling. It’s human nature to be curious, and similarly, to commiserate with one another over life’s challenges — but we must strive to keep that same humanity intact, to not simply grasp for ever-increasing personal trauma to feed our impatient brains.

We can do this by always considering these stories in a cultural context; by searching for patterns of presentation and consumption; and by remembering that behind each memoir — no matter how famous the face on its cover — is a real, deeply feeling person.

If we can achieve these things, perhaps there’s hope for the celebrity trauma memoir after all.