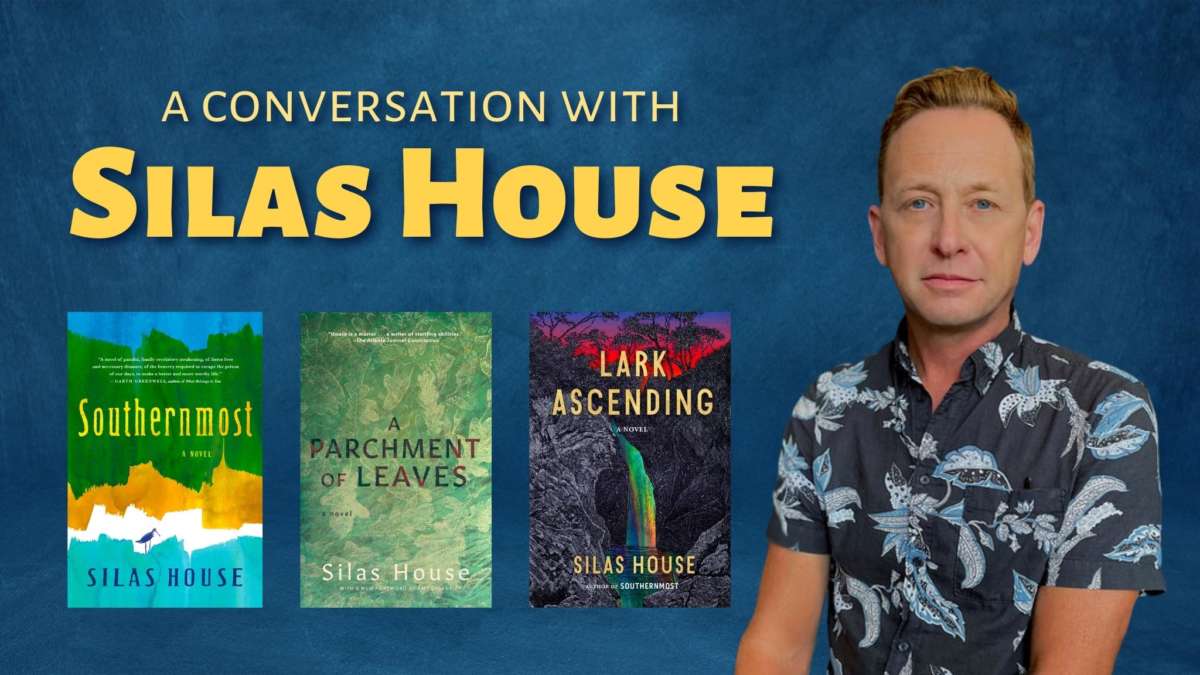

BookTrib is proud to share this previously unpublished conversational interview with Silas House. Silas House is the a bestselling and award-winning author of several novels, a handful of plays and one book of creative nonfiction.

The following interview was conducted in November of 2013 by Linda Hitchcock, a frequent BookTrib contributor.

INTERVIEW WITH SILAS HOUSE

LKH: Were your parents and family readers?

SH: They were not. My parents encouraged my reading but my cousins teased me about it. I grew up in a very fundamentalist, Pentecostal family who were constant readers of The Bible.

I grew up in a small, close-knit, complicated community. In a one-mile stretch lived several cousins with more family two counties away and frequent visiting. It was both wonderful and awful to have family so close. It was smothering and hemmed in. I was the only one who was different. My cousins watched wrestling while I liked Tennessee Williams.

The (Laurel) County Library restricted children to children’s section until about age 12. I got most books from yard sales and flea markets. I never read a book without getting something out of it. I learned plotting and themes, to use one thesis per book.

LKH: What books influenced you most growing up?

SH: To Kill a Mockingbird read in 7th grade was most influential. I imitated the writing initially until I found my own voice. S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders made its way into Same Sun Here as the pen pals from different backgrounds read it. My Antonia by Willa Cather and Conrad Richter’s Light in the Forest which aren’t read much anymore.

I spent a lot of time with my aunt and read the two books she had on her dresser, aside from The Bible: Gone With the Wind and Peyton Place. I don’t think she read them but she owned them because she loved the movies.

We watched Tennessee Williams films and William Inge’s Come Back Little Sheba on TV together and I read a lot of plays. Peyton Place was well written with nature, imagery, and exposed hypocrisy. Potboilers today are not well written.

LKH: What was it like for you to attend the small, now defunct college, Sue Bennett College?

SH: It was only seven miles from home but a world apart. Sue Bennett College was Methodist with only 500 students so you knew everybody.

Learning that church was about to be in service changed me in a profound way. It changed my religiosity. My first three books were formed by searching for what I believed in or to find the way of my faith. We always need to think of ways to be in service.

LKH: Like storytelling singer/songwriter John Prine who began his career as a rural mail carrier, what was this job like for you?

SH: I worked seven years as a rural mail carrier and learned so much about humanity; the best and the worst about people. It was a meditative job where I would glance at the first three letters of a name, throw letters in the box and think about a scene I was going to write.

It was a great time of stillness. I’d finish the day and go home and write. Unlike many writers who require quiet, I thrive on noise; on chaos. For the first seven years, I wrote with a young’un on my knee. I always write to music specifically selected for each book. (Playlists are available on Spotify.)

Near the end of my carrying the mail I delivered a parcel to a woman on my route and she happened to be at the mailbox and she said “That’s your book. Open it and sign it for me.” So that’s full circle from writing it on the mail route to actually signing it at the mailbox. I quit the mail shortly after that. Thank the Lord.

LKH: What was your first published piece?

SH: The first published piece was after the Olympic Torch came through along Hwy 25 in 1996 and I wrote about how it brought the community together for the regional paper. I was paid $5. I cashed the check but made a copy and still have it. It was my first payment for writing.

LKH: What are some of the influences for your writing?

SH: My first three books are largely informed by a search for what I believe in; trying to find my way of faith and finding a congregation to match that. I feel like my next three books, Eli the Good, Same Sun Here, and my new book are the real social justice-driven books. They’re all about being of service and finding ways to do that with different definitions for being of service. Being a soldier is being of service and so is being a schoolteacher or being an artist and so on.

LKH: What to you is the difference between a wordsmith and a writer?

SH: I would probably think of it more in the way of a difference between a writer and a storyteller. “The most important thing is to make a sentence sing.

I think that a writer is language driven above all else and a storyteller is story driven above all else. A writer must be worried about language and story. You want to make your reader feel emotions.

If you think about a piece of literary fiction versus a piece of commercial fiction: a literary novel should entertain and do more; it should leave you with some ambiguity and you should be questioning things and learn something from it. Whereas a commercial novel, for the most part, is just entertainment. Sometimes I just want a beach read, you know?

LKH: What is it about Southern Appalachian literature that sets it apart?

SH: I think it is sense of place and I think we’re at a particular time when sense of place is more important than ever because America is becoming so homogenized. You drive into Milwaukee and it will be the same as driving into Bowling Green because it’s going to be the same strip of chains whereas fifty years ago that wouldn’t be the case.

In my hometown, the little community store where there was a mixing of generations visiting has been replaced by a Chevron. When it comes right down to it any really good writer has a real sense of place.

Rural and working class people are to me sort of the same thing as Kentucky. That’s the way I think of Kentucky, my Kentucky and I know that’s not everybody’s Kentucky, but my Kentucky is a rural place, it’s a green place; a working class place, that’s the way I think about it.

LKH: Who were your most influential mentors?

SH: Lee Smith, for sure. In eighth grade I read her book Black Mountain Breakdown and it was the first time I realized I could write about my people. Before that I was setting everything in a much deeper South than I was from.

Lee was my primary mentor who taught me so much, not only about writing, but also about how to be a writer, and how to protect my writing time, how to seek out stillness, and how to act on the road; how to be on book tour. To always, no matter how hard it got, to remember that those people had gotten ready and come out to see you and had chosen to spend two hours of their day with you and to always be conscious of that. I always leave a reading or an event feeling like I haven’t given enough.

Robert Morgan, who wrote Gap Creek, was hugely generous to me. I was put on book tour with him because we had the same publisher. I had not been anywhere, had not done anything and a few weeks after we started our book tour together Oprah chose his book.

So we went from having twenty people at a reading to several thousand. He made sure that I was given equal time in those readings. He never made it about him, even though everybody was there to see him and it introduced me to thousands of readers.

LKH: What do you enjoy reading?

SH: I primarily read fiction and nonfiction for research. When I’m writing a novel, which I have always been for years, I have to be really selective in what I’m reading. I want to read something that’s very different from the voice I’m writing in.

LKH: What lessons are your books teaching you?

SH: I tell people all the time that I think for me and for most writers I know when you write a book you’re writing it to learn something from it, to answer questions for yourself.

The thing I keep coming back to is that ultimately everything goes back to the Golden Rule. Everything. When you’re writing about characters and human beings it always comes back to that. Is this character trying their best to live by the Golden Rule or are they trying their best to defy it. So I think literature helps us to be better people because ultimately every story is about good versus evil. Always.

So I think writing for me is a prayerful thing, it allows me to go into a prayerful place, a meditative place, in a way that nothing else allows me to. And I think I also learn that human beings are endlessly fascinating. You could write a good book about somebody sitting in a hotel room. The plot really doesn’t matter as much as the character. If you don’t have a good character, even if the character is a dog, it’s all about character.

LKH: Could you tell me a little about your playwriting?

SH: All of my plays have been commissioned so it’s a different thing for me. I still really hesitate to call myself a playwright; I totally identify as a novelist. I always feel like a bit of a phony to call myself a playwright. For me, plays teach me a lot about being a better writer. I think that it’s a much harder form, for me, writing a play or a poem.

LKH: How long does it take you to write a novel from inspiration to sending the baby off?

SH: It depends. I wrote A Parchment of Leaves in just a couple of years. I felt that it was being whispered to me. I thought about Eli the Good for about fifteen years. So from first thinking about it to being published was about fifteen years. Same Sun Here we wrote over the course of a school year because we wrote it in real-time. (Written with Neela Vaswani)

LKH: How to you manage your time?

SH: You have to think of yourself as a juggler and you have to pay very close attention to your calendar and I fail a lot at managing it properly. The hardest part is guarding my writing time.

LKH: What are your thoughts on the importance of awards to authors?

SH: I don’t want to dismiss awards but at the same time I don’t put that much stock in them. They’re always nice to get, but, ultimately I think to me it’s more important for a reader to write me a letter or to come to my reading and say this book had a profound impact on me. That touches me much more deeply.

I’ve had two books that sort of wrote themselves and both of those books were the ones that won the most awards for me. I think sometimes the more organic a book is the more acclaimed it becomes. The less an author is visible in it the more able readers are to connect to it.

LKH: I guess the last question really is what questions do interviewers fail to ask you?

SH: They always fail to ask about the religious aspects of my work and I think that’s because we don’t talk about that much in our mainstream media. I guess the main thing that most people ask me about are things like stereotypes and I end up talking a lot more about Appalachian culture than I do my books. I like to talk about thematic elements in a book. That’s really important to me.

For me, Parchment of Leaves is all about forgiveness. Clay’s Quilt is all about storytelling. The Coal Tattoo is about family which seems kind of generic but I tend to think that water is thicker than blood in a lot of ways in that blood’s thicker than water thing is an illusion to some degree. Family is about family. It’s not about necessarily who you’re kin to as much as who is good to you.

Same Sun Here is about friendship in different cultures. Eli the Good is about freedom and the responsibility of having freedom. When I write a book I have that theme above my writing table. It’s always there, I’m always looking at it and every sentence has to report back to that.

SOME AUDIENCE QUESTIONS

LKH: Note: The following excerpts are taken from the August 30, 2018 author talk/launch at Warren County Public Library in Bowling Green, KY for Southernmost, Silas shared “Southernmost’s thesis was inspired by Thomas Merton that everything is holy.” He also told us this novel was at the publishers in 2015 when he pulled it back and rewrote it. The finished book was the twelfth draft!

Would you describe your writing process and do you write in longhand?

SH: I use a laptop. I always write outside as much as the weather will permit me to. Right up until late October I’m on the porch and I’m out there at the end of March. When I’m not on the porch, I just write at the supper table. I don’t have an enclosed office. I don’t like to be in a small space when I write.

How long does it take for you to write a book and do you know the outcome?

SH: I usually spend at least five or six or seven years on a novel and I think that if I knew everything that was going to happen I don’t know if I could stick with it that long. It sort of keeps me going to figure out what’s going to happen.

About Silas House:

Silas House is the nationally bestselling author of several novels, a book of creative nonfiction and three plays. He is a former commentator for NPR’s “All Things Considered”. His writing has appeared recently in Time, The Atlantic, Ecotone, The Advocate, Garden and Gun, and Oxford American.

House serves on the fiction faculty at the Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Creative Writing and as the NEH Chair at Berea College.

He is a member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers, the recipient of three honorary doctorates, and is the winner of several awards.

House was an executive producer and a subject in the documentary Hillbilly (available on Hulu), which won awards from the Los Angeles Film Festival and the Foreign Press Association. As a music journalist, he has worked with artists such as Kacey Musgraves, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Jason Isbell, Senora May, Leann Womack, Charley Crockett and John R. Miller. House is also host of the popular podcast “On the Porch“. Find out more here.