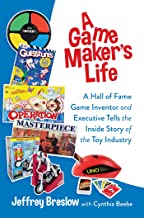

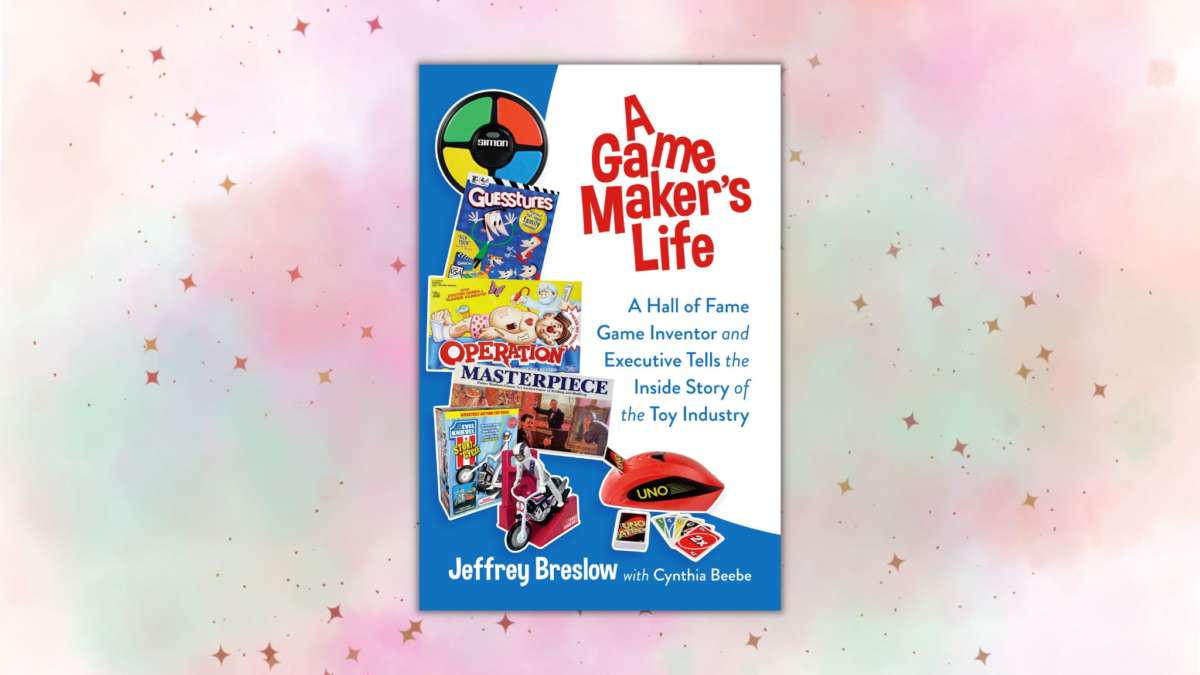

A Game Maker’s Life by Jeffrey Breslow

Jeffrey Breslow was an icon in the toy design business. In his 40-year, Hall of Fame career, he oversaw operations at two multimillion-dollar toy companies and had his hand in such classic toys at Simon, Polly Pocket, Operation, Mousetrap and more. His stories of late nights at the drawing board where ideas and strategies unfolded are memorable.

Yet two minutes on July 27, 1976, changed the entire narrative.

Breslow remembers in the prologue of his book A Game Maker’s Life, “I wouldn’t usually leave a meeting, but that morning I decided to take the phone call in another room. I stepped out through Anson’s back door and walked a few steps down the hall into an empty executive’s office. If I hadn’t moved to a different office to take Jim’s call, I would have been murdered.”

A FASCINATING AND NOTEWORTHY LIFE

It’s hard to process that a life devoted to providing fun, entertainment and learning for children was marked by such a horrific event. Top executives of the Marvin Glass & Associates industrial toy design company – a leader in its field – were gathered for their morning meeting in an executive conference room. The building was like a fortress – security was crucial for protecting projects in progress. So it was baffling that when Breslow stepped out of the room to take a call, a longtime company employee, a relatively quiet electrical engineer, walked through the back door and into the room with the executives and, with two guns, shot and killed three people.

As a reviewer, I was torn over whether to emphasize the killings over Breslow’s fascinating and noteworthy life behind many of the household-name toys and games with which our families grew up. But the fact that the tragedy is the very first anecdote Breslow delivers was enough to give it its proper attention. I mean, when you think about it, how could you not?

Not to be lost is the story of a person who from a very young age was obsessed with how things worked, to the point of tearing apart everyday products to understand their design and functionality. This curiosity served him well as he entered the world of industrial toy design. Not only did his projects need a natural hook to attract children, they had to be cost-effective from a production standpoint, and require no assembly or complicated instructions.

Breslow recalls vividly his early days with Marvin Glass, the charismatic founder of MGA, a genius, legend and primary mentor to the author. Through Glass, Breslow learned the tricks of the trade, the art of the presentation, and the dos and don’ts in life, in creating toys and in running a business.

SPRINKLED WITH LIFE LESSONS

In the end, he learned that being successful required the right combination of skill and luck.

After the office devastation that framed his life, Breslow and the company were able to survive, and get up off the mat and continue to be successful. He also found success establishing a second company, and later shifted to a life as a sculptor.

His story is a story well told, along with co-author Cynthia Beebe, sprinkled with anecdotes of creating some of the world’s iconic toys — and life lessons garnered from doing so.

In the book’s Afterword, Edward J. Zagorski, an industrial design professor and another of Breslow’s mentors, writes, “Jeffrey thinks clearly, leading to thinking independently. Thinking independently leads to thinking confidently and living confidently leads to living courageously. Living courageously leads to living hopefully.”

That is the essence of this game maker’s life.

About Jeffrey Breslow:

Jeffrey Breslow, a preeminent toy and game inventor and designer, spent more than 41 years inventing toys and games since graduating with a BFA from the University of Illinois in industrial design. In 1976 at the age of 34, he became the youngest managing partner of Marvin Glass and Associates, the leading toy design company in the world. Glass and Associates created games such as Simon, Operation, Guesstures, the Evel Knievel Motorcycle, Mousetrap, and UNO Attack! Breslow was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in New York City in 1988 and left the toy business in 2008 to sculpt full time. His sculptures are on display at the University of Illinois and the Lurie Children’s Hospital and on permanent display in Vermont, California, New Jersey, and Uruguay.