I’m not sure what I like more about the author Stanislas M. Yassukovich — the keen insights he has about people and situations, or the words he chooses to convey them.

This is the third chance we’ve gotten to review one of his works. First it was the novel James Grant, a granular look into the world of society’s upper class where pain often trumps privilege. Then it was his collection of short stories, aptly named Short Stories, which extended the theme of the jet-setting elite and added a dash of nostalgia to his narrative.

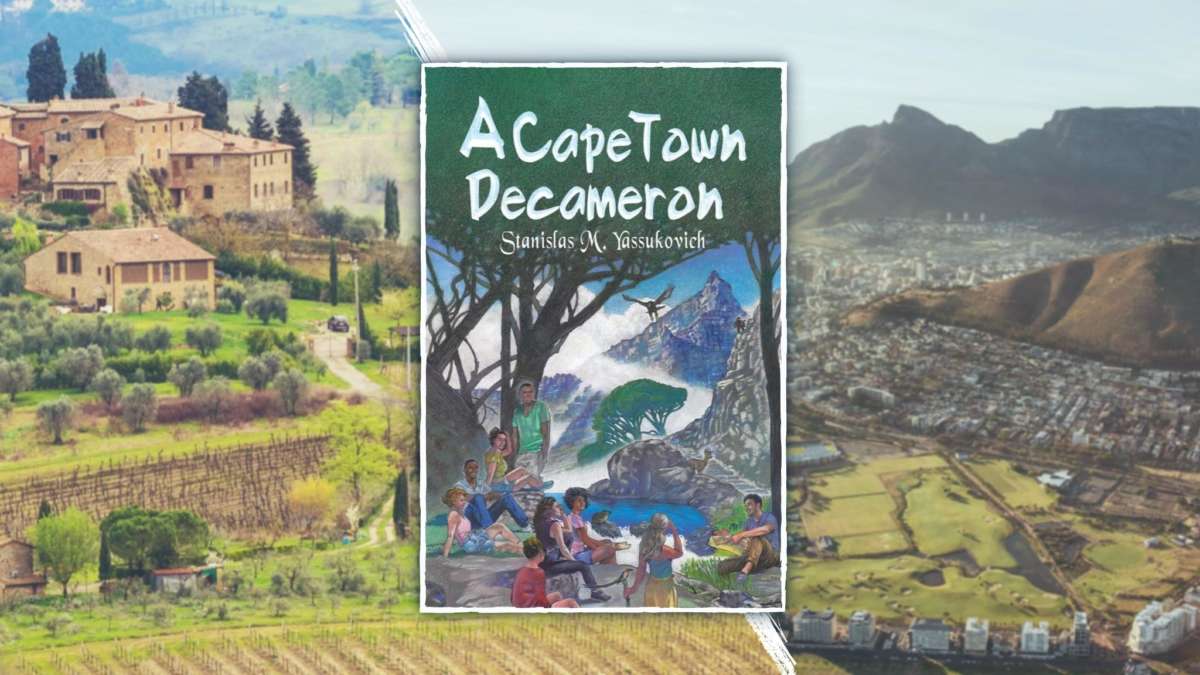

Now in A Cape Town Decameron (Austin Macauley Publishers ), Yassukovich offers up a new set of short stories, notable as much for the why and how behind them as the marvelous stories themselves. The author explains that back in 1354 when people in Florence were fleeing from the plague and seeking safety in an isolated Tuscan countryside, the poet and writer Giovanni Boccaccio used the solace and setting to write a series of tales that was later published as The Decameron.

Yassukovich replicates the concept as his forced isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic places him in a similar atmosphere conducive to writing and reflecting — which he does so well in the form of independent tales that explore the character, conscience and curiosity in people.

PROFOUND TALES OF HUMANITY

Some of the stories play up the theme of irony, in which he juxtaposes his leading cast members with contrasting traits, only to provide the ultimate twist at the end. This is the case in the story “No Fit — No Game,” in which Jasper Jakes is a creature of habit and, on the surface, hardly suited to the flighty, eccentric and unpredictable Veronica Veryfair, who eventually becomes his wife. Jakes describes himself as “the harbor in a storm” and she as “the raging sea.”

The author also introduces ironic twists in “Resurrection,” in which the narrator stumbles upon an old Harvard classmate working in a Florida supermarket helping people drag groceries to their parked cars. The employee was the victim of a Ponzi scheme, losing all his money and his sympathetic wife in the process. It was her feeling of pity that ultimately doomed their relationship. File that information!

And how about the financial whiz Harry Gubbins in “Noblesse Oblige,” whose shady dealings lead to a split with his partner. Shortly thereafter, fortunes turn, making for an interesting reunion.

Yassukovich treats us to a tale of intrigue, and more irony, in “The Clockmaker,” in which a small shop owner is presented with an offer to purchase an old clock from an admired customer who apparently does not realize the piece’s value. The shop owner has to decide whether to take advantage of the situation or come clean. The matter of conscience — to have one or not — has its consequences.

The story “House” is very different — but dazzling. The narrator rents a house to seek refuge as the world struggles with the spread of Covid-19. Is this the author himself describing his concept of escaping to a remote location to write his stories? Something strange happens during his stay, beyond imagination and disrupting the narrator’s intentions. But listen to this gifted writer describe his setting before chaos ensues: “No greater proof could exist of the nefarious consequences of industrialization than the blackened verdure and stunted growth of nature’s treasures, which covered the countryside like a veil of greasy gossamer … but for the echo of past frivolities, parks and fields which had once resounded to the cry of hounds, and now bore the crusted scars of mass residential development. But this environment of civilized decay, so typical of man’s twisted urge to foul his own nest, rather suited my literary intentions.”

WALKING THE LINE BETWEEN SWEET AND SOUR

Yassukovich observes continuously in his writing the connection between comedy and tragedy. In one instance, one of his protagonists utters, “The term tragicomic is highly suggestive. I felt I might be on the edge of a comic cliff looking over a tragic ravine.”

Judging an author’s work is so subjective. Outside of spell checks and dotting the I’s, what rules are there, really? Only rules of the imagination that have no boundaries. It’s all about taste — is it too sweet, too tart, or just the right seasoning for one’s liking. An old friend called me yesterday to tell me about “the best book I have ever read in my life.” Know for sure that that type of word of mouth goes a long way.

Whatever sort of “word of mouth” or subjective assessment one takes from this review and this reviewer (if you are at all familiar with my tastes and the wavelengths I so desperately cherish when I am on the same one as an author), this book and this author are my reading joy. Once again, in A Cape Town Decameron, Stanislas Yassukovich brings intelligence, insight, intrigue and strength of the written word to every passage.

If you marvel at language used wisely and melodically, and treasure good tales, be sure to add this collection to your TBR list as soon as you can.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/SMY_headshot.jpg

About Stanislas M. Yassukovich:

Stanislas M. Yassukovich was born in Paris to a Russian émigré father and a French mother. After being educated in the United States, he settled in England, pursued a career in the City of London and is regarded as one of the founders of the international capital market. On retirement, he moved to the Luberon region of Provence in Southern France, and he now lives in the Western Cape, South Africa. He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and a Freeman of the City of London. His previous works, Two Lives: A Social and Financial Memoir, Lives of the Luberon, James Grant and Short Stories were published by Austin Macauley. He is married to the former Diana Townsend and has three children.