Born in 1907, George Platt Lynes was a sickly boy who grew up during the era of Muscular Christianity, a social movement that promoted manliness and vigor. Fortunately, no one stifled the child’s poetic sensibility and love of beauty. George, while lacking in self-awareness, was destined for flamboyance, passion and artistry.

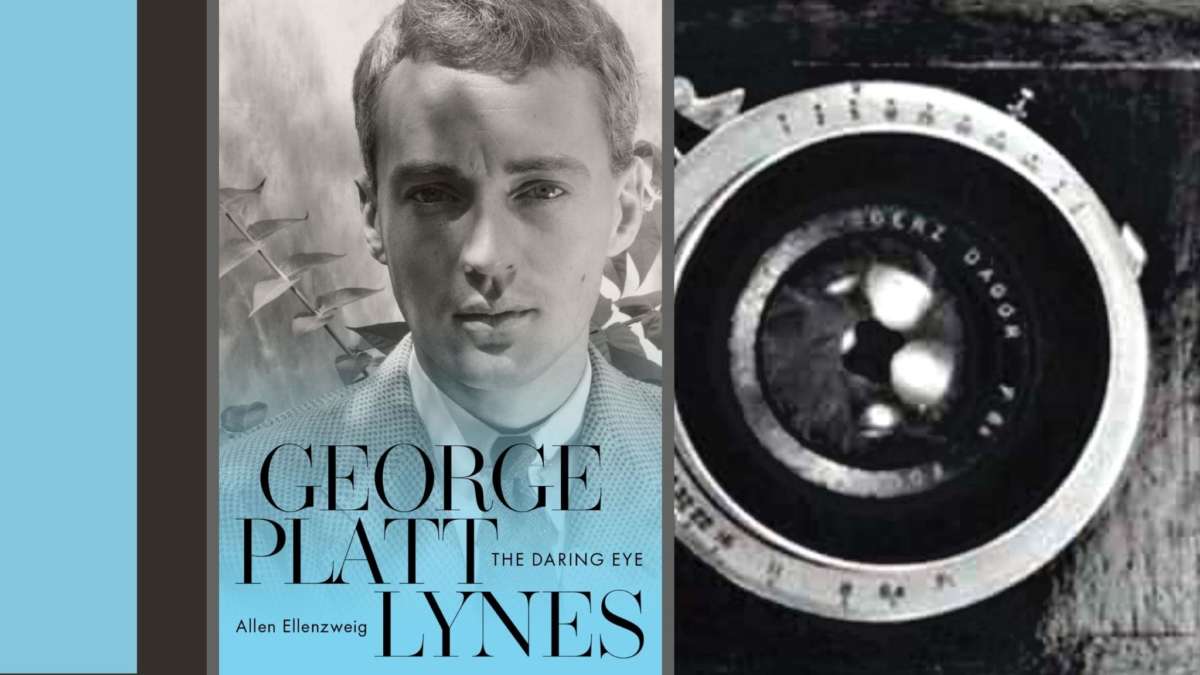

In George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye (Oxford), cultural critic and commentator Allen Ellenzweig has undertaken the first biography of the openly gay photographer, whose revolutionary use of shadow and light rendered him a particularly adept portraitist. George could “capture and reveal a certain quality in the subject that was always there but not always apparent,” one admirer would write of him.

Gertrude Stein counted among George’s first subjects, and he would go on to photograph such literary luminaries as E. M. Forster, Christopher Isherwood, Andre Gide, Thomas Mann, Katherine Anne Porter, W. Somerset Maugham and Ford Madox Ford. These writers were just a handful of the famous people George met in the swirl of transatlantic society during the 20th century — men and women he enticed into his studio, some of whom he seduced.

His later work would include fashion and dance photography and images of homoerotic encounters, which Dr. Alfred E. Kinsey used in his postwar studies of human sexual behavior.

Having left Yale abruptly after one year of study, annoyed with its stuffiness and exclusivity, George lacked “the standard academic credentials in his arsenal.” Voracious reading, attending the theater and ballet, museum visits, and growing familiarity with silent film enabled his transformation into a culturally literate mondain. Now he could find acceptance in social circles that ranged from “upper and lower Bohemia” to the beau monde. Doors opened while he dabbled in publishing and a bookshop venture, but his mood lurched from high to low when he realized he was not cut out to be a writer and fumbled in his quest for a vocation.

Everything began to change in 1926 when George entered the lives of Monroe Wheeler and Glenway Wescott. The couple, eight and six years older than George, cohabitated in Villefranche-sur-Mer, on the Mediterranean, and at 17 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. Occasionally they were colleagues as well as lovers, as Glenway’s novels gained notice and Monroe’s printing/publishing projects flourished.

George intruded on an imperfect relationship, argues Ellenzweig, debunking the conventional wisdom that he was a homewrecker. Both Glenway and Monroe were deeply attracted to George, and they swiftly became a triangle with “delicate emotional geometry,” writes the author. But it was Monroe who drew George’s greatest ardor.

“You run me off the chart of all language,” George wrote to Monroe soon after their first encounter. A few years later, George remained “choked with love” for Monroe, while the sex cooled between Monroe and Glenway. Eventually George, too, pushed Glenway out of his bed. Nevertheless, Monroe, George and Glenway would ultimately remain friends.

The three men made the most of the 1920s and ’30s, traveling between the United States and Europe during one of the historic periods of cross-pollination in Western art. At this time, Paris, Berlin and New York were especially influenced by the aesthetic of gay men, which was a heady experience for George, still a very young man and now, with encouragement from Glenway and Monroe, finding his way with a camera and a darkroom.

A “largely homosexual constellation of Harvard-trained professionals … would define modernist taste in America,” Ellenzweig observes. With the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan in 1929, George finally landed in the in-crowd. When the French poet Jean Cocteau came to New York, it was George who showed him around the city from Coney Island to the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem.

Even as George’s career took off — helped by his growing reputation as a fashion photographer — all was not well. He drank too much and depended on Benzedrine and phenobarbital. He also had established an unappealing modus operandi: “getting others to support him in a lifestyle he could barely afford.” While he apologized and made promises to his brother Russell and his sister-in-law, Mildred Akin, George increasingly exploited them for money.

“He was a manipulator more for his amusement than for what it might profit him,” Russell recalled years later. “Like many of his friends, I liked to please him.”

While George tried the patience of his brother and friends, Monroe’s trust in his lover declined. By 1942, when George began an affair with his studio assistant, sixteen years his junior, both George and Monroe recognized that their relationship had come to an end.

The young assistant did not hang around for long, though. Fortuitously, George received a job offer from Vogue, which sought a foothold in Hollywood. Becoming manager of the magazine’s new studio meant he could leave New York, now a dismal place full of memories, for California. He welcomed the opportunity to start over.

But of course, George was always starting over. “Infinite prospects, no money,” in the words of one friend. Ultimately, George wended his way back to the East Coast.

George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye bursts with detail about painters, sculptors, writers, photographers, performers, patrons and socialites during a thrilling time for art. From the end of World War I into the fifties, the emergence of modernism and expressionism profoundly influenced American and European culture. Allen Ellenzweig brings that world to life alongside George Platt Lyne’s artistic brilliance, complex temperament and untamed sensuality. The book is a breathless ride.

Brilliant, Claudia!