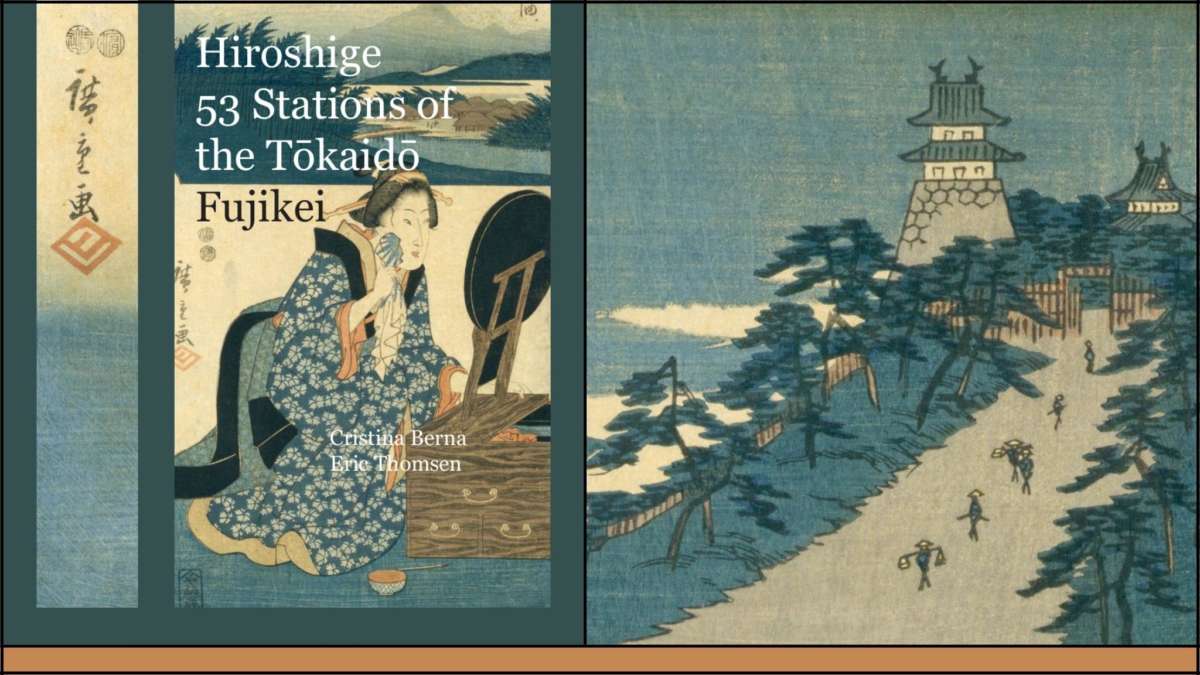

In browsing through the color reproductions in Hiroshige: The 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō Fujikei by Cristina Berna and Eric Thomsen, the reader is struck by the harmonious palette of blues, grays, peaches and pale yellows, and by the strict composition of each wood print — a bijin (or “beautiful person,” in this case, a woman) poses for the viewer in front of a framed landscape. Each print features the woman wearing a different, intricately patterned kimono, a different activity with various props, and a different landscape.

The 13th station: Hara-juku

While the series was never completed, this set of prints gave Hiroshige yet another opportunity to present a set of views from the Tōkaidō Road, a traveling route that traversed from Edo (now known as Tokyo) to Kyoto along Japan’s east coast during the Edo period (1603-1867). Over his career as an artist, Hiroshige had produced many editions of “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō,” each with a different set of scenes; the Hoeidō edition (1833-34) is among his most famous works and one of the best-selling sets of ukiyo-e prints ever made.

A NOTABLE ENTRY IN TŌKAIDŌ LITERATURE

Hiroshige was not at all the first to create a series based upon this subject matter. There had already been a long tradition of Tōkaidō art, including several series by Katsushika Hokusai (of “The Great Wave” fame), who preceded Hiroshige; contemporaries including Utagawa Kunisada; and Fujikawa Tamenobu and Kano Shugen Sadanobu after him, among many others.

Traditionally, a Tōkaidō series covers in sequence the 53 “stations” or shukuba along the route, with additional scenes of the start and end points for good measure. Shukuba were rest stops for travelers that included lodgings for various ranks and classes of individuals, retail stores, tea houses and the like. They were also used as government checkpoints for traveling permits. Most of the stations were built in the early 1600s, and some still exist today, including villages that have either remained intact or undergone reconstruction thanks to preservation efforts as cultural heritage sites.

Each print in a Tōkaidō series covers the sights, people or activities a traveler may encounter along the route, as roughly demarcated by each shukuba. The images can vary from landscapes to close-ups of nature, busy village scenes, and mythological or theatrical references.

In Hiroshige’s Fujikei edition, we see the Tōkaidō stations at a distance “once removed” — as art on a wall. It’s a concept that invites postmodern interpretation, but it also is a bit daring for the era. During the late Edo period, images of “morally questionable” subjects such as actors, courtesans and other entertainers were outlawed. Inserting these subjects into more acceptable formats such as landscapes was a way to circumvent these edicts. By way of dress, many of the women in the Fujikei series are identified as courtesans of one type or another; by pushing the landscape back to a picture hung on a wall, Hiroshige makes the boldest move possible in depicting otherwise “forbidden” subject matter. It is a technique he would revisit again in his collaboration with fellow woodblock print designer Kunisada, a work known as the “Two Brushes Tōkaidō” series.

“The pretty ladies here are integral to the Tōkaidō,” write Berna and Thomsen, “They are performing functions that are the Tōkaidō. They are part of a dream, a state of fluid other-world, where the dream is real and the real world is a dream, but at a price, of course.” This “floating world” (a literal translation of the term ukiyo-e) is both stylistic (in terms of intricate detail and lack thereof) and idealistic (the “perfect beauty” of the women is such that it could well be the same woman in each print, her features are so similar). The woman and the picture on the wall literally float on a background that could be indoors, might be outdoors, just a wash of blue gradient for foreground.

PART OF A LARGER ART HISTORY EFFORT

The 32nd station: Shirasuka-juku

In their book, authors Berna and Thomsen take us on a fascinating tour of the Fujikei edition, explaining not only the cultural references in the prints, but also the relation of the Fujikei prints to several earlier Hiroshige Tōkaidō series. Along the way, we get a full lesson on the history and culture of late Edo-era Japan and in-depth biographies of Hiroshige and Fujiokaya Keijirō (Shōrindō), the printer of the Fujikei edition.

But their curation doesn’t end there. Berna and Thomsen have published dozens of volumes on various Tōkaidō series from multiple ukiyo-e artists, as well as other series by Hokusai and Hiroshige — all featuring their expert and fascinating commentary. Hiroshige: The 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō Fujikei is just one piece of a much larger project that’s as ambitious as it is awe-inspiring, coming as it does from a pair of non-academics.

In the West, the most enduring legacy of Hiroshige’s work is his influence on European artists such as Van Gogh and the Impressionists Manet and Monet, and more generally as part of the wave of Japonisme in European art in the late 19th century. In the East, though, Hiroshige is considered to be the last great master of the ukiyo-e tradition. Not long after Hiroshige’s death in 1858, Japan’s center of power shifted back to the imperial emperor, the feudal governance of the shogunate was all but dismantled, and Japan’s ports were reopened to the Western world, bringing about industrialization, modernization and concomitant cultural change. Soon railways would supplant walking as a means of transport, and travel via routes such as the Tōkaidō waned in popularity.

After gazing upon the beauty of such prints, it is sad to realize that the work contained in Hiroshige: The 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō Fujikei stands among the last windows into the world of pre-modern Japan. It is a book full of sights — and insights — to treasure.

—∞—

Hiroshige: The 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō Fujikei is available as a large-format paperback, and more compact hardcover and paperback editions.https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cristina-berna300.jpg

About the Authors:

Cristina Berna loves photographing and writing. She also creates designs and advice on fashion and styling.

Eric Thomsen has published in science, economics and law, created exhibitions and arranged concerts.