I have three priorities this October: launch my pregnancy memoir, submit my next novel before its deadline (okay, at least by its deadline), and pour over, lavish inside, and dwell on Elizabeth Strout’s latest book, Oh William!. Everyone admires Strout for her telling details, shrewd insights and languorous mood building, but I owe her a particular debt: her work gave me reason to persist with the characters who fascinated me.

When I began as a novelist, the response from publishing professionals was that my lineup of ragtag gal protagonists were too “unlikeable.” That was the universal descriptor, though some editors zeroed in on the specific traits that put them off: bitingness that bordered on cruel, vanity, and the most condemnable crime, infidelity. “Maybe we could try to forgive her if we hated her boyfriend?” one suggested. That was when I began to suspect a heroine’s mistakes couldn’t be mistakes at all, but technical infractions justified by context.

While we could be interested in, and even rally behind, any kind of man — the mob boss, the drug dealer, the asshole, the lothario, and the lowlife who was all those things — we held women to a higher standard. Readers couldn’t get past my characters’ faults to see who else they were. They could be nuns who valiantly took on the Catholic Church or war pilots who defied convention as well as gravity. That was all well and good, but if I wanted my books accepted for publication, it appeared those ladies must also be on their best behavior.

I was about to lose hope, ready to scrub manuscripts, soften characters, emphasize acts of charity, and redeem any shortcoming left behind with old-fashioned “save the cat” moments (or, as a canine lover, save the dog).

Then, I stumbled on Olive Kitteridge, a female character with thorns to spare, including having been unfaithful to a very kind man. She’s judgmental, cruel, self-destructive, withholding, and stormy, or, as Strout put it in the first chapter, “she had a darkness that seemed to stand beside her like an acquaintance that would not go away.” She steals her daughter-in-law’s loafer and fantasizes about the self-doubt the theft will incite. She belches and has explosive diarrhea. She says the wrong thing and keeps the right things inside. Okay, there is the “saves the girl from drowning” moment, but otherwise, the woman is insufferable.

And yet readers care for her deeply, because Henry neglected her; because her father was suicidal; because she’s so starved for love that, when she visits the dentist, his tender touch brings tears to her eyes; because she hurts and she’s human. Because we’re human.

Nobody is defined by their flaws, not even women. My nun wasn’t just gruff. She was bighearted. She was fiercely loyal to some while being unfair to others. She was complicated, contradictory, joyous and damaged. She was real. To be so turned-off by the mistakes of women, or to refuse to forgive them, is to dehumanize them. Flaws define us, along with our many other qualities and experiences, and to whitewash female characters is to tell the partial story of the human experience — the woman’s experience — and to perpetuate a romanticized view of our gender that we can’t live up to, and shouldn’t even try.

There can’t be one type of female character (gracious, nurturing, humble, kind, and just the right amount of brave) because there isn’t only one type of female. If art doesn’t imitate life, we might look at life and think we’re doing it wrong. If we turn to stories and perpetually find the same sort of woman, who is, in many ways, unrecognizable, then we might begin to suspect we are the aberrations with the wrong bodies, pregnancies, romances and feelings about motherhood, when, really, there is no right, there is only ours.

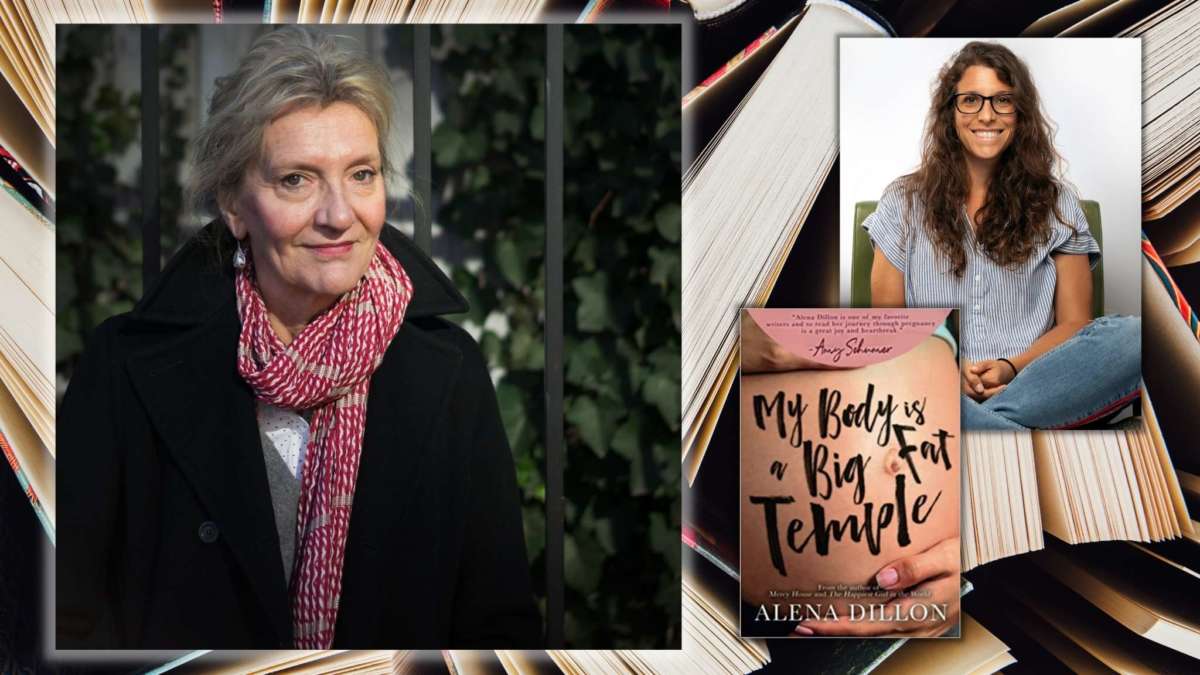

Olive bolstered my conviction that the world could care about many types of women, and should, so when my then-agent insisted I reimagine my character’s abrasive nature, I responded the way Olive would have, saying, “Not keen on it.” The agent dumped me, but a decade later, I have two published books featuring unvarnished warty broads, and two forthcoming, including a memoir of pregnancy and motherhood, which is, perhaps, the epitome of manifold femaleness, as well as a reinvention of my war pilot novel.

All Strout’s novels are similarly populated with rich female characters with deep inner lives, including My Name Is Lucy Barton, whose protagonist we will revisit in Oh William! just as we were reacquainted with Olive in her sequel, Olive, Again. If you’re wondering what I’ll be doing on October 19, it is savoring her next installment word by intentional word, delighting in the artistry that inspired me to keep creating, and believing.