If you have a health problem that you feel a little ashamed to admit to your friends, and when pressed you just vaguely call “stomach issues” before changing the subject, you’re not alone. Also, you should not be even a little bit ashamed. As it turns out, a huge number of people struggle with the same symptoms or have the same problem with different manifestations, and you all deserve some real answers with an encouraging professional giving them to you.

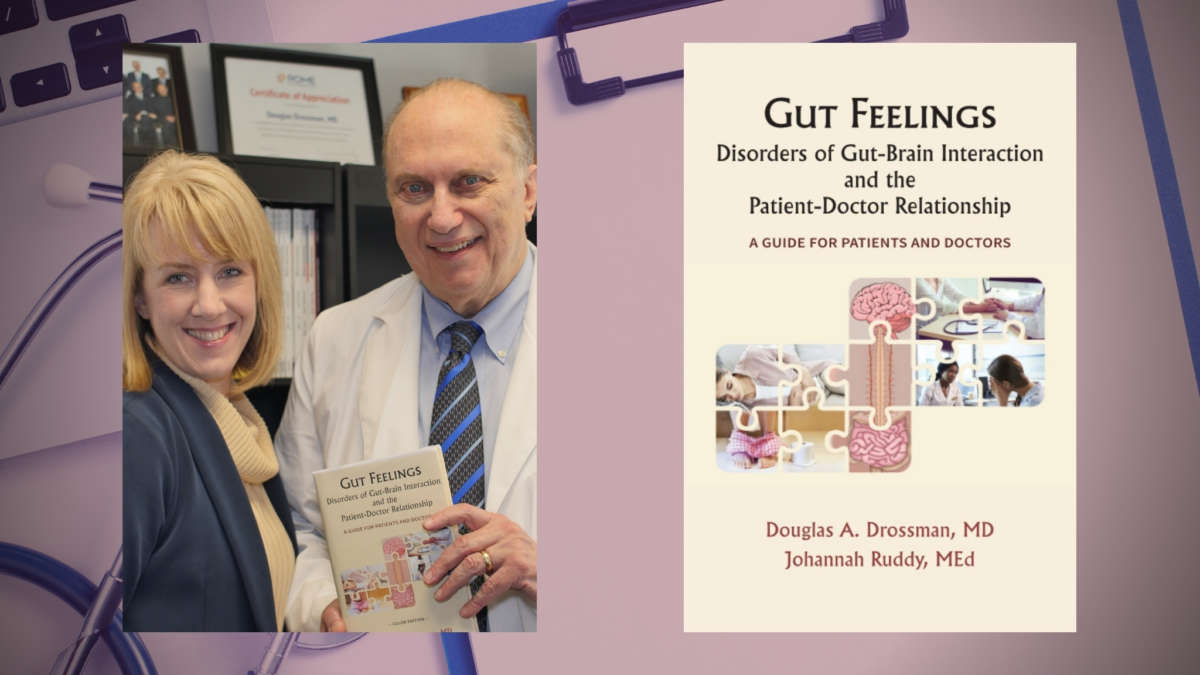

Meet Dr. Douglas A. Drossman and Mrs. Johannah Ruddy, coauthors of the new book Gut Feelings: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction and the Patient-Doctor Relationship and the team leading the charge of the Rome Foundation, a soft place to land for anyone, and everyone, who suffers from the often-dismissed difficulties. We asked the pair some hard-hitting questions that get down to business and start dismantling the myths, and got some clarifying answers that further prompt us to read their book all over again!

We cordially invite you to read our review of Gut Feelings: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction and the Patient-Doctor Relationship and check out the author profile page for the intelligent and enlightening Dr. Drossman and Mrs. Ruddy.

Q: What exactly are Disorders of the Gut-Brain Interaction?

A: The disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) are common gastrointestinal symptoms, previously referred to as functional gastrointestinal disorders (Q & A The Brain-Gut Axis – Rome Foundation). These disorders are defined by a collection of symptoms in the absence of structural findings, as seen on x-ray or endoscopy and normal laboratory studies. The characteristic symptom patterns establish the diagnosis, which is made using the Rome Criteria. For example, irritable bowel syndrome is defined by Rome criteria as abdominal pain associated with a change in bowel habit (i.e. more frequent, loose stool — IBS-D; or harder and less frequent stool — IBS-C) absence of structural or laboratory findings.

The determinants of DGBI are based on any combination of the following:

Motility disturbance — An abnormality in how the gastrointestinal tract moves. If too slow, you have constipation; if too fast, diarrhea

Visceral hypersensitivity — A “sensitive gut”; factors affecting the bowel, like eating or the movement of the bowels, lead to more discomfort or pain in some than in others because the nerves are sending stronger signals to the brain

Altered mucosal and immune function — This leads to visceral hypersensitivity. The nerves are more sensitive because of increased chemicals called cytokines or “leaky gut,” i.e., a loss of barrier function of the lining of the bowel, or dysbiosis (bad bacteria)

Altered gut microbiota — There is an imbalance in the good and bad bacteria. The bad bacteria produce altered mucosal and immune function. Sometimes this is related to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

Altered central nervous system processing — This relates to when the normal coordination of functioning of the nerves between the brain and gut (brain-gut axis) are impaired.

Q: What should a patient do if they feel that their doctor isn’t taking their symptoms/illness seriously?

A: This is discussed in detail in Part 3 of the book, pages 118-121. In brief, patient-centered care requires that there be a collaborative relationship between doctor and patient. As discussed in the book, the DGBI are not identified by structural abnormalities seen on x-ray or endoscopy, and that may be misinterpreted (by patient or doctor) as “there isn’t anything wrong”. But with the definitions we have of DGBI, we know scientifically of its reality.

This may be why sometimes doctors who are not fully educated in DGBI may consider these patients as “second class” and may treat the patients without the same interest and attention as a structural diagnosis like ulcer disease or IBD where there are abnormalities on testing. In part, this reflects the doctor’s lack of knowledge or a full appreciation of these disorders. If the doctor doesn’t understand or feels unable to manage these disorders, they may inappropriately ignore or even stigmatize the patient (Stigma – Rome Foundation).

When the patient feels their symptoms are not being taken seriously, they may question the doctor by reflecting on their experience rather than criticizing. This may seem hard to do at first, but it brings the issue clearly to the doctor. “Doctor, I’m not sure I’m being clear on how bad these symptoms are and how it’s affecting my life. Is there anything more I can tell you about what I’m experiencing?” This allows the doctor to respond in kind with a greater sense of understanding.

If the doctor continues not to take the symptoms seriously, the patient needs to readdress more assertively. “Doctor, I feel like I’m not being heard. I’d like you to understand what I’m going through and try to help”. If at this point the doctor is still not taking the symptoms seriously, the patient may need to look at other options for care.

Q: What got you interested in this disorder in particular, Dr. Drossman?

A: DGBI represents a blending of mind and body, and this is an area that fits well with my interests and skills. I’m trained in gastroenterology and psychiatry. I chose gastroenterology because it met my need to combine medicine’s technical aspects with a strong focus on the patient. It is a blending of science and art. My psychiatry/psychosomatic medicine training was with my mentor George Engel who coined the term “Biopsychosocial Model”. He taught me that concept which has been the driving factor in my research, teaching, and patient care for over four decades. He also was a master in the medical interview. With that combined training, I evolved the concept of brain-gut interactions and patient-centered care. So, in the early 1990’s I founded the Rome Foundation and have been president until 2 years ago and now serve as chief operating officer. I also set up DrossmanCare to develop educational programs to enhance the patient-doctor relationship, and it’s been a perfect fit.

This was all enabled and amplified by my patient care since my practice brings in the most challenging clinical cases, usually of patients struggling with pain and other GI symptoms. They are frustrated by the healthcare system where the DGBI are minimized and stigmatized. I started seeing patients who “failed” elsewhere and identified factors to help explain why patients were doing so poorly with my interviewing skills. This led to me doing research studies to confirm that. I sought to bring science into understanding the reality of the patient’s experience. I was well funded with NIH grants and established a lot of the knowledge to help the patients with these disorders. I was the first to identify the role of early trauma in medical and GI symptoms and to characterize the quality of life and health outcomes of patients with DGBI. We developed many of the research instruments on health status assessment and quality of life to accomplish all of this. We even did brain imaging studies to show how trauma makes the pain control area of the brain not work so well. Then we were the first to do a large NIH clinical study to confirm the value of antidepressants (neuromodulators) and cognitive-behavioral treatment in these disorders.

Fortunately, this work has grown through the many other investigators, teachers and clinicians who followed in the last few decades. Many of the leaders in the field are people I trained or collaborated with. However, while patients with these disorders comprise about 40% of GI practice and are the most common GI disorders in primary care, the disorders are underrecognized and at times even delegitimized by the healthcare system and patients. So my mission is to reverse this.

Q: How did it feel to finally end up with a doctor who was committed to helping you, Johannah?

A: After more than 10 years of struggling with severe abdominal pain, unpredictable bowel habits and eating a very limited and restrictive diet, I had given up on doctors ever being able to help treat my symptoms. My history of seeing physicians diagnose and treat my condition had only left me frustrated, hopeless and in debt. I was resigned to manage the best I knew and adapt my life around my symptoms. The thought of seeing a new doctor, explaining my symptoms and history, and waiting on additional testing to try to determine a diagnosis was exhausting even to consider. I was done and resolved that this was my life now.

When my family moved to NC about 4 years ago I saw Dr. Drossman at the urging of my husband, as we started working together and because of his recognition in the field. However, I did not think that my experience with him would be any different than any other physician I had seen in the past; why would it? Much to my surprise, my first clinic visit was an entirely new experience. My previous visits with physicians were always rushed and hurried. I never felt like I had the doctor’s full attention or that they were really listening or cared. That was not my experience with Dr. Drossman. We spent time reviewing my health history and its impact on my quality of life, my family, and my emotional well-being. I felt that he understood and cared. Instead of leaving me hopeless without any answers, he provided a diagnosis and the commitment to work with me as a partner. This was life-changing for me. It was validating and therapeutic to be believed, shown empathy and treated as a partner in my own medical care. Through a few years of working together to find management for my symptoms, I have regained my quality of life, gained more resilience and the ability to better communicate and advocate for myself and keep my chronic symptoms under control. Here is a video of my story. This experience also led to a collaborative partnership in educating others on DGBI. We now publish articles together, do workshops for clinicians and of course published Gut Feelings together.

Q: What is the Rome Foundation and what does it do? What is its mission?

A: The Rome Foundation is an international non-profit academic organization whose mission is: “To improve the lives of people with disorders of gut-brain interaction”. There are four goals:

- “Promote global recognition and legitimization of DGBI

- Advance the scientific understanding of their pathophysiology

- Optimize clinical management for these patients

- Develop and provide educational resources to accomplish these goals”

Dr. Drossman founded the organization in the early 1990s, served as president until 2019 and now is the Chief of Operations with President Jan Tack MD in Belgium. Our activities include developing the diagnostic criteria for DGBI (Rome IV criteria) used in research and clinical practice and doing a large variety of educational programs around the world. Johannah Ruddy is the Executive Director of the Rome Foundation. There are so many activities.

Q: What is the biopsychosocial model of care and how does it differ from our current doctor-centered care model?

A: The biopsychosocial model was first mentioned by George Engel MD, an internist and psychoanalyst who was Doug Drossman’s mentor when he was in training in psychiatry and psychosomatic medicine at the University of Rochester. In his seminal publication in the journal Science in 1977 he stated: “The dominant biomedical model of disease leaves no room within its framework for the social, psychological and behavioral dimensions of illness”. He then went on to say: “A biopsychosocial model is proposed that provides a blueprint for research, a framework for teaching and a design for action in the real world of healthcare”.

These words overcome the deficits of mind-body dualism in medicine. Biopsychosocial means that the brain and the body interact and influence each other. Bio, is short for biological; psycho refers to the psychological or mental component that affects our bodies; and social refers to the social aspects of our lives, including family, friends, and other environmental factors that play a role in DGBIs. Here is a video that explains mind-body dualism and the biopsychosocial model.

Because we have learned that the brain and gut interact physiologically through the “brain-gut axis,” the biopsychosocial model is the conceptual basis for this reciprocal interaction that helps us to understand and treat DGBIs. The biopsychosocial approach acknowledges and incorporates a role for the patient’s experience in illness and disease, and vice versa.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Douglas-Drossman-round-300×300.jpg

About Douglas A. Drossman:

Dr. Drossman is trained in gastroenterology and psychiatry and was the founder and co-director of the Center for Functional GI and Motility Disorders at the University of North Carolina. He is an internationally recognized scientist, clinician, and educator in DGBIs and communication skills training. He has written over 500 peer-reviewed scientific articles, published 15 books, and was awarded numerous federal research grants. He is the founder, former president, and current COO of the Rome Foundation. As president of DrossmanCare, he produces educational videos and develops workshops and training programs in communication skills. His internationally recognized gastroenterology practice receives patients with difficult-to-diagnose and manage DGBIs.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Johannah-Ruddy-round-300×300.jpg

About Johannah Ruddy:

Mrs. Ruddy is a patient and patient advocate with a background in education and a career in non-profit management. As Executive Director of the Rome Foundation, she coordinates operations and educational programs. With DrossmanCare, Ms. Ruddy facilitates workshops in patient-centered care and is a simulated patient in videos on communication skills. Ms. Ruddy can articulate her experiences in a way that educates doctors and motivates patients to self-actuate and assume responsibility in their care. In this regard, her social media presence is well recognized, and she has published four peer-reviewed articles in scientific journals on patient advocacy and the importance of the patient perspective in medical education.