“Consumed by a far-flung odyssey, coming up only for a sip of water … I inhaled Fifty Words for Rain in one day.”

—The New York Times Book Review

—∞—

“A lovely, heartrending story about love and loss, prejudice and pain, and the sometimes dangerous, always durable ties that link a family together.”

—Kristin Hannah, New York Times bestselling author

—∞—

“A gripping historical tale that will transport readers through myriad emotions … bringing us to anger, tears and small pockets of joy. A truly ambitious and remarkable debut.”

—Booklist

—∞—

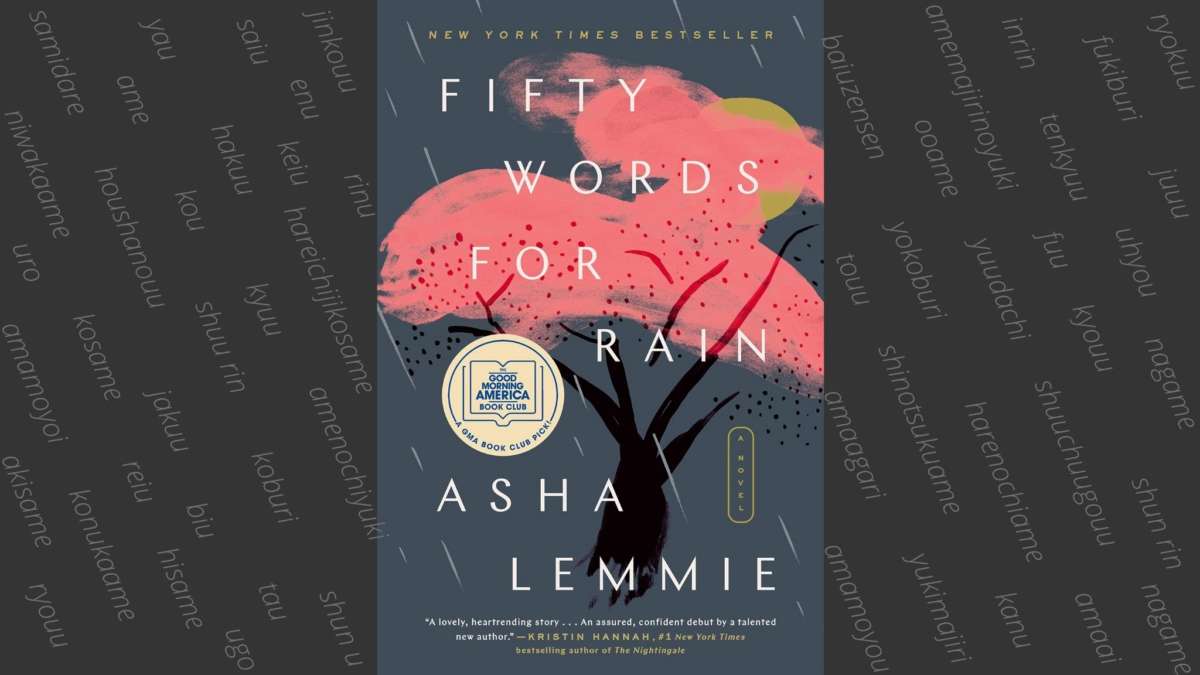

I was swept up in the debut novel by Asha Lemmie and I am not the only one! A Good Morning America Book Club Pick, an Amazon Spotlight Pick and Best Book 2020, a Barnes & Noble Discover Book, and a New York Times bestseller, Fifty Words For Rain (Dutton), is an epic coming-of-age story that spans years and countries.

It begins with Noriko, the abandoned daughter of a woman from a prominent Japanese family and an African American soldier. Mixed-race with dark skin, her existence is so shameful to her family that she is hidden away in the attic of her grandmother’s estate in post-WWII Japan. Suffering unthinkable abuse and neglect, Noriko (Nori) questions who she is and what she deserves, longing to be out in the world and loved by family. When her half brother arrives at the grandparents’ estate, he chooses to show Nori kindness and fight for her freedom, allowing their special bond to give her strength and hope.

This the story of a resilient young girl and her search for identity. The novel gives us background on post-World War ll Japan, includes a touch of classical music, and provokes wonderful discussions on tradition, the power of family and how loyalty impacts the choices we make. I really enjoyed this book and my book club had an open and insightful discussion with the talented author.

Author Q & A

Q: I would love to know more about your personal story. Can you share a bit about your family (siblings/parents), where you grew up, went to school, what you were like as a kid, when you started writing?

A: I started writing young. I was a weird, unhappy, socially isolated child with few friends. Most of my friends were the children of my stepmother’s friends — my “aunties” — first-generation American kids who divided their time between countries, many of whom were multi-racial, multi-cultural, adopted, etc. I only felt at home around them and their worlds — not around what I was “supposed to” — and I’ve been pondering the question of identity ever since.

Q: How long did writing this book take you?

A: It took 10 years chronologically from the first day a word hit the page for the book to be published. But if I count up all the time I was actually writing, and not just thinking about writing, I would say it was about three years. Publication is a slow process. I signed the deal a year and a half before the book hit shelves. People tease me that I look the same, but I’ve changed a lot on the inside throughout this journey.

Q: Because you started writing this novel at such a young age, I am wondering what sparked the idea for this story of a mixed-race girl being kept in an attic by a relative?

A: I wish I could point to one singular instance. I think it’s just my love of history, combined with my feelings of isolation and divergent identity, combined with my close relationships with my Japanese aunties, combined with that spark of imagination that all fiction writers must possess.

Q: Your main character, Nori, faced abuse for many years. Where do you think she got the strength to keep on going?

A: I think we don’t know how much strength we have until we are tested. At some point you have to make a choice: you lay down and die, or you live. It’s that simple and that complicated. Sometimes all you need is the faintest hope, and for Nori that comes in the form of her brother.

Q: Half siblings, Akira and Nori, have an unusual relationship. Without even knowing each other, Nori is desperate for his love and Akira risks his future to stand up for her. This younger generation has a different approach to family and loyalty than their parents and grandparents. Why?

A: The old guard is, generally speaking, always more traditional than the new. The sense of duty that is so prevalent among older generations does not always get passed down. Even though Akira is in a privileged position with the family, he still feels stifled and trapped, unable to fully pursue his own ambitions as an individual. So I think he has no love for the stuffy confines that hold him, and is able to sympathize with the confines that hold Nori. I also think he’s very curious about her and the link that she holds to their mother.

Q: I was so invested in the relationship between Nori and Akira that after the accident, I couldn’t imagine how you would keep my interest, yet I continued to be drawn in. Did you map out Nori’s life journey ahead of time to ensure her compelling storyline, or did it just evolve?

A: I think it just evolved. I really struggled with what to do after Akira’s departure (even though I knew from the beginning that it had to happen) and re-wrote that bridge from the late middle to the ending several times.

Q: Can you share something you initially included in the book but ended up taking out?

A: So much! I toyed with the idea several times of having Nori and Akira’s mother reappear, but it just didn’t feel right. Not yet.

Q: Nori does a lot of tree climbing … did you ever climb trees as a kid?

A: I am wholly uncoordinated, but I always wished I could.

Q: In the end, why did you decide to have Nori leave a life of love and stay in Japan?

A: There are a couple of answers to this question. I think one is that, for better or worse, everything is a cycle, and I think that Nori going from the cursed bastard in the attic to head of the family is as full circle as it gets. I disagree strongly with the notion that her stepping into her grandmother’s shoes means that she is destined to become her grandmother. I think if she’s aspiring to be anyone, it’s Akira.

I think another answer is that it’s very difficult for Nori to accept love, but it’s much easier for a historically powerless person to jump at the opportunity to have power — agency over her life and the lives of others. One must also consider that Americans are conditioned from a young age to be very individualistic. I think this pandemic has pulled back the curtain on how “me” centered American culture is. It’s not like that in other places in the world. There’s a sense of collectivism, and sacrificing one’s personal happiness for the good of the whole. I think after the life Nori has had, she feels that purpose > happiness.

Q: Nori’s grandmother is such a villain. How did you develop her character, and is she modeled after anyone you know? (She reminded me of Cruella de Vil!)

A: If she were modeled after someone I know, I would keep that to myself for fear of retaliation, haha! I think Yuko is a product of her time and the pressure that she feels to keep the ship afloat, so to speak, even though she is a woman. She has to be tougher, she has to be more ruthless in order to command respect. I also think she doesn’t see herself as a villain. The best villains never do.

Q: How did you develop your characters? Do you come up with who they are before the story or do they write themselves?

A: They write themselves most of the time. I may start with a seed, but the way they bloom is always exciting to watch.

Q: Do you think the connection to family can be too strong — even to its detriment?

A: Yes. Blood is thicker than water, they say, but sometimes the people we’re bound to by DNA are the most toxic of all. I am a big believer in found families — I have a lot of them.

Q: What is your connection to Japan? How did you learn about/research prominent Japanese families in the 40s?

A: Well, I do have a personal connection (back to that idea of found family) but even if I didn’t, it’s fiction. Historical fiction in particular has never been a genre where people are limited to writing about their own exact experiences. If it were, it wouldn’t exist, since most of us were not alive a hundred years ago, haha!

I’ve spent a lot of time reading books and watching documentaries about aristocracy, WWI and WWII. The Kamiza family is fictional, but it’s based on the historical reality of the Japanese House of Lords being dismantled after WWII and the monarchy becoming a figurehead. Power is always difficult to give up, and I wanted to explore how one family might have struggled with that.

Q: Music is a beautiful way people connect, and Nori and her brother were lucky to have had this in common. Do you play an instrument, did you perform, and did the musical pieces you mentioned in the book (“Ave Maria,” etc.) have any special significance to you?

A: I do play instruments and I did study opera. I love classical music and often write to it. “Ave Maria” is my favorite piece from childhood.

Q: I love how you used written letters to give us important background information on Nori’s mother. How did you decide to use that tactic?

A: I think I realized that even if Nori’s mother wasn’t physically present, she was still an important character. Our written words are a portal to us, even when we are gone.

Q: Do you think Nori will ever feel she deserves love, or do you think she is damaged beyond repair?

A: I think this idea that trauma just vanishes is silly. It heals in a manner of speaking, but it has a way of seeping into the bone marrow. It does change us, but that doesn’t mean we can’t conquer it, and not let it rule us. I also think the idea that character development has to be wholly linear is silly. We can fall, we can take two steps backward, we can take a disastrous wrong turn — but there’s always hope.

Q: Would you consider writing a sequel?

A: Hah! I get asked this question a lot. I can honestly say that when I wrapped up this novel I had no plans for a sequel, but now I’m considering it.

Q: How and when did you come up with the title?

A: There’s a saying that there are fifty words to describe rain in Japanese since it rains so often in Japan. It’s a great metaphor for the ups and downs in life, so I ran with it.

Q: What have you read lately that you recommend?

A: White Ivy by Susie Yang.

Q: Are you working on another book and if so, can you tell us what it is about?

A: I am. It’s another coming-of-age story/historical fiction centering on a young girl trying to find her family and place in the world. It’s very different but has similar notes. This one takes place in Paris/New York/Cuba.

—∞—

Fifty Words For Rain is available for purchase. Enjoy Lemmie’s Spotify Playlist to accompany your reading of the book!

Searching for one’s identity comes up in books quite often. Here are more great books I recommend with that similar theme.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/asha-lemmie-crop300.jpg

About Asha Lemmie: