https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/booktrib_JackHersch_authorspotlight.jpg

Advances in aviation technology have given pilots the ability to switch into “autopilot” and essentially let technology fly the plane. This opens the possibility that pilots will lose focus and not be prepared if they need to manage a crisis, which can easily happen.

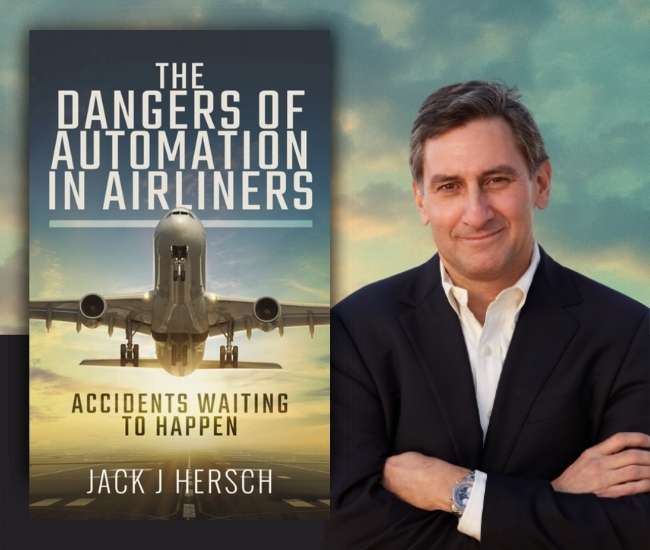

In The Dangers of Automation in Airliners: Accidents Waiting to Happen (Air World), author and instrument-rated commercial pilot Jack Hersch puts readers right in the cockpit of nine flight incidents so they can gain a complete and intricate understanding of the benefits and hazards of automation.

“With the possibility of 100 or more deaths at one time in a single airliner crash, each one is crucially important to understand what happened and why,” says Hersch. “There are life-saving lessons to be gleaned by studying them. I wrote the book to save those lives.”

Hersch offered more insights and perspective into the topic in a recent Q&A:

Q: Describe the importance you put on the state of the pilot and how automation compromises that state.

A: Automation has changed the role of airline pilots, from being pure hands-on flyers using physical skills they’ve spent years mastering, to being flight managers spending most of their time as observers. When their plane is under control of automation, which on long flights may be 95 percent of the time, it is critically important that pilots remain highly alert and vigilant, aware of every constantly changing data point about their plane and flight.

But that is extremely hard: Minds wander, vigilance lapses and fatigue can set in, especially because pilots know automation failures are so rare. So they can get away with sometimes losing track, or not being hyper-focused on their flight 100 percent of the time. But experience has shown that if something goes wrong when the pilots have lost track, disaster can strike. And even if their vigilance is perfect, instantly switching in an emergency from monitoring to troubleshooting and hands-on flying is very difficult to do and has cost lives.

Q: Of all the incidents you write about, what is the biggest example of failure in automation?

A: I don’t believe the book has a single biggest example because each of the flights I describe was so unique. But automation was equally the direct cause in three incidents I describe: two crashes of Boeing’s new 737 MAX, and one non-crash, Qantas 72 near Australia. In each of those cases automation physically took over the plane and fought with its pilots for command. You can’t have a greater failure than automation grabbing the controls.

On the other hand, I describe four other crashes where automation failures caused the pilots to make grave mistakes, which led to crashes. In those cases, the automation failures exposed weaknesses in piloting skills that have come about because pilots’ hands are not on the controls as often as they once were.

Q: Your first book, Death March Escape, was such a personal book. How different was it to write this one?

A: I would characterize this book as highly personal, as well, though in a different way. The first book, Death March Escape, was about my father’s experiences in, and escapes from, a Nazi concentration camp, and then my story of visiting that camp. I listened to him tell his stories of survival and escape so many times during my life that while writing the book, his voice was literally in my head.

But I have a visceral love for aviation and have since my childhood. At seven years old I could tell you what every cockpit instrument did. Writing about something that I am so connected to was highly personal as well, though in its own way.

Q: What was the most difficult part of this book to write?

A: There was a large research component necessary even before I put my first words on paper, but it was time-consuming more than it was difficult. What was truly difficult was studying the official government accident reports on each crash — or non-crash — and their second-by-second information on the flight and translating that into a coherent narrative of what the pilots were doing, and what the plane and its automation were doing, in a way that a layman could easily follow and understand.

Q: Did you ever know any pilot personally who was killed in an air crash?

A: I have many flight hours of training as an aerobatics pilot, and two of the five aerobatics instructors I’ve had over the years died in aerobatics plane crashes. But as for commercial flying, I don’t know anyone who had lost his or her life in a plane crash.

Q: When flying, how close did you ever come to having to deal with a malfunction in airline technology, and how did you handle it?

A: In almost 40 years of flying small planes, I’ve never had a serious incident of any sort related to automation. But that is perhaps mostly because I use very little automation in the small planes I fly — I like to have my hands on the controls. But along the lines of emergencies, early in my flight training, I was alone on a practice night flight when a bird struck my windshield, scaring the daylights out of me and forcing me to react calmly. After hearing a tremendous BANG that shook the plane, my cockpit instruments told me nothing had changed. I realized we had hit a bird because I shined a flashlight around the cockpit and the windscreen was filled with blood and feathers. I was in radio communication with the airport tower, so I radioed that I had had a bird strike and wanted to return. The air traffic controller immediately vectored me back toward the closest runway and kept checking on me as I gingerly flew the plane back in and landed it.

Q: Do you think people will be scared to fly after reading your book?

A: I think “scared” is too strong a word, but I do think readers will probably be more aware of the dangers inherent in being shut in a tube seven miles up in the stratosphere moving at nearly the speed of sound. But they have to weigh that extra awareness against the true risk they’re taking. The chance of dying in an airliner crash is around the same as that of being struck by lightning. Reading the book won’t change those odds. But if my book moves the airline community a step closer to better training and safety, then readers should take comfort knowing that things are improving.

Q: What’s your next project?

A: I enjoy learning about WWII as well as about technology, aviation and finance. They are all exciting areas with many stories that haven’t yet been told, and I have a few potential projects in all of them.

Read our review of The Dangers of Automation in Airliners here, and check out Hersch’s BookTrib author profile page here.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/amazon-button.jpghttps://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/indiebound-button.jpghttps://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/bookshop.jpghttps://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/JackJHersch.jpg

About Jack J. Hersch:

Jack Hersch is a journalist, an instrument-rated commercial pilot and an expert in the field of distressed and bankrupt companies. He has served as a public company board member and has guest-lectured at prominent business schools. This is Hersch’s second book. His first, Death March Escape, was the winner of the 2019 Spirit of Anne Frank Human Writes Award. He and his wife live in New York City.