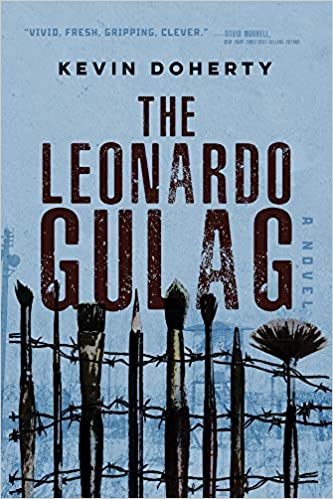

The Leonardo Gulag

January 1950. Three a.m. in a small town outside Moscow. Asleep on a sofa in a grim apartment that he shares with his mother, 20-year-old Pasha Kalmenov is awakened and arrested by militiamen. Along with 19 other artists, he is put on a train headed north to the bleakest reaches of the USSR, to one of the forced labor camps of the gulag. Here, in the freezing cold, under close guard, under a portrait of Joseph Stalin and a sign “He who does not work, neither shall he eat,” these 12 men and eight women will work … to forge drawings of Leonardo da Vinci.

So begins The Leonardo Gulag (Oceanview Publishing) by Kevin Doherty.

This is thrilling new fiction. To put it into perspective, Doherty provides some sober historical fact:

During January 1950, in England’s Windsor Castle, elegant and patrician Sir Anthony Frederick Blunt, age 42, a third cousin of the wife of King George VI, held the position of Surveyor of the Royal Collection. It contained (and still does) hundreds of da Vinci’s priceless drawings, over which Blunt had complete control.

And Blunt’s avocation in the 1950s? In the last decade, he had “shared with his friends in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics enough operational documents and classified papers detailing the secrets of his country’s government and intelligence services to fill a small removals van.”

(On April 23, 1964, in return for full immunity from prosecution, Blunt confessed his treachery to MI5. Did his crimes include walking off with hundreds of da Vinci’s drawings and giving them to his Soviet contact?) In Doherty’s thriller, Blunt swaps briefcases in Paddington Station with his contact and “marches cheerfully away.”

Under Stalin’s orders, did those drawings get sent to a camp in the gulag to be forged? Did those forgeries go back to Blunt? Are they in the Royal Collection today? If so, where are the real works of da Vinci? And what was the human cost of the project?

What happens to Pasha Kalmenov, the 19 other artists — including Victor, who has become his friend — and to the men who are guarding them?

Keep in mind another historical fact: On March 5, 1953, Stalin died. If this project is real, how did his death affect it?

Start reading The Leonardo Gulag and find out.

Author Doherty vividly describes the conditions under which Pasha and the others work: the crude huts heated by a stove, the meals of “watery cabbage shchi, hard bread, a single potato and some strips of dried meat.”

Doherty describes how, outside, after an artist falls face-first against a steel upright and is frozen to it, a single rifle shot delivers a “mercy” killing. Then, seeing the shreds of facial flesh and skin on the steel, Pasha mentally recites the facial muscles.

Then there’s the sexual pairings among the prisoners (Victor and one young woman, Irina, pair up) and the guards. Every few days, Bolostov, the camp commander, takes a young woman (often Irina) for his pleasure.

Also described:

- How pregnancies are dealt with: “by a female guard. She uses a kitchen skewer.”

- How the prisoners deal with body lice: They “spread their garments on dormitory stoves and listen with satisfaction to the cracking noises as the lice and eggs explode.”

- The Arctic blizzards called “burani” in which “the change in air pressure can be so sudden and savage that it drives breath from lungs” and can suffocate a person to death.

- The howling of wolves out on the vast and surrounding tundra. An escape from the camp that the guards don’t try to stop; why waste bullets when, soon enough, come screams as the escapees are torn apart by wolves?

In The Leonardo Gulag, Pasha Kalmenov understands escape is impossible. He keeps forging da Vinci’s drawings.

And the seasons pass. And then come the executions. Then more executions.

And The Leonardo Gulag races toward its startling conclusion.

Bold as Stalin’s forgery project, brilliant as Pasha who was forced into it and crackling as the ice under Bolostov’s truck, this thriller grips the reader in its icy grasp and plunges the reader deep into the lethal paranoia that was Stalin’s Russia. Will Pasha Kalmenov escape? Until the final page, the reader waits in suspense.

Pasha knows, “Draw as if your life depends on it.” Because it does.

For more on the author, visit his BookTrib profile page.