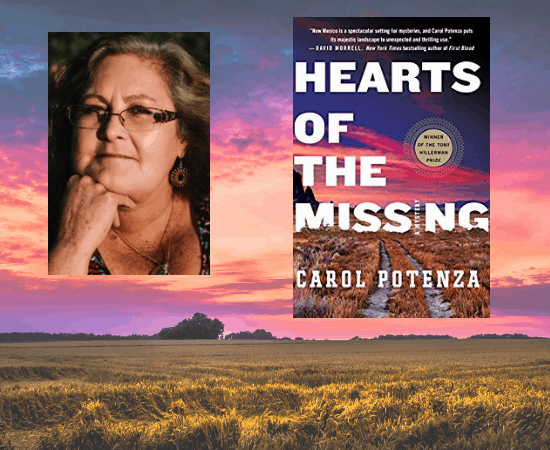

Hearts of the Missing by Carol Potenza

The spirit of Tony Hillerman hovers over every page of Carol Potenza’s debut novel Hearts of the Missing (Minotaur), so it’s no surprise that, when still unpublished, it won the 2017 Hillerman Prize for the best first mystery set in the Southwest.

Hillerman’s spirit is far from the only ghost that haunts it, however. The book features Nicky Matthews, a woman police sergeant for New Mexico’s Fire-Sky Pueblo, the Tsiba’ashi D’yini. She is also a Bureau of Indian Affairs-trained federal agent often brought in as a liaison with the Office of Medical Investigation on matters of cultural sensitivity.

But Nicky is not a Native. She is white, and she knows that her training is no replacement for all she has yet to learn. It’s a fact driven home forcefully for her the day she investigates a burglary at a local mini-mart and sees an old woman’s face in the window – not on the other side of the window, in the glass itself. And it’s the third time she’s seen it.

A traditionalist friend of hers explains: She’s meant to rescue someone — though she will have to hurry. That person is “either already dead or will be soon.”

It is the beginning of an extraordinary journey for her into ancient truths and very modern evil, through untracked territories of culture, science, vengeance, and greed, all in search of the “hearts of the missing.”

Much of the inspiration for the book came from Potenza’s sister-in-law, herself a police officer on a New Mexico pueblo.

“She is an expert on tribal law and sovereignty. She knows federal law, state law, she’s cross-commissioned so she can arrest non-Natives on pueblo lands. She has specialty training in gangs, forensics, sex offenders, artifact looting, and the list goes on.

Her knowledge has been indispensable. When I have questions about what to do if – for example – a person is reported missing, she knows the procedures, protocols, and programs to access. I ask her a huge range of questions, from how it feels to be shot at to how often she’s required to change passwords on her work computer.

The opening scene in the book is based on a mini-mart break-in she worked, down to sunglasses scattered on the floor and the surveillance video showing one of the perps swinging and bouncing a baseball bat off the window, and his buddy doubling over in laughter. But one thing I hadn’t really expected from her job that also made its way into the book was the hostility from some of the other officers. She’s so smart, she advanced faster on the job than many of the officers hired at the same time she was. Nicky experiences some of that same hostility in the book. Then there are my sister-in-law’s visions!”

Her visions!?

“Not just my sister-in-law! Three of my in-laws are what her eldest sister calls ‘sensitive.’ That sister sees out-of-the-corner-of-your-eye shades and shadows. Her brother ‘hears’ sounds from the past. He tells a story about working at a prison (he’s a nurse) where part of the building is unused. One night, while walking down the corridor of an old office area, he heard echoes of telephones ringing, the strike of manual typewriter keys, and low murmuring voices where you couldn’t quite make out the words. But no one was there.

The sister-in-law who gave me the inspiration for Nicky told me she’d never seen anything that could be considered supernatural until she started working on pueblo lands. I’ll tell you one story that made my hair stand on end. It was late at night and all of the officers were out on a call. My sister-in-law and one other officer were manning dispatch, coordinating personnel. The dispatch center had a long counter that faced a large picture window.

Outside the window, between buildings, was the wreckage of a car involved in a drunk driving crash. The passenger, a young woman, had been killed in the wreck a few weeks before, and the police decided they would tow it to the different schools as an example for the kids.

As my sister-in-law and the other officer sat staring into the darkness, a young woman slowly climbed out of the wreckage, inching her way around the crushed and twisted metal of the car doors. She straightened and began to walk directly toward them.

She was featureless, insubstantial, like walking smoke. ‘Do you see her?’ my sister-in-law whispered. ‘I see her,’ the other officer replied. They stayed frozen as she came closer and closer…and then she was gone. They believe it was the spirit of the woman who died in the car and, for some reason, waited until that night to leave.

But she’s not the only person on the pueblo with ghost stories. I recently went on a ride-along with one of the Native open space officers and he told me a story about a little boy who is seen bouncing a basketball late at night at the high school. When anyone approaches him, the basketball rolls off the court and he chases after it, only to fade away into the darkness.”

Such stories are why Potenza wanted to make Nicky white, an outsider: “I wrote what I knew. I wanted Nicky to have and experience some of the same misconceptions about Native Americans as non-Natives, so I could present and confront them in the book. For example, Nicky and Savannah (her best friend and a Native) have some great arguments about the differences in cultures, which gives me an opportunity to present both sides of an issue.

Initially, I wanted an outsider for practical reasons. It allowed me to slip cultural and traditional details from pueblo members to Nicky and the reader so I didn’t bog down the writing with swathes of backstory and narrative.

But outsider status ended up becoming a major theme in this book for Nicky and a number of other characters. For Nicky, it adds an emotional layer, because even though she cares for the people and has come to love the culture, her role is ancillary. That’s painful to her. There are walls Nicky knows she cannot breach.”

Besides, Potenza says she knew her own limitations: “I didn’t make Nicky Native American for the same reason Fire-Sky Pueblo is fictitious. Even though I’m a great believer in shared human experiences, I don’t know the pueblo cultures well enough to give Nicky the proper background.

My exposure to Native American cultures is extremely limited. I didn’t feel comfortable with the depth of knowledge I would need for the type of authenticity found in Tony and Anne Hillerman’s books. I felt that to write about a specific culture without a deeper context was almost an intrusion.”

Nevertheless, her research is clearly impressive. Her book is filled with details large and small about pueblo life and culture, down to the symbolism of stones in a piece of jewelry, the significance of a gate that will not close, and the fact that, out of respect, one should not meet an elder’s eyes for more than a few seconds. How did she go about the research?

“The gate story is true, by the way, except it was the door to a house.

Initially, my major source of research was my sister-in-law and her observations, but I want to be clear that when I would ask her for more invasive details about why this ceremony was done, or what the significance of a ritual meant, she would tell me she didn’t know because, as an outsider, she felt that it wasn’t her business.

Her response had a profound effect on how I wrote my protagonist. There is an actual scene in the book where Nicky is asked about the deeper significance of a ceremony and she replies just like my sister-in-law did – she’s never asked because it’s not her business. I had two readers for Hearts of the Missing from the pueblo culture – one was also Apache. I didn’t know about ‘sensitivity readers’ at the time – I just wanted to see how they felt about an outsider setting the book in pueblo culture, but they completely understood that this book was fiction.

One of my readers asked me to change a few things, and I did. If they agree, I’ll ask them and a few more friends I’ve made since the Hillerman Prize to read the second book in the series. As for wanting details forbidden to me because I’m an outsider, I can’t think of anything thus far. I want to maintain a distance so my protagonist stays distant, but it also has to do with a personal respect for cultural privacy. I’ll make do with what is shared.

I think one of the most interesting things I’ve seen is a ‘throw day.’ Many of the Feast Days celebrate certain Catholic saints. For example, Acoma Pueblo holds harvest dances and celebrates Saint Esteban over the Labor Day weekend. If you were named after that saint, your family gathers food, toys, candy, fruit – all sorts of things – and packs them into laundry baskets. They take the packed baskets to the plaza in the village holding the fiesta.

People gather below the plaza walls and the family literally throws the food and gifts to the crowd. You haven’t lived until you’ve seen a watermelon heaved skyward toward a tightly packed group of people! Or a gorgeous, fragile, handmade and traditionally painted pot. Your heart gets stuck in your throat as they spin into the air and drop toward dozens of outstretched arms. (Both the watermelon and the pot were caught without breakage.) My sister-in-law said she’s seen roof throws where bicycles are tossed into the crowd gathered in front of a house.”

One of the interesting things about the novel is that, for all the mysticism and lore, there is also a great deal of science. That comes from Potenza’s own background. She has a doctorate in biomedical sciences, and was a researcher at New Mexico State University before joining its department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

In her research life, “I was a plant genetic engineer and used molecular biology and tissue culture to manipulate genes in specific biochemical pathways. I worked with tobacco – a plant version of the lab rat – and alfalfa to find genes that were overexpressed with root-knot nematode infection, a devastating soil pest in crop plants.

I was never a principal investigator at NMSU – never had my own lab – so I knew at some point I’d have to find another avenue of work. I’d been teaching on and off in the Chemistry and Biochemistry department, and when they have a teaching faculty opening, I applied for the job. But teaching is not as immersive as research, and after a couple of years, I started to look for things to do with my free time outside work. I decided to write fiction!

I love the sparseness of Tony Hillerman’s writing and the way he evokes the southwest with so few words. One brief sentence and the reader is surrounded by a fiery New Mexico sunset or a freezing desert night. The first Margaret Coel book I read floored me with her description of a winter’s day right after human bones were found. I wanted to write like them.”

For pacing and action? “Thrillers by Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child. I love the way they write their protagonists into deadly corners and then pull them out over and over. Plus, I love the way they use science and technology as part of their plots. Because of all these authors, I was determined to mix southwestern murder mystery with science and add action-packed thrills throughout my books.”

The most important part of her writing process? “Three-by-five cards! They are all over the house, my office, my purse, tucked in books I’m reading, everywhere. I plot inside my head, and when I have an idea for a theme or scene or clue drop, I grab one of those ubiquitous cards and jot it down. I’m also a firm believer that almost every detail in my books has to have a plot purpose. If it’s there, it’s going to be important to the crime or the interpersonal relationships or a red herring. As I write forward, I’m always going back to earlier scenes to insert plot threads. Craig Johnson of Longmire fame wrote a blurb for the book that, in my mind, captures exactly what I’m trying to do: ‘Hearts of the Missing winds and weaves together like a Tsiba’ashi D’yini basket holding one fine mystery.’ I can’t tell you how pleased I was with that quote.”

She has been just as pleased with the rest of her publishing process so far: “It’s been extraordinarily smooth, which means I’m probably going to jinx myself right now. I started writing fiction only a couple of years before I finished Hearts. It was my third finished book, but the first murder mystery I wrote and the only book I ever seriously queried. It was rejected by a publishing house a few months before I entered it into the Hillerman Prize contest. The editor who selected it for the prize asked me to do some developmental edits that made the book about a thousand times better than the original submission.

I do want to get in a thank-you to my critique group at the time. Without them beating me over the head about my ‘amateur author tics,’ I don’t know if it ever would have been published.”

Next up is the second book with Nicky Matthews: “I’ve finished it – doing edits. I’m writing the third and I’m researching the fourth. All of the plots have that same blend of mystery, supernatural and science.”

And not only that: “There’s a major theme that will arc across four books! Many Native American cultures have a Clan system or kinship organization so they won’t intermarry. The Fire-Sky Pueblo has four fictional ‘Elemental Clans,’ each associated with a stone used in jewelry. These Elemental Clans are Earth (onyx), Sky (turquoise), Fire (coral), and Water (mother of pearl). Hearts of the Missing’s theme is ‘Earth’ because of the sacred caves on Scalding Peak (a fictional stand-in for Mt. Taylor). The second book is themed ‘fire,’ the third, ‘water,’ and the fourth, ‘air’ or ‘sky.’ Those ‘elements’ will appear prominently in each book.”

It’s clear that Potenza has her own clear visions for what she should be writing, and how – and that the spirit of Tony Hillerman must be smiling.

Hearts of the Missing is now available for purchase.

Buy this Book!

Amazon