Among the array of photographs in Grace Kennan Warnecke’s new memoir is a picture of her standing with Ted Kennedy and his family in Leonid Brezhnev’s office. “The trip was highly unusual – and I knew it at the time,” recalls Warnecke.

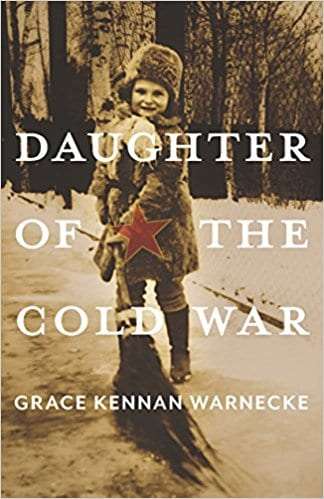

Warnecke calling something unusual? How unusual, given a life lived so close to one historical moment after another and captured in detail in her work, Daughter of the Cold War (Russian and Eastern European Studies, University of Pittsburgh Press), released today.

Chatting with Warnecke reminds me of how arduous a path it has been for women. When she describes her mother at home and her father, George Kennan, as one of the most important diplomats of the 20th century, we appreciate how early on her social skills were honed and that she was surrounded by famous people.

In the memoir, in which she chronicles her many brushes on the international diplomacy stage and with world leaders, the author views herself as both sheltered and hidden as a daughter (eldest child), wife and finally as a mother – yet, not in terms of her hard-earned accomplishments.

Grace Kennan Warnecke’s story is one an awakening, a challenge that required many years of soul searching and self-discovery. She has been Chair of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy, Fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, filmmaker and critic. Her impressive career is proof of her perseverance.

She thoughtfully answered my questions below.

Susan Shapiro Barash: In the prologue, we learn that this book is a significant step for you. How would you describe the writing process and how did it affect you? Were there any surprises along the way?

Grace Kennan Warnecke: The writing process took over eight years, but began 10 years ago when I was in a writing group at the 92nd Street Y with Veronica Golos as our teacher. The class was called Memoir from the Middle, about having more experience in life. Over the years, five of us continued to meet and really took advantage of the course. Eventually, we met in my apartment and I’m the third person [in the group] to have a book published. It was the useful, helpful criticism that kept us going.

SSB: From the start, we learn of your attachment to your father and your hesitancy in terms of his perception of you. Do you feel that as the eldest of four and as a first-born daughter, your relationship was overshadowed by sexism and the cultural expectations of women at the time?

GKW: I do feel my father had an old-fashioned view of women. They were charming, gracious, beautiful, but not to be in the professional world. He was surprised at what I was doing because of this. He had great gifts and this made me feel slightly inferior. I do feel I earned his respect. But while I was very successful in Ukraine, I was horrified when he suggested that I could be the social secretary in Moscow. Still, I believe he admired what I was doing in Ukraine and that I was living there.

SSB: Your portrayal of your mother shows us a complicated woman who sacrificed a great deal for her husband and family. To add to this, you write that you were embarrassed that she was giving birth while you were in your second year in college. When and how did you come to terms with your relationship with her?

GKW: As time went on, my mother became a better mother. When I was born, she was only 21. She hardly knew my father and was trying to get to know him. And my father and I were so close that she might have had a certain kind of jealousy over it. So while she wasn’t a great mother when I was young, our relationship was warm as time went on.

SSB: It is an interesting detail that you ended up as an undergraduate at Radcliffe/Harvard after being turned down by Middlebury College. Do you believe that being a graduate was an imprimatur and gave you standing in certain circles?

GKW: Yes. I had a wonderful education. I’m thrilled that I went there. At the time, I was crushed by being rejected by Middlebury, but it was an early lesson in dealing with rejection.

SSB: When you describe your broken first engagement, your marriage to C.K. McClatchy and the divorce that followed, the reader senses that you were young, inexperienced and unsupported. In particular, your mother’s need for you to keep the marriage to McClatchy intact had to be difficult. How did this contribute to your decision to marry to Jack Warnecke?

GKW: I came out of one kind of marriage and wanted another kind. The first marriage was cold, and my new husband had passion and a big reputation – he was creative. He was very controlling, but also very attractive. He was famous and that was important. I went toward men of that ilk. Still, the second marriage was a mistake. He had four children, I had three and he wasn’t supportive of mine. Although he asked me to stay, we had very different values. Shared values are very important in a relationship, and it was time to leave.

SSB: Against the setbacks and struggles, you have had great fortitude throughout your life. To what do you owe this ability and who were your role models?

GKW: I don’t know if I had role models as much as I had no alternatives. At the age of 10, I was sent to boarding school and there was no way to communicate with my parents. This was a very different time from today where there are ways to stay in touch. I was on my own. Again, in the eighth grade I was far from my parents who were in Moscow, and I couldn’t be in contact. I had to know how to take care of myself.

SSB: As you set out to write this memoir, did you read the works of other memoirists? Whose work did you find touching and perhaps a template for the kind of honesty and reveal that is in your book?

GKW: I have read all of my life, and am a constant reader. My mother only wanted me to take out five books a week from the library when I was younger, and I wanted more. I have read lots of memoirs – along with fiction and non-fiction. While writing my own memoir, I was fortunate to have the letters that I’d written my parents. They kept them all, and also I had the letters that I’d written to my Aunt Connie. This trove of letters had the honesty of the actual times.

From Warnecke’s memoir, with Ted Kennedy’s family in Brezhnev’s office.

SSB: Although your ascension into your professional sphere occurred decades ago, what words of wisdom would you offer younger women who seek a career similar to yours, holding positions in the public and private sector?

GKW: I would recommend never saying no. Accept the interesting challenges and try things that are new. If possible, have a skill. My skill was speaking the Russian language. I also had the ability to keep going and the need to work. Even when I was married, I wanted to work. When I was married the first time, I wrote translations for the Library of Congress. I always wanted to do something. I did volunteer work, too, because I wanted to be involved. And, I had this strong feeling about the arts – I was interested in all of the arts.

SSB: Your consulting company in Russia and your knowledge as a Russian specialist are quite striking. What caused you to still underestimate your father’s pride in your undertakings?

GKW: None of the women in my family worked. My father’s view of women was that they got married and had children. I was a dreamy child, a messy child, happier reading. I knew there was nothing serious in terms of work for women. That is the feeling that surrounded me.

SSB: Do you feel you are at peace with certain relationships and decisions? How has this played out for you and what caused your level of acceptance?

GKW: Yes, I am at peace. My writing group has been extremely supportive. I have learned from other people, from groups of women. I could not have done it all by myself. It kind of fits together and I’m thrilled to have written this book, and hope that people get something out of it. Both women and men, because it is an adventure story and not only a woman’s book.

***

Courtesy of the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Grace Kennan Warnecke has had an extraordinary career as an NGO leader, small business development expert, writer and photographer. She was senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in 2013. She served as country director for Winrock International in Kyiv, Ukraine from 1999 – 2003 as well as director of the Women’s Economic Empowerment project. Grace is also the founder and project supervisor of the Volkhov International Small Business Incubator, Russia; executive vice president of the Alliance of American and Russian Women. She was associate producer of a PBS documentary, “The First Fifty Years: Reflections on U.S.-Soviet Relations,” winner of the Alfred I. Dupont Columbia University Award. She attended School No. 131 in Moscow, among others, and is a graduate of Radcliffe College where she majored in Russian history and literature.