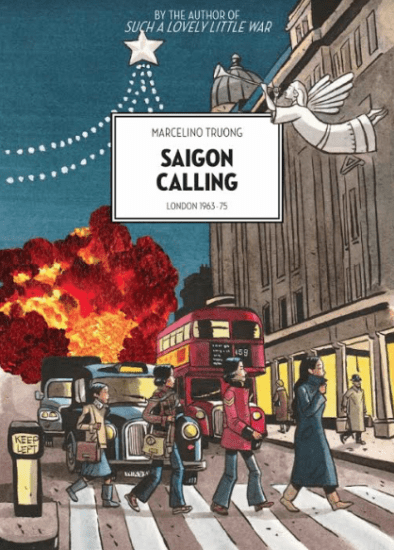

Saigon Calling by Marcelino Truong

BookTrib: You’re a self-taught illustrator, and the images you have in both graphic novels are very particular, and sometimes deal with very heavy subject matter, which is reminiscent of MAUS. Did your artistic abilities grow organically in the media of drawing for graphic novels, or did you start off drawing, or designing somewhere else first?

Marcelino Truong: Both my graphic novels are the result of many years of experience as a self-taught illustrator working for both the publishing world and the press, and sometimes other medias such as animated motion films or advertising. I started off as an illustrator in 1983, aged 25, with an MA in Political Science and an MA in English Literature.

I learned my trade at the job, illustrating fiction or documentary books for young readers, designing book cover images, producing illustrations for newspapers and magazines in France such as the progressive daily Libération. I published three comic art albums in the midst of all that, but often refrained from launching into a comic art book for lack of a good scenario.

That is how I slowly and painstakingly acquired the speed, the confidence, the versatility and the endurance that are necessary to produce a graphic novel. It took me a while to get there!

BT: In Saigon Calling: London, you have images of your mother when she suffered from post-partum depression and bipolar disorder. These are still considered pretty taboo topics: can you tell us a little bit about that?

BT: In Saigon Calling: London, you have images of your mother when she suffered from post-partum depression and bipolar disorder. These are still considered pretty taboo topics: can you tell us a little bit about that?

MT: My mother suffered from a bipolar disorder which was revealed at my birth, when she suffered a spectacular postpartum-depression. At my birth in 1957, at the American hospital in Manilla, my mother was thought to have lost her mind and she subsequently spent a full month in a psychiatric hospital. Later on, during her whole life, she was subject to episodes of heavy bipolar disorder. Her mood swings hung like a sword of Damocles above our heads for as long as I can recall.

In those days, manic depression was rather taboo. Even in the home, there was a form of denial going on. It wasn’t until quite late in life that I learned about manic depression. Until then there had never been any real discussion at home about the reason for Mum’s mood swings. Moreover she would have been the last person to talk about them, although she was heavily medicated for anxiety, nervousness, depression. My mother was a very nice person, but her disposition could change suddenly under fatigue or stress and she could become very difficult.

I thought it was necessary not to brush this under the carpet, when writing both my graphic novels, as this was the backdrop of my youth. Many people, as I learned later, have had their lives affected by manic depression in their intimate circle, and so I believe it wise not to pull a veil over this matter.

BT: One of the things that comes across clearly is that the news of what is happening in Vietnam is all from the media and the press. In today’s time, the veracity of the press is something that it continually being called into question, no matter what political side someone is on. Do you see any echoes of the media then in the media we have now?

MT: During the Vietnam War, the media coverage of the war was very extensive, but it was unbalanced. While there were hundreds of foreign correspondants working freely and unrestrained in South Vietnam, there were but a chosen few of progressive journalists or photographers allowed to function in communist North Vietnam. So I do not question the veracity of the press when it was working in South Vietnam, and we were constantly flooded with information, much of it disturbing, during the whole war.

However the reportages coming from the handful of foreign reporters who had been admitted by the communist authorities in Hanoi, after minute scrutiny of their political orientation, were of questionable veracity. Indeed, Hanoi only let in foreign progressives who held positive views of the regime and who would show it in a good light. Many of these reporters had covered the liberation revolutions in Cuba or in North-Africa and were anti-imperialists at heart. And so these observers tended to be lenient and always strived to show the North Vietnamese totalitarian state under a positive light. Surprisingly, the reports coming from these journalists working under discreet but real supervision from the Hanoi authorities were not viewed with sufficient discrimination when published in the West.

In the 60s and 70s, and during the Cold War, many well-intentioned foreign reporters were blinded by their anti-imperialist faith. America was seen as the arch imperialist state, whereas Third-world liberation movements were looked upon with sometimes amounted to excessive complacency.

It is possible that the same thing is going on today. Sometimes, we receive supposedly objective reports that have been written by journalists with marked political opinions. Sometimes these biased reports are sold to us as objective reporting.

BT: I feel like both of these graphic novels together are so comprehensive, not only of your life growing up, but also of what it was like during that time, and the war. Is there anything you didn’t add in, or something you wanted to add, but ultimately chose not to?

MT: There are lots of things I would’ve liked to add, but wasn’t able to for lack of space. Thousands of books have been written about the Vietnam war and so this is impossible to cover the many aspects of that war in one book. You can’t say it all in one book. Perhaps it’s better that way.

During the writing process, there were many stories told to me by Vietnamese friends who had lived throughout the events until 1975 and sometimes later, that I would’ve wanted to include, but this was not possible. However, I hope to tell some of theses stories in another graphic novel that I intend to publish directly in English with the help of Arsenal Pulp Press.

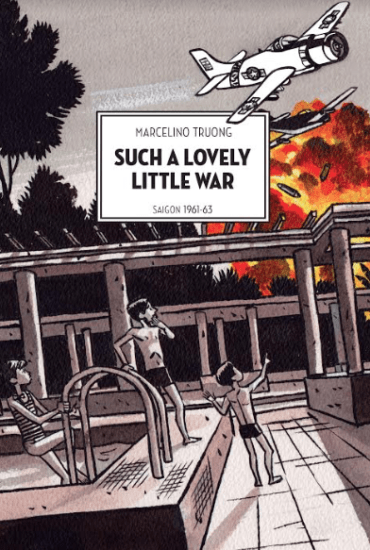

BT: Your two books Such a Lovely Little War: Saigon 1961-63, in 2016, and Saigon Calling: London 1963-75 were published in 2017. Did you originally plan them out as a series, and if so, can we expect to see more?

BT: Your two books Such a Lovely Little War: Saigon 1961-63, in 2016, and Saigon Calling: London 1963-75 were published in 2017. Did you originally plan them out as a series, and if so, can we expect to see more?

MT: Originally, my two graphic novels were not planned as a series. It is only after the success of the first one that my French publisher suggested I write a second opus.

I had thought of writing a third volume in which I would’ve described postwar Vietnam, as observed in my Vietnamese family, but instead I have chosen to work on a fiction this time.

I have begun to work on a graphic novel about the end of the French Indochina war (1945-54), observed from the Vietnamese communist side. We will follow the picaresque adventures of a young Vietnamese artist from Hanoi who enrolls into the People’s Army. We will tramp in his footsteps on the costly march to victory and then experience some of the disillusions which followed the communist victory.

I am working on the scenario right now and hope to publish the graphic novel by the end of 2018 or early 2019.

Buy this Book!

Amazon