Allegiance by Kermit Roosevelt III

We live in an era when a 14-year-old whiz-kid who brought a clock to school on his own was rewarded for his hunger for learning by being hauled away in handcuffs. Why? Because he’s a Muslim, and his teacher, who assumes the clock must be a bomb, calls the police.

Aren’t we better than this? How can something like this happen in America?

That incident should be of no surprise to those who know this country’s history—because victimizing people based on their ethnic heritage has happened here before. During World War II, between 110,000 and 120,000 Americans of Japanese heritage were place in internment camps, solely on the basis of their ethnicity. While the Greatest Generation was fighting for freedom and overseas, the personal liberties of tens of thousands of Japanese Americans were being systematically abused by the United States Government.

That incident should be of no surprise to those who know this country’s history—because victimizing people based on their ethnic heritage has happened here before. During World War II, between 110,000 and 120,000 Americans of Japanese heritage were place in internment camps, solely on the basis of their ethnicity. While the Greatest Generation was fighting for freedom and overseas, the personal liberties of tens of thousands of Japanese Americans were being systematically abused by the United States Government.

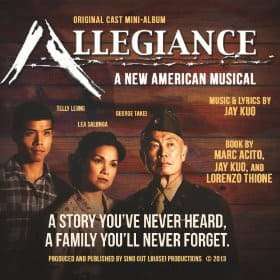

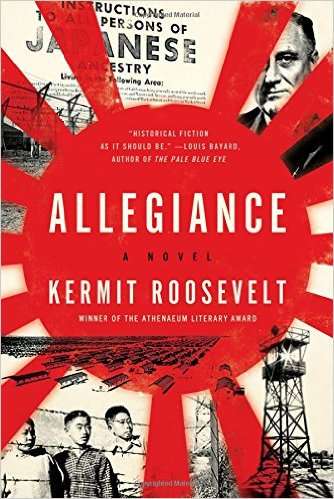

As America confronts its ongoing struggle with racial and ethnic prejudice, the internment scandal is being re-examined. This fall, George Takei (best known as Star Trek’s Mr. Sulu) brings the story of his own internment as a child to Broadway in the musical Allegiance. And now, a novel of the same name is being released by author Kermit Roosevelt III (great-great-grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt, and cousin of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the president who signed the internment order).

The novel Allegiance (Regan Arts, 2015) is a murder mystery about governmental abuse of power, corporate greed and political influence, and an idealistic young lawyer trying to do what’s right. Roosevelt, himself a lawyer who once clerked for Supreme Court Justice David Souter, once believed his government could do no wrong, but he became disillusioned after 9/11. How much of Allegiance is true? “Everything except the murder,” Roosevelt says. “And it can happen again.”

The novel Allegiance (Regan Arts, 2015) is a murder mystery about governmental abuse of power, corporate greed and political influence, and an idealistic young lawyer trying to do what’s right. Roosevelt, himself a lawyer who once clerked for Supreme Court Justice David Souter, once believed his government could do no wrong, but he became disillusioned after 9/11. How much of Allegiance is true? “Everything except the murder,” Roosevelt says. “And it can happen again.”

BookTrib chatted with Roosevelt about his book, the themes it addresses, and his familial role in the story.

BT: Allegiance examines the demonization of innocent people based on their ethnicity. To what extent did you intend to make this a cautionary tale, given the post-9/11 mood of our country today?

KR: It’s very much intended as a cautionary tale. Over and over again, usually—but not always—in wartime, we react out of fear. We overreact; we hurt innocent people. Later we regret it. We say it won’t happen again…but it does. There are several different dynamics at work, but one very important one is this: It’s often very hard to tell the dangerous people from the trustworthy ones. And when there’s a lot of pressure to get the bad guys, we often don’t succeed in identifying the dangerous people. Instead we get the people who are different—certainly if they’re different in a way that makes them look like the enemy. A lot of what we’ve done in the aftermath of September 11 fits this pattern. With just a couple of exceptions, the people we’ve hurt haven’t been Americans, which makes it a bit different, but just this July, former Democratic presidential candidate Wesley Clark suggested that “disloyal Americans” should be put in camps for the duration of the war on terror.

BT: Much of Allegiance has to do with corporate influence on the government. Give us your thoughts about corporate influence not only on the government today, but on the press.

KR: Corporate influence on the government is very troubling. One of the things that frequently goes along with our unfortunate overreactions is corporate opportunism. The removal and detention of Japanese Americans was driven in part by sincere, though unfounded, fears about their loyalty, and in part by racism, but also in part by a desire on the part of California fruit growers to eliminate the competition of Japanese-American farms. Our invasion of Iraq was enormously profitable for various military contractors. The government paid tens of millions of dollars to a pair of psychologists to design an enhanced interrogation program. Most of the time, we look back on with regret [that they] are going on, someone is getting rich from them.

Corporate ownership of the media is perhaps even worse. The media has a crucial role to play in our democracy—we rely on media to give the American people the information that’s necessary for us to govern ourselves and to monitor the performance of our elected officials. But if that role is being sacrificed because of corporate interests, it strikes at the heart of democracy.

BT: You’re in a unique position of being related to a central figure of this historical novel. How did that familial connection affect your writing of Allegiance?

KR: It affected the writing in a couple of ways. I feel affection for FDR—I think he was a great president. And part of the point of telling this story was to show that even good people can do bad things, that you can’t always trust someone because they seem like the right sort of person. That was FDR’s mistake, in my view: he trusted the generals and War Department officials who were like him, even though they were giving bad advice. So I felt like saying this about a member of my family might be an effective way to make the point.

More generally, I think that my ancestors have given me probably a greater than typical sense of identification with the government. I think we should all identify with the government to some extent. It’s a democracy; the government acts in our name, and we bear some responsibility for what it does. But I did, and still do, probably feel that identification a little more.

Which made it especially painful for me to see the government doing things I thought were misguided, doing things I thought were wrong. That pain is something I tried to express in the book; it’s something my narrator also feels. It’s a sort of wounded patriotism, because I think it’s also important to understand that the government is not America. The government can do bad things—that doesn’t mean we’re a bad country. But it does mean that we the people need to stand up and say, “That’s not my America. My America doesn’t do these things.”

And we can get better; we can learn from the past. The story of America is a story of progress, it’s a story of hope, and that’s also the story I try to tell.

Buy this Book!

Amazon