Small Victories: Spotting Improbable Moments of Grace by Anne Lamott

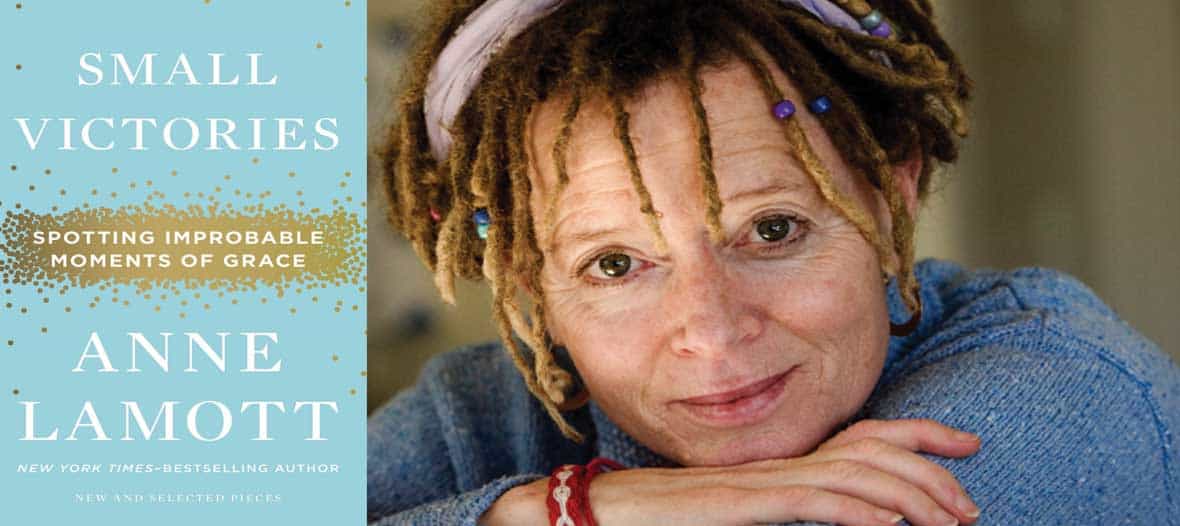

Anne Lamott has become known for her ability to write about such diverse topics as becoming a single mother after recovering from addiction, her son as a teenaged father, the craft of writing, and her faith with openness, grace and self-deprecating humor. In the 35 years since her first book was published, Lamott—a winner of the Guggenheim Fellowship and an inductee to California’s Hall of Fame—has become one of America’s most beloved and celebrated writers.

Her newest book, a collection of essays titled Small Victories: Spotting Improbable Moments of Grace (Riverhead, 2014) offers a message of hope and stories of triumph over hardship. BookTrib sat down with Lamott recently to discuss her views on the forgiveness and grief, which underscore the victories she describes in the book.

BookTrib: Readers might be surprised that a book that deals with difficult topics like terminal cancer or childhood disease is called Small Victories. How would you describe the collection?

Anne Lamott: I really had a vision of this book being about victory laps. About the miracle of people living through and rising back up after coming through the end of the world: the loss of someone they couldn’t bear to live without or a collective tragedy.

BT: Though you are Christian, and your faith plays a large role in your writing, your message to people living through such tragedies is different than the standard Christian message of surrendering to God. Why is that?

AL: I think that if someone is really suffering and scared and lost, for someone else to come up and give him some happy horseshit about silver linings, or to say that God never gives you more than you can handle—it’s not true. You see people in your own life who have been given more than they can handle, who’ve been given more than anyone should handle. It’s the same way when people say, “Let go and let God.” To me it’s just abusive to say that to someone who is really struggling, because it suggests that the person didn’t remember that. It’s like, if I could let go and let God take over in this circumstance, believe me I would, but I’m not going to just because you’re trying to shame me into having a different feeling than the one I’m having. The way I’m going to heal it is by talking about it and revealing it and having people share their equivalents with me. Hearing me is healing. It’s not going to be on some bumper sticker. So I find bumper sticker theology just infuriating.

BT: Forgiveness is a central theme in this collection. In several of the essays you write about how difficult it is for you, which I think many of your readers can identify with. Why do you think forgiveness is so difficult?

AL: There’s a lot more to not forgiving. Resentment and feeling victimized can create a lot of adrenalin. If you are feeling small and powerless and you get yourself whipped up into a lather of feeling wronged, it’s heat, and energy, and adrenalin. And that’s very mood altering. It’s a very powerful feeling to not forgive someone, because you do feel morally superior.

Forgiveness is a radical act. It doesn’t come naturally and it sure doesn’t come easily. Forgiveness is so painful because for me to forgive you I have to re-experience what you did to me. I have to really feel it again. It was already bad enough the first time that a wall went up, and so then to experience it a second time because I want to get free of the burden and the toxicity of not forgiving means I have to go through it all over again.

BT: The essays also deal with grief, which is another thing you have said you weren’t taught to deal with as a child. What do you know now about grief that you wish you’d known when you were younger?

AL: What I wish more than anything is that I had known that everybody—all children and really all humans—are in the same boat. Instead I was always told that I was just too sensitive, and I’d be much happier if I wasn’t the exact way I was. It was very shaming. My parents were very hip, very liberal. They weren’t abusive or anything like that. But in my house if you cried or got angry you went to your room, you didn’t have dinner.

I wish I’d known that it’s hard to be here, it’s hard to be part of a community, it’s hard to be in our own isolation and in our own minds, and everyone is troubled. There’s the cliché that we compare our insides to other people’s outsides, and I just grew up doing that and thinking that other people’s outsides looked so enviable. But once you get to know people, it turns out that everyone has the same challenges. Relationships are hard, children are hard, parents getting older is hard, people dying is excruciating. Finding your way, finding meaning, finding your path—it’s just hard.

Buy this Book!

Amazon