Becoming Josephine by Heather Webb

When men write the history, how do women fare? In Josephine Bonaparte’s case, not very well, says author Heather Webb. In researching Becoming Josephine, her novel about the first Empress of the French, Webb read a number of male-generated tales of the Revolution-era femme fatale that she found incredulous—and far from flattering. Here is a sampling:

When men write the history, how do women fare? In Josephine Bonaparte’s case, not very well, says author Heather Webb. In researching Becoming Josephine, her novel about the first Empress of the French, Webb read a number of male-generated tales of the Revolution-era femme fatale that she found incredulous—and far from flattering. Here is a sampling:

She danced “nearly naked” for her wealthy powerful lover Paul Barras after political meetings that, at the stroke of midnight, became wild sexual orgies.

When after 14 years of marriage, Napoleon told her they must divorce because he needed a male heir, Josephine screamed uncontrollably, then fainted.

One month after Napoleon’s defeat and exile in 1814, Josephine died—of a broken heart.

When Napoleon heard of her death, he told a friend, “I truly loved my Josephine, but I did not respect her.”

“Who wrote this down?” Webb says, laughing. “Who made this up? I don’t know.” The only given, she says, is that the chroniclers of the era were men, most of whom, if they’d ever met Josephine, surely wanted to make love to her. Her exotic accent, a legacy of her upbringing in Martinique; her seductive, slow, hip-swaying walk; her expensive wardrobe, always at the height of fashion, and her sexual prowess combined to make Josephine Bonaparte, neé Rose de Beauharnais, the most desired woman in Paris.

“Who wrote this down?” Webb says, laughing. “Who made this up? I don’t know.” The only given, she says, is that the chroniclers of the era were men, most of whom, if they’d ever met Josephine, surely wanted to make love to her. Her exotic accent, a legacy of her upbringing in Martinique; her seductive, slow, hip-swaying walk; her expensive wardrobe, always at the height of fashion, and her sexual prowess combined to make Josephine Bonaparte, neé Rose de Beauharnais, the most desired woman in Paris.

But her life wasn’t all parties, passion, and shopping sprees. Abandoned by her first husband, the aristocrat-turned-patriot Alexandre de Beauharnais, Josephine struggled with little support to provide for herself and her two children. To do so at the turn of the 19th century meant attaching herself to a man—in her case, the most powerful, moneyed men in her world.

Her lovers included General Louis Lazare Hoche, whom she befriended in prison during the Revolution, the specter of the guillotine hanging literally over both their heads; Paul Barras, one of the most powerful men in post-Revolutionary France, known for his decadent lifestyle; Lt. Hippolyte Charles, a witty Southern officer rumored to be a partner with Josephine in her business as a dealer of military supplies; and Napoleon Bonaparte, a greasy-haired, scabies-infected, socially awkward general who fell madly in love with her.

Her lovers included General Louis Lazare Hoche, whom she befriended in prison during the Revolution, the specter of the guillotine hanging literally over both their heads; Paul Barras, one of the most powerful men in post-Revolutionary France, known for his decadent lifestyle; Lt. Hippolyte Charles, a witty Southern officer rumored to be a partner with Josephine in her business as a dealer of military supplies; and Napoleon Bonaparte, a greasy-haired, scabies-infected, socially awkward general who fell madly in love with her.

The years surrounding the French Revolution, tumultuous, treacherous and full of uncertainty, inspired a live-for-the-moment attitude among many. “The times were insane,” Webb says. “Everybody was sleeping with everybody. Everyone was getting divorced. They’d get married and divorced in the same month. If you don’t know if you’re going to die the next day, it’s, ‘What the hell! Let’s get drunk on champagne and have sex.’ ”

The problem, for Webb, is that journalists of the time, as well as historians, biographers, and even some novelists, portray Josephine as a promiscuous, decadent, overly emotional shopaholic, exaggerating these aspects of her personality while ignoring her many admirable traits including resilience, intelligence, strength, and generosity.

“She was so adaptable,” Webb says. “The woman went from a provincial, rundown plantation to an aristocratic home, and then went through incredible, turbulent times, from one household to the next—people were being beheaded!—and was in prison. And somehow she always had friends, and always knew how to say the right thing. She paid attention. She was brilliant, I think, at reading people and the situation, and doing what she needed to do to survive.”

Her marriage to Napoleon was no different. In Becoming Josephine, she tells the general that she doesn’t love him, but consents to marriage for financial security for herself and her children. He, on the other hand, was smitten, judging from the ardent letters he wrote to her while in Italy shortly after their wedding.

And yet, no love letters from Josephine to Napoleon have ever been found. It’s possible that she never wrote any, for in his absence she fell in love with Lt. Charles. News of their affair reached her husband, and he flew into a rage. The couple reconciled and she ended the affair, but Napoleon’s subsequent letters are far less passionate. Soon he began his own numerous liaisons. And for which, Webb points out, he suffered neither censure nor winking ridicule, as Josephine did.

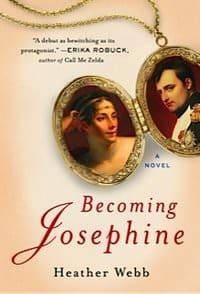

Webb set out to write her book in part, she says, to redeem the empress, who was so well loved that her admirers streamed past her chateau, Malmaison, for months after Napoleon’s remarriage. He put a stop to the pilgrimages out of respect for his new empress, but he continued to visit Josephine until she died. Not of heartbreak, Webb maintains, but of pneumonia.

Webb set out to write her book in part, she says, to redeem the empress, who was so well loved that her admirers streamed past her chateau, Malmaison, for months after Napoleon’s remarriage. He put a stop to the pilgrimages out of respect for his new empress, but he continued to visit Josephine until she died. Not of heartbreak, Webb maintains, but of pneumonia.

For Webb, a poignant message of “finding hope in starting over” emerges from Josephine’s life story. Her never-say-die attitude enabled her to rise, phoenix-like, from near destitution again and again to not only survive, but to thrive.

“When you look at…the way she beat odds and survived and switched situations to her benefit, there hasn’t been enough emphasis on those aspects of her personality We’re not one-dimensional; we’re multi-faceted people. I wanted to focus on those aspects of her personality.”

And in fact, Josephine herself may have wanted this book. Webb says the empress came to her in a dream, long before the French teacher had ever written anything. Webb awoke from that dream and “I definitely felt spiritually connected,” she says. “Her voice was in my head almost instantly. It was immediate.”

And in fact, Josephine herself may have wanted this book. Webb says the empress came to her in a dream, long before the French teacher had ever written anything. Webb awoke from that dream and “I definitely felt spiritually connected,” she says. “Her voice was in my head almost instantly. It was immediate.”

As for Napoleon’s “loved her, but didn’t respect her” comment? Webb is skeptical. After Josephine died, her ex-husband returned to Malmaison, it’s said, and gathered violets, whose scent she’d adored, from her garden. He wore them in a locket next to his heart until his own death, in 1821. “He loved her,” Webb says. “Because he was sentimental, at the end of it all.”

Image Credits:

Josephine and Napoleon portraits: National Gallery of Victoria (http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/)

Malmaison: www.paris-tour-guides.com

Buy this Book!

Amazon

Interviewing Heather Webb was a pure delight! Thanks to Book Trib for the opportunity.