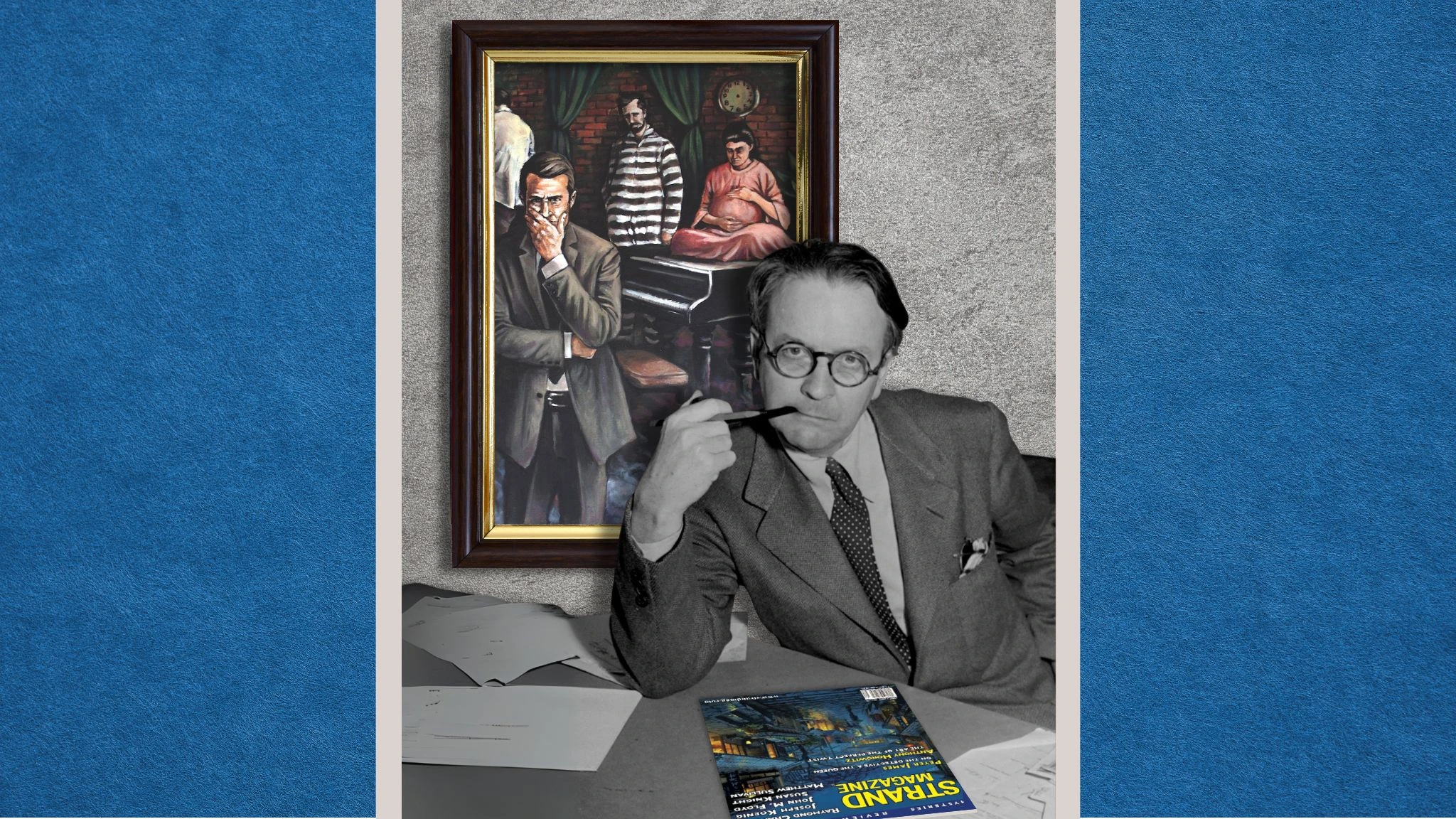

In the history of American noir, Raymond Chandler looms like a figure caught in a shaft of streetlight — sharp suit, sharper sentences and even sharper wit. In his novels, the creator of hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe gives us dark, seedy cityscapes full of corruption, vice and wisecracking loners whose dialogue snaps like the crack of a match. But what happens when Chandler himself, not his iconic private eye, is the one trapped in the shadows?

That question is at the heart of “Nightmare,” an unpublished essay by Chandler that has lain hidden for decades — until now. Discovered in the archive of Chandler’s longtime secretary Jean Vounder-Davis, purchased at Doyle Auctions, authenticated and released with the permission of the Chandler Estate, the piece has just been published for the first time in the pages of The Strand Magazine.

In “Nightmare,” Chandler imagines himself awaiting execution in a prison cell. The piece is brief — only a few hundred words — but in its taut, dreamlike tension, it carries all the hallmarks of his prose: the vintage turns of phrase, the unsettling atmosphere, the uncanny ability to conjure an entire world in a single vignette. “It’s like Chandler walking into the Twilight Zone,” says Andrew Gulli, managing editor of The Strand, who tracked down and purchased the manuscript.

To heighten the unease, The Strand has paired Chandler’s words with full-page oil paintings by artist Jeffrey B. McKeever. The illustrations echo the essay’s darkest images, translating Chandler’s nightmare into bold, noir-infused scenes. The result is less an essay than an experience — a collaboration across time between Chandler’s imagination and McKeever’s brush.

Chandler Without Marlowe

For readers who know Chandler mainly through The Big Sleep or The Long Goodbye, what’s most striking here is the absence of Philip Marlowe. There is no gumshoe wisecracking his way through danger, no dogged investigation leading to a crooked truth. Instead, Chandler himself is the protagonist — and he is powerless. “Instead of fighting his way out of a mess, he’s kind of resigned to his fate,” says Gulli.

That reversal is what makes “Nightmare” so haunting. For decades, Chandler’s fiction has represented control: the detective navigating chaos, never entirely safe but always armed with wit and resilience. Here, we glimpse the opposite. The essay reveals a writer willing to expose the fragility beneath the hard-boiled mask — the insecurities and fears that even literary idols carry.

“It does show that for all the notions we have that Chandler was this king of confidence and success, that he was very human,” Gulli reflects. “He had his insecurities, struggles and fears. From working with authors for 25 years, the more you know authors, the more you realize that no matter how many books they sell, putting your work out there is something that can bring insecurities to anyone.”

A Strand Tradition of Discovery

The unearthing of “Nightmare” continues a long tradition at The Strand, which has previously brought to light unpublished works by mystery masters Agatha Christie, Truman Capote, and James M. Cain, along with iconic American authors Tennessee Williams, John Steinbeck, Rod Serling, Ernest Hemingway, Shirley Jackson and Louisa May Alcott.

But Chandler holds a special place in Gulli’s imagination. “We’ve published Chandler a record five times,” he says, a collection that includes other surprising sides to the master craftsman, including a heartbreaking poem and two playful letters. But for Gulli, “Nightmare” is by far Chandler’s most tantalizing work published by The Strand. “It captures something surreal,” he says. “Most times you know a person better by studying their fears than their triumphs.”

What makes “Nightmare” more than a curiosity is precisely this vulnerability. Chandler’s detective novels built an enduring myth of toughness and moral clarity. But in this brief essay, written like a fevered dream, we see something raw: Chandler stripped of Marlowe’s trench coat and revolver, facing mortality with dread rather than bravado.

The Significance of a Nightmare

That glimpse matters because it reminds us that behind every iconic character stands a writer grappling with his own shadows. Chandler’s nightmare may be unsettling, but it also makes him more human, his genius more poignant. And perhaps that’s the truest legacy of noir — not the illusion of invincibility, but the stark honesty of fear revealed in the dark.

For Gulli, the discovery carries a personal resonance. “Chandler is a literary idol,” he says. Not only did Chandler elevate dime-store pulp into literature, but he has also stood the test of time. “It’s a testament to his brilliance that we’re talking about him decades after he passed away. As a kid, I used to watch Powers Boothe playing Marlowe — little did I know we’d be publishing Chandler!”

That sense of awe infuses The Strand’s presentation of “Nightmare.” Released this week, the issue is already in bookstores and on its way to subscribers, offering the public a chance to step into Chandler’s darker imagination. Nonsubscribers can purchase the issue directly from The Strand here.