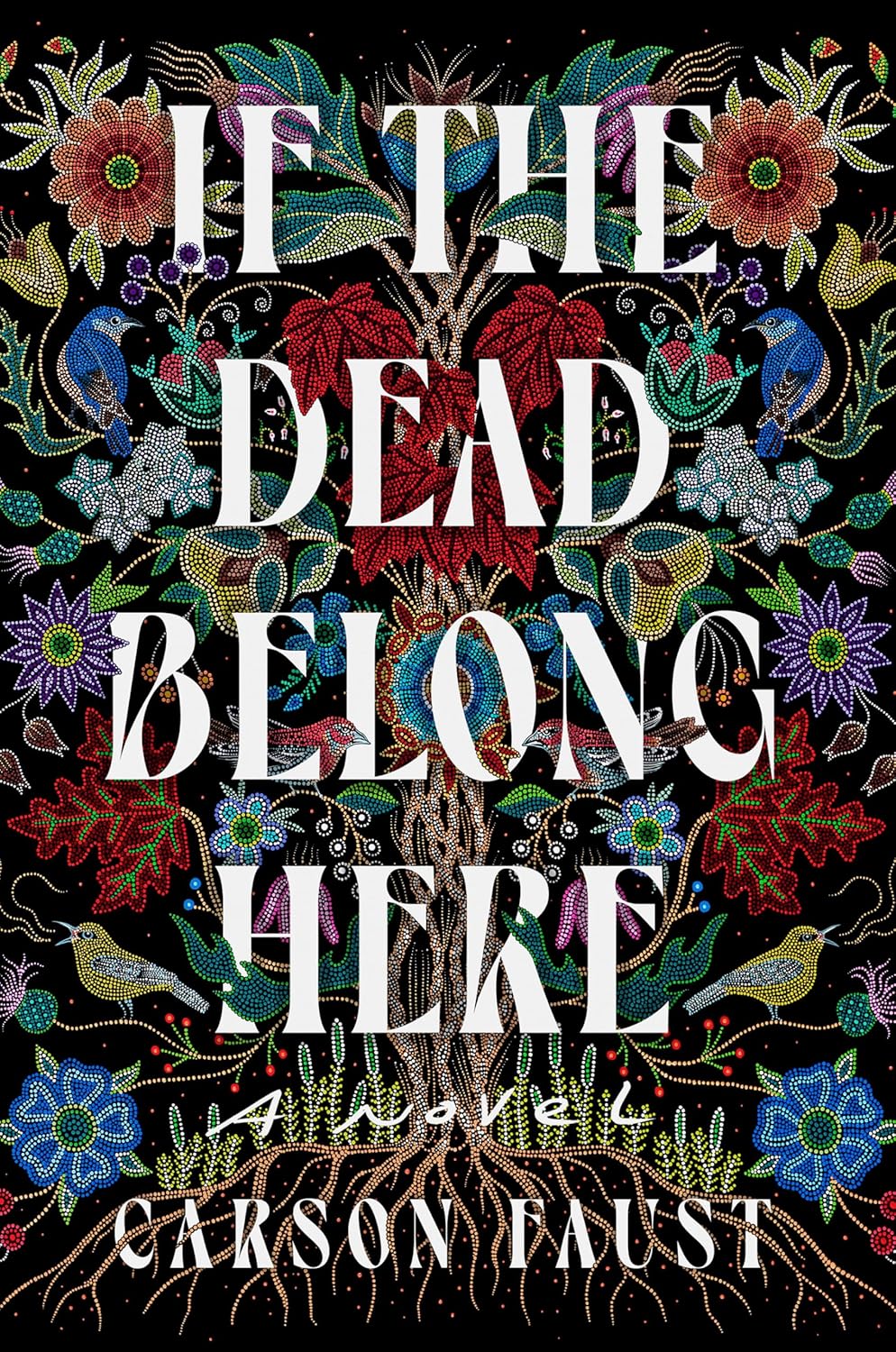

If the Dead Belong Here by Carson Faust

“The intruders enter as quiet as light. They come through the windows, the doors. Slipping in easily, as if their girl left this house open for them. They have been here before …”

In Carson Faust’s If the Dead Belong Here, it is 1996, in the town of Jordan, Wisconsin, and six-year-old Laurel Taylor has vanished in the night. Her mother, Ayita, is lost to the bottle. Her abusive father, Barron, was banished long ago. Her great aunt, Rosebud, from the South Carolina Lowcountry, keeps spinning nonsense tales about the Little People and “the in-between.” It is up to Laurel’s thirteen-year-old sister Nadine to actually do something — but she doesn’t know where to start.

“I’m not sad anymore,” she tells Ayita. “I’m angry. I’m so angry, Mom.”

Her quest will take her several weeks and lead her to places she never thought she’d go – back to South Carolina, back through generations of her family and the many secrets and traumas hidden there, back to stories she can barely find credible, but somehow knows are true.

Are they the key to finding her sister? Or will Nadine, too, vanish into the night?

Filled with ferocity and lyrical brilliance, with ghosts both real and figurative, with the histories and legacies that not only shape our present, but that we build for ourselves, If the Dead Belong Here will linger in your imagination long after the last page … and maybe cause you to leave an extra light on. Just in case.

When Silence Becomes Story

Says the author: “My grandmother’s stories, and, in many ways, the silences I grew up surrounded by, inspired and informed this book. Her eldest son, my uncle Shane, was killed in a tragedy long before I was born. This weighed heavily on my family. His death — and many of the tragedies in my family — were seldom spoken of, so this novel is my way of processing the histories I inherited. By bringing ghosts to the page, I found I was able to process — and try to give life and voice to inherited histories and silences. Writing this work also made me brave enough to ask questions about our family that I didn’t always have the language for. Much of this novel comes from listening.

“In listening to my grandmother’s stories, I found ways of connecting to family histories I once considered lost. My grandma spoke of a healer talking the pain out of her brother’s burns. She told me what liquors mix poorly with our blood and bring out the worst in us. She shared the meanings of certain dreams and told me about conversations she held with ghosts.

The idea of having conversations with ghosts combats the silence I was trying to write my way out of. A ghost is the voice or presence of a person that has been silenced by death, and, often, tragedy.

“Hauntings can seem mysterious or unknowable. But if you’re haunted, there is one thing you know for certain: that you are not alone. Ghosts are just a certain kind of light that we can’t always see. All they want is to be seen. For their stories to be told. For their knowledge to be passed down. Haunting is just a way of staying. And in a book that delves into so much loss, I think a haunting can be a kind of mercy.

“This novel is my attempt to interrogate the silences that have fallen across my family over the years. As I learned about the Natchez folklore surrounding the ucv’ske, or Little People” — Faust is an enrolled member of the Edisto Natchez-Kusso Tribe of South Carolina — “I was struck by their relationship to silence. If you speak of them at the wrong time, there can be harsh, or even deadly, consequences. The ucv’ske can only be seen if they reveal themselves to you. They can make you disappear.

“I found that interrogating my own family’s story came with similar rules: If you hope to find answers, you have to ask the right person at the right time. And even then, the truths might not reveal themselves to you in the end. As with all things, there are consequences for learning. There are also consequences for forgetting. The tension between passing on knowledge and the forgetting of knowledge is very present in the novel. To know is a gift, but it is also a weight. Throughout, these characters learn that isolating themselves in the face of tragedy or difficulty often yields dangerous results. All of these themes coalesce in the novel and are tied to family and folklore alike.”

Shane’s death also inspired the character of Morgan, a gay man who dies in a tragic accident. Faust explores the connections between himself and some of the characters:

“I feel more kinship with Laurel, the sister who disappears, than Nadine. I was a fairly withdrawn child as I was growing up. Much of my time was spent drawing alone or dreaming up imaginary worlds to inhabit. Laurel’s curiosity about the ucv’ske also mirrors my interest in better understanding my tribe’s history and culture. Despite being young, Laurel tries to bring her family into these worlds — and increase their understanding — before she is swept away.

Living Between Worlds

“With Morgan, there is a different kind of kinship. Morgan is queer, like myself, even if he doesn’t have the language to express that, necessarily. In many ways, I allowed Morgan more bravery than I had at his age. Morgan more fully embodies his queerness — and is unafraid of the consequences of being his truest self. I think, given the era he lived in, that bravery becomes part of the tragedy that falls upon him. But I wanted to make sure to allow him moments of joy and clarity.

“Laurel and Morgan both share this tension of walking in two worlds. In both of these worlds, they have to negotiate which aspects of themselves they can embody. As a queer person, as a two-spirit person, and as a Native person moving through the world, I think that tension often appears in my writing.”

And the tension won’t let up in the next book:

“The characters who have been visiting me for the next work have been taking shape for a while now. Like a lot of debut novels, I think of If the Dead Belong Here as an origin story. It stretches across time, geography, bloodline, and came to me with a chorus of voices.

“There is really just one visitor with me for this next project, as of right now. The characters in my debut were displaced from their ancestral lands by tragedy. The visitor for this next project feels much more tied to our ancestral land — they have only ever known the humid air and cypress trees.

“If my debut novel centers around looking backward and honoring my family’s past, this new novel feels more like looking forward. There are still hauntings, of course. This project came to me as my grandma told me about night hags — shadowy figures that hover over their victims at night and strangle the life out of them. My grandma has been plagued by them for most of her life and I know many family members who these figures have been passed to. The idea of there being presences who visit us who are not our relatives — that are more purposefully malevolent …”

I can feel the shivers already. Maybe you should leave that extra light on.

About Carson Faust:

Carson Faust is the debut author of If the Dead Belong Here (Viking, 2025). He is two-spirit, and an enrolled member of the Edisto Natchez-Kusso Tribe of South Carolina. He is the recipient of artist fellowships and residencies from the McKnight Foundation, the Jerome Foundation, and the Camargo Foundation. His fiction has appeared in TriQuarterly, ANMLY, Waxwing Magazine, among other journals, and has been anthologized in Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology (Vintage, 2023). He lives in Minnesota, where he is at work on a second novel.

Carson Faust is the debut author of If the Dead Belong Here (Viking, 2025). He is two-spirit, and an enrolled member of the Edisto Natchez-Kusso Tribe of South Carolina. He is the recipient of artist fellowships and residencies from the McKnight Foundation, the Jerome Foundation, and the Camargo Foundation. His fiction has appeared in TriQuarterly, ANMLY, Waxwing Magazine, among other journals, and has been anthologized in Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology (Vintage, 2023). He lives in Minnesota, where he is at work on a second novel.

He is represented by Annie Hwang of Ayesha Pande Literary.