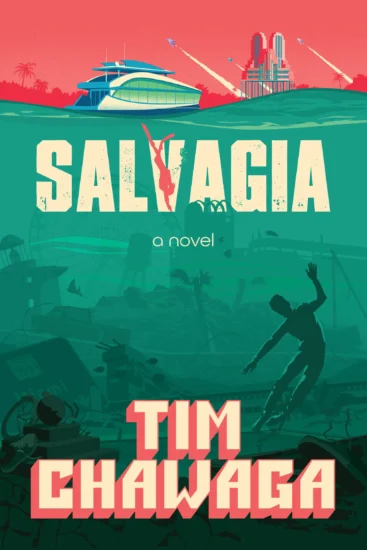

SALVAGIA, my debut sci-fi mystery, is set along the future flooded Florida coast. Mean season is twice as long and twice as strong, and Miami is long abandoned. Despite this, lots of money is about to come in to build it all up again and make most of the same mistakes that ruined it in the first place. They’ll build fast and cheap and dirty, on ground that is less than solid, against all regulations and common sense. Everything, I’m sure, will be fine.

SALVAGIA, my debut sci-fi mystery, is set along the future flooded Florida coast. Mean season is twice as long and twice as strong, and Miami is long abandoned. Despite this, lots of money is about to come in to build it all up again and make most of the same mistakes that ruined it in the first place. They’ll build fast and cheap and dirty, on ground that is less than solid, against all regulations and common sense. Everything, I’m sure, will be fine.

The climate warms, the seas rise, humans take to the stars; no matter the frontier, whether it be new or just newly eroded, there will always be a group of people using their vast wealth to ignore both regulations and common sense to build something inadvisable, and often tacky. The following is an incomplete list of such follies in fiction, human vs. environment: Ahab’s obsession with mastering nature followed swiftly by Ahab’s tendency to get owned by whales.

Jurassic Park might spring to mind, but I’ve excluded it here — Isla Nublar itself is a natural paradise, and it’s not its fault that it is now infested with dinosaurs. The Lost World’s Isla Sorna hits closer to the mark and might deserve an honorable mention since I don’t think it’s advisable to abandon your dinosaur factory in the middle of Hurricane Alley, but I can’t remember if that was a movie element or a book element. The Crichton estate doesn’t need our money anyway.

In the real world, aside from the occasional combustion of a deep-sea sub’s worth of millionaires, rarely do unqualified people using money to put up a lightning rod against their own mortality do so without fallout when the lightning inevitably strikes. Just like in life, the victims of the below examples are often not the wealthy, or just the wealthy, but the ones who trust them, who buy what they are selling. Some of them, the smart and lucky ones, find ways to avoid the storm.

Others are the storm themselves.

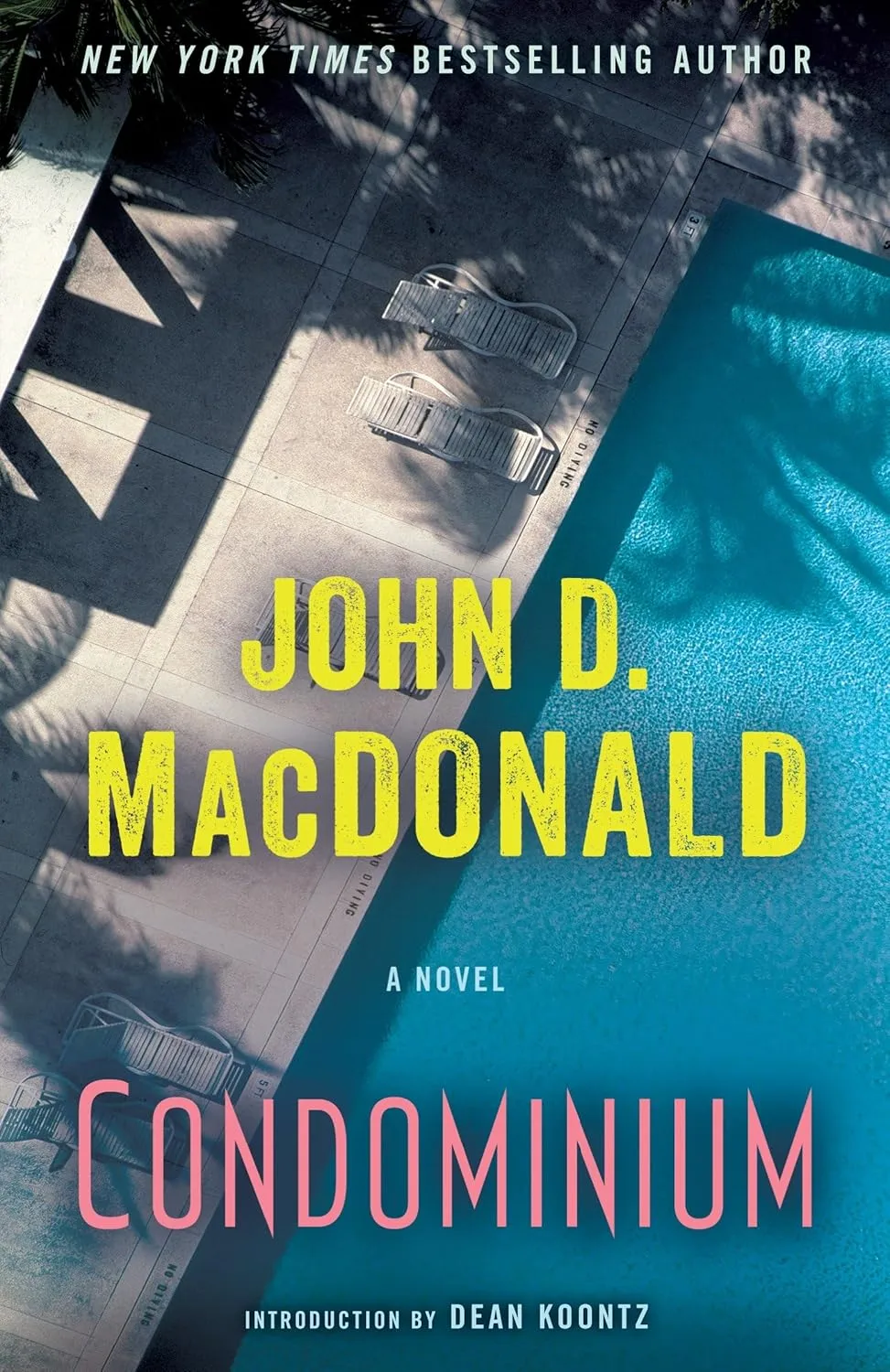

Condominium by John D. MacDonald

SALVAGIA is inspired by the work of John D. MacDonald, who often writes about the 20th-century development boom in Florida, most notably through his Travis McGee series. MacDonald is a master of sketching a full character in two sentences or less, and he uses that skill in this standalone to efficiently draw a three-dimensional cast of over a hundred people: the entire population of Golden Sands, a hastily built, corner-cutting high-rise on an offshore key on the Gulf side of Florida.

Chapter by chapter, MacDonald shows that Golden Sands is a shaky house of cards, not just the building itself (although very much also the building itself), but the discontented and unreliable people who built and live in it, including the builders, bankers and county commissioners. Their small, seemingly inconsequential selfish choices add up to something whose very foundation is cracking.

Then, before you know it, it’s hurricane season, and somewhere in the Gulf, the clouds are gathering.

The Terraformers by Annalee Newitz

Annalee Newitz’s book about a far-future terraforming corporation turning a dead planet into a flippable habitat is conceptually dazzling, full of good speculative environmental problem-solving, and fascinating questions on sentience and freedom. The villain is an interstellar corporate executive who is sometimes played for laughs but can be ruthlessly Old Testament, threatening the entire planet and even her employees with annihilation. To beat her, those who see the planet as something more than a product will have to find a surprising way to fight back.

New York: 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson

What’s the point of saving New York? The entire city, but particularly Lower Manhattan, the low-level, sea-ringed site of the most valuable real estate in the world, will probably be a bellwether for what is possible when it comes to retrofitting our existing habitats to climate change. Most of the rich people in Robinson’s future New York, which has suffered 50 feet of sea level rise, have actually moved uptown, to super skyscrapers built on the towering bedrock cliffs of Morningside Heights. The downtown habitable city is a Venice-like series of canals and skyways, and many of the characters live in a co-op in MetLife Tower on 23rd Street, whose ground floor is entirely underwater. It’s still New York, which means affordable housing is already in short supply. And the waters are still rising.

Fever Beach by Carl Hiaasen

Unlike Condominium, the only thing really inadvisable about development building in Carl Hiaasen’s Florida isn’t storms or weather, it’s just a guy with anger issues and unlimited money stopping by to blow it up. That’s protagonist Twilly Spree, who is on a mission to use his wealthy grandfather’s trust fund money to derail a corrupt and ugly development deal and ruin the lives of the people behind it. But he’s still just one person. Fortunately, the wealthy are inherently incompetent here, unbelievably, hilariously stupid. They start low and only go lower, and do much of Twilly’s work for him.

Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers

Panga is a far-future society living sustainably with nature, in limited areas, with most of the planet rewilded. No rich people in sight. Coincidence? This is the exception that proves the rule of this list. The lack of capitalism creates the necessary space for a beautifully written, thoughtful rumination on seeking purpose and meaning out of life beyond needs, whether human or robot.

Blackfish City by Sam J. Miller

Qaanaaq is a city built on top of an old oil rig in the Arctic Circle. It’s positioned over a geothermal heat vent and one of the last safe havens after the devastating climate wars. It is a city whose people are largely refugees, under the thumb of an oppressive ruling class.

And then, one morning, a spear-carrying woman arrives on the back of an orca, accompanied by a polar bear. Oppression of the working class often goes hand in hand with oppression of the natural world, and the opening image of this book says it all: nature is coming, and she is very pissed.

Escape Velocity by Victor Manibo

A prep school reunion that takes place at the Altaire, a luxurious space station, with alums that are all members of the elite. The reunion doubles as spaceflight hours, to make it easier for them to earn slots for the new Mars colonies. The book opens with one of these alums, Henry, waking up outside the station, floating in space with no jetpack fuel and limited oxygen. Things get worse from there.

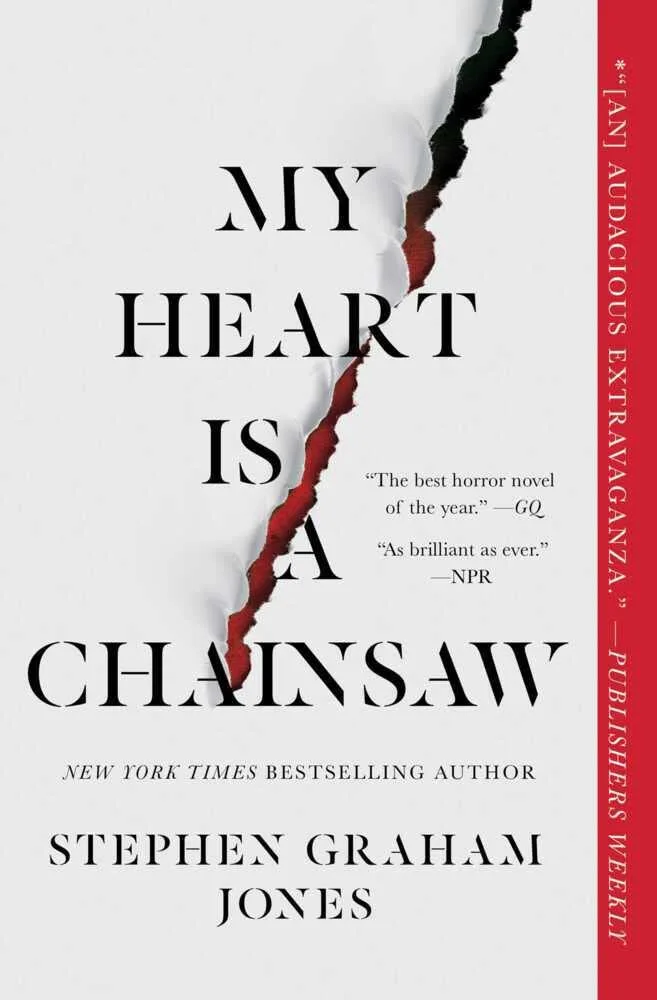

My Heart is a Chainsaw by Stephen Graham Jones

The only horror book on this list, and the first of a trilogy in which bad things definitely happen to rich people, but also to pretty much everyone else. Jade Daniels is a horror movie expert/freak who desperately wants a slasher to come to her little town of Proofrock, Idaho. When a group of wealthy businesspeople arrive and start building mansions on top of a summer camp with a bloody past, her wish comes very true. Jones’ prose is the best and bloodiest there is.