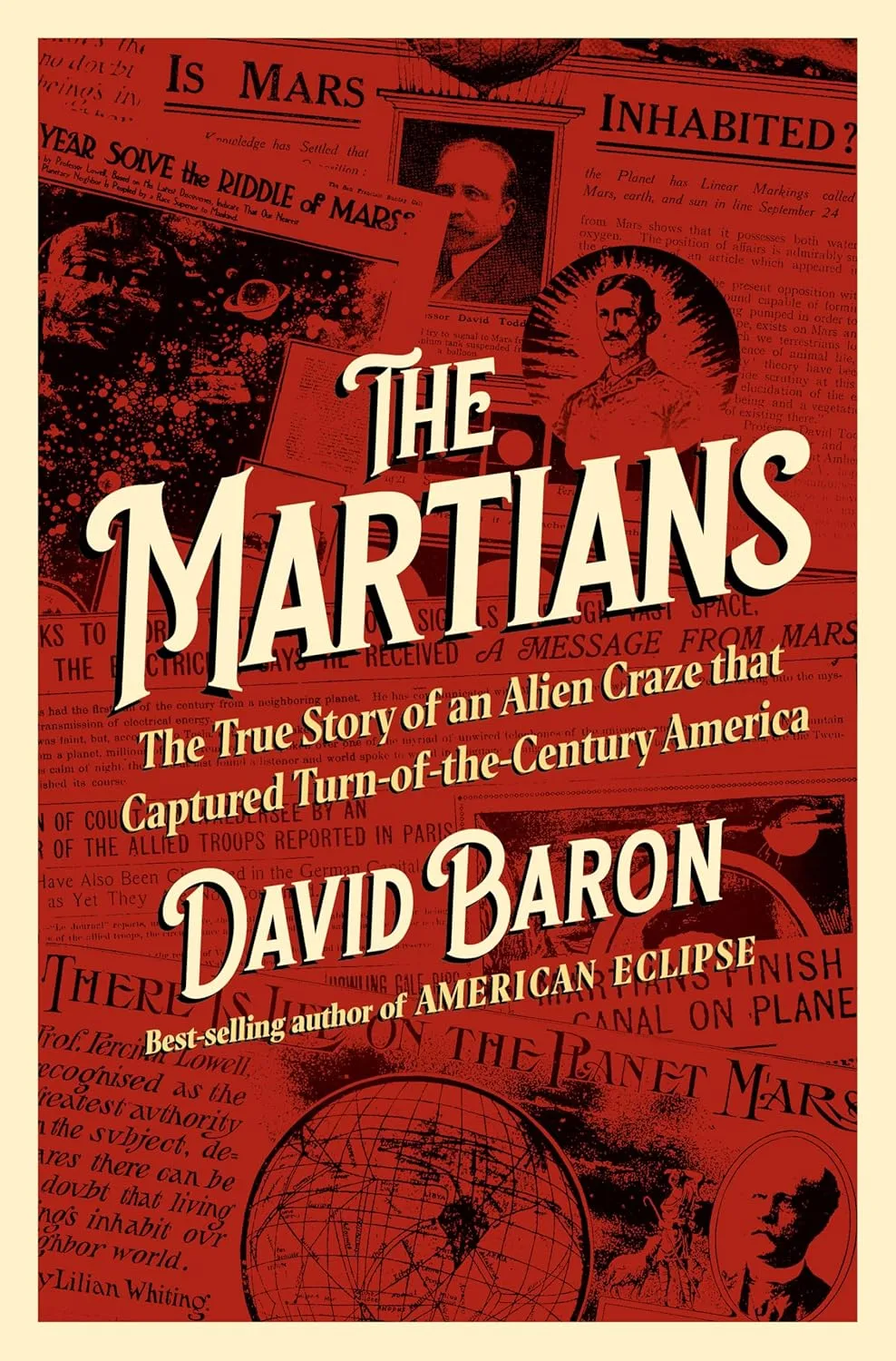

The Martians by David Baron

Of all the planets in our solar system, Mars has long possessed a special allure. Indeed, its reddish hue caught the eye of many an ancient human who stared into the night sky. Starting with Galileo’s telescope in 1610, technology brought the planet into better focus. Until the late nineteenth century, Mars largely drew the interest of astronomers who developed theories about habitation, rotation, and climate.

Then, unexpectedly, Mars became embedded in popular culture — a far-flung object that seized the imagination of all ages.

In The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America, journalist David Bacon gives us a blow-by-blow history of Americans’ obsession with Mars and Martians. The author “arrived on Earth in the 1960s,” he reveals playfully, and was “raised on spacemen and Martians.”

Therefore, he is well-qualified to describe the obsession that straddled the 19th and 20th centuries: several decades when Earth had a “sister planet,” intelligent beings watched us from outer space, and Martians with antennae, tentacles and big eyes might decide to attack or simply wander among us undetected. How sensational was that!?

Alien Life and Canals

The idea of life on Mars was not universally accepted, but its challengers tended to be quiet academics. In contrast, the fervor about Martians was driven by prominent men and women, including author H. G. Wells, banker J.P. Morgan, inventor Alexander Graham Bell, engineer Nikola Tesla, and a feminist writer-lecturer, Mabel Loomis Todd, wife of Amherst College astronomer David Todd.

Most persistent of them all, Percival Lowell, scion of a wealthy Boston clan, graduated from Harvard in 1876 and delivered a commencement address about the solar system. The speech stirred popular interest in Mars. Subsequently, Lowell created a scandal when he broke off a high society engagement to a local belle and sailed to Asia in 1883. Within four months, he made a triumphant comeback, leading a “Corean” delegation to meet President Arthur at a New York hotel.

Lowell created a new persona for himself. He was a world traveler and astronomer who drew crowds to his lectures about “an advanced civilization living next door.”

Neither a scientist nor a professor, Percival Lowell was, in fact, a bit of a quack. Yet he captured the public’s imagination and influenced the study of Mars at a time when the U.S. already possessed a scientific establishment. The University of Virginia had founded the nation’s first astronomy department in 1825. Through the 19th century, many colleges and universities followed suit, including Vassar, where Maria Mitchell became America’s first female astronomer. Williams College (1838) and the University of Michigan (1854) were among the first schools to build observatories.

In 1894, Lowell built his own observatory, Mars Hill, in Flagstaff, AZ. There, with his telescope aimed at the red planet, he discerned a grid of canals and double canals which the Martians had dug, he claimed. He continued to spew unproven theories about alien life and the canals. This had the effect of hampering research until 1909, when the Yerkes Observatory opened in Wisconsin and astronomer Edward E. Barnard captured the clearest images yet of Mars — without a canal in sight.

Until his death in 1916, Lowell remained a “canalist.” He never stopped looking for evidence to support his “hardened theory,” writes Bacon.

Why the Frenzy?

The Mars craze came along at a time of profound social change worldwide. In the U.S., industrialization had widened the disparity between the working class and “malefactors of great wealth,” as Theodore Roosevelt characterized the Gilded Age robber barons. Urban populations skyrocketed while millions of immigrants arrived at American shores. New inventions included the telephone, typewriter, automobile, light bulb, radio transmission and X-ray; scientists discovered vaccines for diphtheria, tetanus and rabies.

While many developments were positive, Bacon suggests that the nation felt vulnerable. President Garfield’s assassination in 1881 sparked a series of attacks on Western heads of state. In 1898, the U.S. entered the Spanish-American War, its first war since the Civil War. There were financial panics in 1893 and 1907. Labor unrest led to violence. Many feared women’s suffrage.

As Americans worried about the future of civilization, they became more accepting of crazy ideas like an idyllic life on Mars.

The rise in literacy also contributed to the alien craze. As newspapers and dime novels proliferated, more Americans than ever could read about Martians. These folks didn’t want scientific proof; just a great story.

In The Martians, David Bacon has given us another one.

About David Baron:

David Baron is an award-winning journalist and author who writes about science, nature and the American West. Formerly a science correspondent for NPR and science editor for the public radio program The World, he has also written for The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, Scientific American and other publications. While conducting research for his latest book, The Martians, he served as the Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress Chair in Astrobiology, Exploration and Scientific Innovation. David is an avid eclipse chaser, and his TED Talk on the subject has been viewed more than 2 million times. An affiliate of the University of Colorado’s Center for Environmental Journalism, he lives in Boulder.

David Baron is an award-winning journalist and author who writes about science, nature and the American West. Formerly a science correspondent for NPR and science editor for the public radio program The World, he has also written for The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, Scientific American and other publications. While conducting research for his latest book, The Martians, he served as the Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress Chair in Astrobiology, Exploration and Scientific Innovation. David is an avid eclipse chaser, and his TED Talk on the subject has been viewed more than 2 million times. An affiliate of the University of Colorado’s Center for Environmental Journalism, he lives in Boulder.