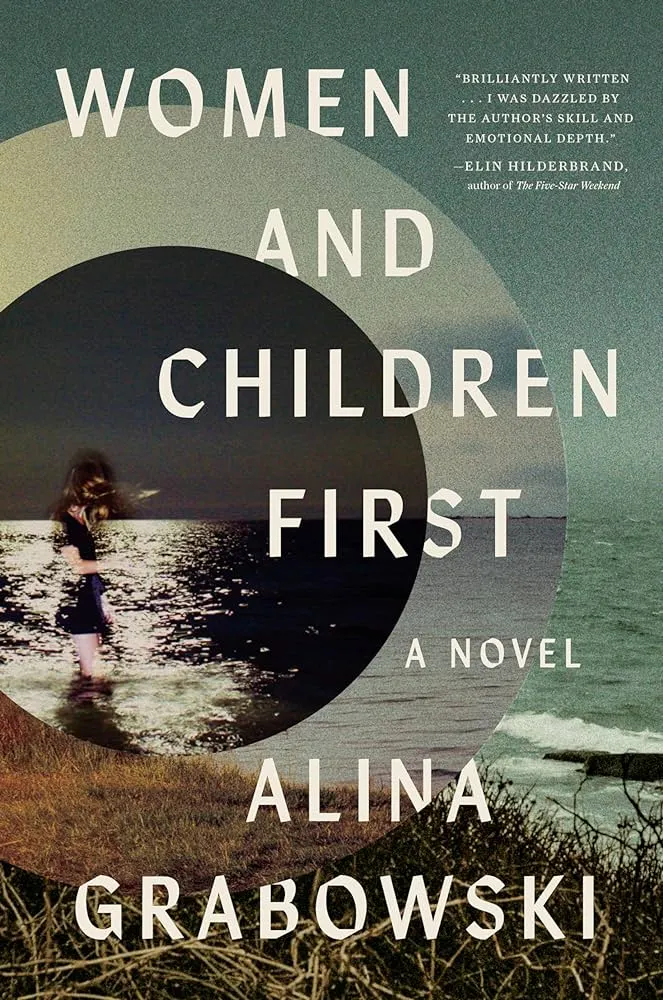

Women and Children First by Alina Grabowski

A wonderful debut by Alina Grabowski, Women and Children First follows the lives of ten women before and after the death of a high school student in a coastal Massachusetts town. It is a story about community and how people’s lives are intertwined, female friendships, agency and memory. Grabowski shows us the importance of setting and the power of nature as she writes this voice-driven mystery in first person.

I enjoyed getting to know all of the women, and with every viewpoint revealed by a different female character in each chapter, I was gathering more information about what may be the truth about the tragedy, the relationships between all the small-town residents and how personal truths and points of view can greatly vary.

It was a treat to spend time with Alina to learn more about her writing process and the different characters that appear in Women and Children First. You can view our Book Nation interview below.

Q & A with Alina Grabowski:

Q: How long did it take to write Women and Children First and where did you come up with the premise?

A: I worked on WACF for close to eight years! I wrote a very different version of Jane’s chapter when I was in undergrad, and it was one of the first pieces I wrote that felt true to what I wanted to be doing, and exploring, as a writer. Questions of agency, motherhood, place and violence were all contained in Jane’s narrative. Then I kept coming back to Nashquitten in various stories I was working on in graduate school, and by the time I’d assembled my thesis I had this constellation of Nashquitten stories.

Q: This story’s narrative is brilliantly woven together in a way that seems like it must have been a complex approach. Why did you decide to tell the story from 10 different viewpoints? How did you organize your thoughts about each?

A: I’m very interested in what I’ve been calling kaleidoscopic narratives—stories that aim to examine narrative elements through multiple perspectives or angles. I’m fascinated by the fact that we’re all experiencing the shared world through our own particular lens, and I wanted to capture that in the novel. I was also interested in creating a portrait of a community and place, as opposed to following one character’s development. I can’t say that I actively organized my thoughts—it was more that the life of each woman grabbed me in some way. I’m a very voice-driven writer, and I wanted to follow these ten different voices. I think some authors find a particular image arresting, or have a plot in mind, but my way into a story has always been through hearing a character’s voice and wanting to know more.

Q: When planning out the story, did you fully develop the character of Lucy, how she was connected to each person, and how she died in more detail, to help with organization?

A: Lucy is very much an active absence in the book, and that was one thing I knew I wanted from the start. Some readers have asked me if I ever considered including her voice, and the honest answer is no. I wanted the reader to build an idea of Lucy through the women’s impressions of her — part of the tragedy of the book is that Lucy never gets to say what happens to her. She doesn’t get to speak. And I think that’s an honest element of tragedies like these; you very rarely get a definitive answer of what occured. And people construct their “truth” based on what they’ve heard, which is of course subjective, to a degree. In terms of organization, I did have a big circle on the white board in my office with all the character names written around it, like the numbers on a clock. And I drew lines to connect characters who overlapped, to make sure no one was overly isolated or overly involved.

Q: How did you decide to set the story in a fictitious, coastal MA town?

A: Nashquitten is based on the town where I grew up, on the south shore of Massachusetts. For me, the real joy of writing is inventing characters — I rarely take inspiration for a character from a real person, though I might incorporate a detail or gesture I’ve observed. I love writing about setting, but I can’t create it from scratch like I can characters. Some writers are so talented at creating worlds and places from their imagination, but I need a reference, something I’m looking back on and trying to recreate. And I haven’t lived in my hometown for over a decade now, so it was also pleasurable, remembering what the place that had shaped me was like. The small town dynamics are also so essential to the story, as well as the ocean and religion. I felt like I intimately knew those aspects, and that they could be used in the story in an interesting way.

Q: Who was the easiest narrator to write? The most difficult? Your favorite?

A: I don’t think any one narrator was the easiest or most difficult, per se. Since all the narration is first-person, the challenge was to occupy the mindset of each character. I wasn’t just describing how someone was acting or what they were saying, but really trying to replicate their thinking. What can be difficult is that you have no distance from the characters in this approach; in third-person, if a character is being reserved or withholding, the narrator can analyze why. But for some of these characters I had to be patient and hope they would open up to me as I continued to write. I’m very fond of them for that reason — I feel like I know all of them so intimately after writing their chapters. But Mona was particularly fun, because she’s somewhat unhinged and very different from myself. I was just waiting to see what she’d say next.

Q: How did you decide on each of their names?

A: This was very intuitive! I wish I had a better answer than Mona felt like a Mona and Jane felt like a Jane, but that was truly it!

Q: Marina tells a story of two girls who are left alone at the lighthouse and deter a warship. Can you tell us more about that story and its significance?

A: I mention this in the author’s note, but this story is based on the real story of Rebecca and Abigail Bates, who were nicknamed the American Army of Two. The event took place in my hometown and I remember being told the story many times as a child. I think of WACF as very much about narrative; the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and what we’re capable of, and also how stories defy ownership, as they morph through being retold and passed down. Additionally, I’m interested in the shakiness of truth, and how we all build our own understanding of truth. I incorporated the Bates story as a nod to both of these themes.

Q: You have several characters who don’t have chapters that reveal their voice, Lucy, Eric (her cousin), Rob/Cole, Brynn’s sister to name a few … Did they ever have their own chapters? Did you have a set formula or a list of attributes or inclusions each chapter required?

A: As I was mentioning before, it felt very important that Lucy didn’t have a chapter. That would have undone the project of the book, which is to explore how we all have such individual understandings of the people that move through our lives, and how unknowable we are to even those who think they know us most intimately. And I knew that none of the male characters would have their own chapter. I wanted to exclusively explore the perspectives of women and how the challenges they face in this town. I didn’t have a formula as to who would warrant their own narrative — it really was about following voices I found intriguing. I think the largest female character who doesn’t get a chapter is Janet Cushing, the school principal and Olivia’s mother, and that’s because she’s an authority figure and has decision-making power. So often how choices are made at institutions like schools is opaque to those most affected by such decisions, and I wanted to replicate that.

Q: What is the significance of the title?

A: The tile is a reference to maritime law, which is probably how most people are familiar with it. It’s ironic in that sense — there’s the idea that men stay back to allow women and children to embark to safety, but in WACF it’s so often the men that are in fact endangering the women and children of the book. I also liked the fact that it gestures toward the sea, which is a large part of the landscape in Nashquitten.

Q: Can you tell us what Lucy’s secret photography project was?

A: Ha! I will say that it’s about agency and representation, but leave it at that. I love the idea that different readers have different ideas about what it was.

Q: Your book would lend itself nicely to a 10-part limited series like Broadchurch — any talk of it getting to screen?

A: Unfortunately, I can’t talk about this. All I’ll say is that I’m keeping my fingers crossed!

Q: How were you notified that SJP wanted to publish your book at Zando?

A: This was a very funny moment that I remember quite clearly. My agent had submitted the book on Monday, and I expected that I wouldn’t hear anything for a while. We’d actually submitted to Zando because I really admired an editor there, Emily Bell, who ended up becoming my editor (she’s edited Catherine Lacey, Laura van den Berg, and Lindsay Hunter, among others). Then my agent called on Friday, and said, “Guess who loves your book?” And I of course was thinking — hoping! — it was one of the editors we’d submitted to. And when I asked who, she said, “Sarah Jessica Parker!” And we both just laughed in disbelief. We had no idea when we sent the book that it’d be shared with SJ. That was a really wild, incredibly lovely surprise.

Q: What have you read lately that you enjoyed and recommend?

A: I’ve been having a summer of big books! I really loved The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen and Skippy Dies by Paul Murray, both novels that aren’t normally what I read but that I adored. Before that I was rereading some beloved books that I incorporated into summer teaching and lectures—Jazz by Toni Morrison, Edinburgh by Alexander Chee, Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout and Drinking Coffee Elsewhere by ZZ Packer.

Q: What is up next for you?

A: I’m working on book two! I don’t want to say too much, but it’s quite different from WACF — though still using New England as muse.

Q: Where can we follow you?

A: You can sign up for my newsletter on my website, www.alinagrabowski.com, or follow me on Instagram @alinagrabowski_.

This story appears through BookTrib’s partnership with BookNationByJen. It first appeared here.

Check out other posts from BookNationByJen

About Alina Grabowski:

Alina Grabowski grew up in coastal Massachusetts and holds degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and Vanderbilt University. Her writing has appeared in Story, The Masters Review, Joyland, The Adroit Journal, and Day One. She has received scholarships from Aspen Summer Words, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, and the Juniper Summer Writing Institute. Her debut novel, Women and Children First, was published by SJP Lit in 2024. She lives in Austin, Texas.

Alina Grabowski grew up in coastal Massachusetts and holds degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and Vanderbilt University. Her writing has appeared in Story, The Masters Review, Joyland, The Adroit Journal, and Day One. She has received scholarships from Aspen Summer Words, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, and the Juniper Summer Writing Institute. Her debut novel, Women and Children First, was published by SJP Lit in 2024. She lives in Austin, Texas.