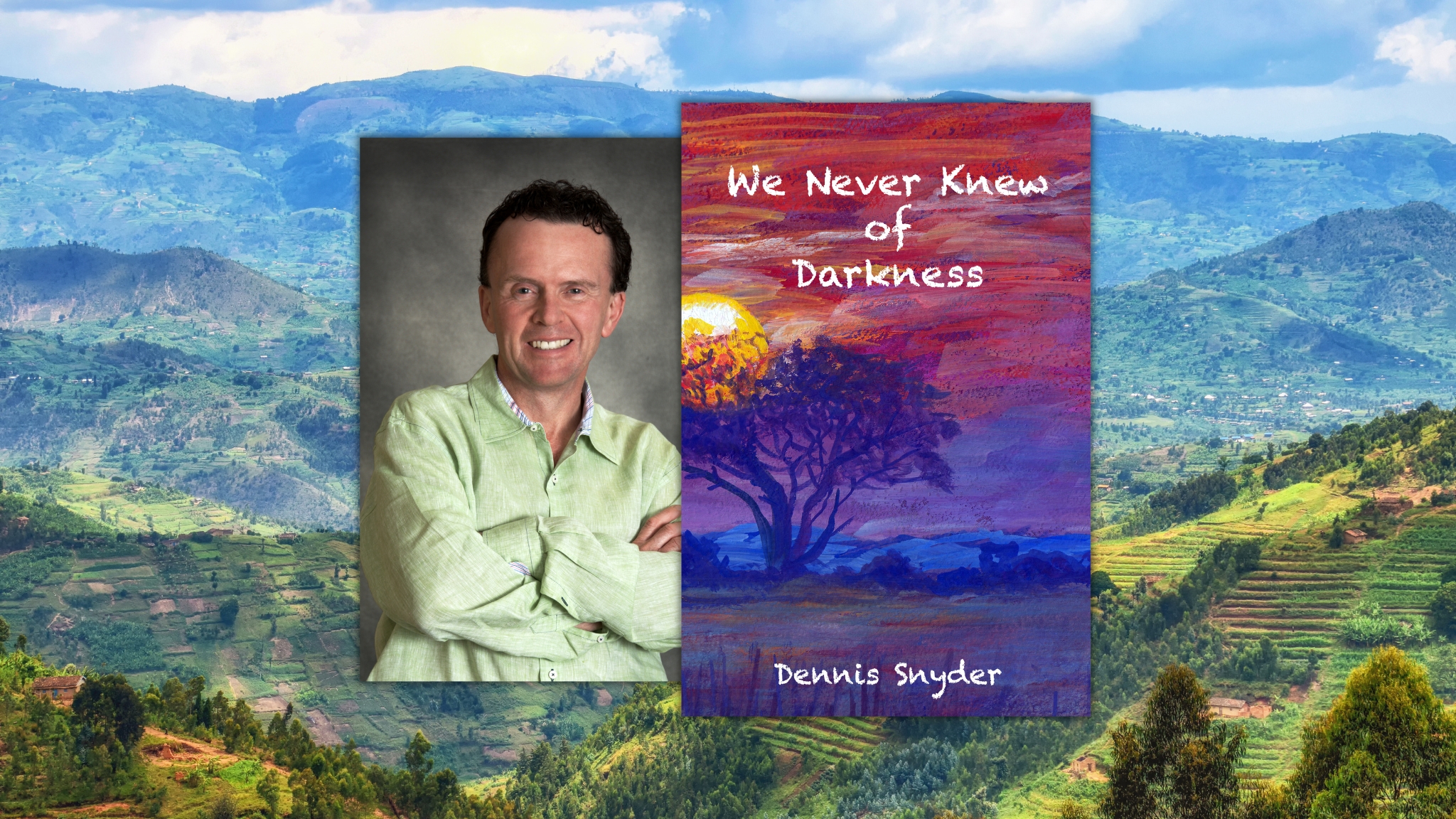

Dr. Dennis Snyder’s novel We Never Knew of Darkness begins with the smell of sweat and stale blood during the gut-wrenching and unconscionable violence of the Rwandan genocide.

In April 1994, Hutu extremists assassinated Rwanda’s president and then embarked on a campaign of ruthless genocide against the minority Tutsi population. Elijah Mutabazi, a sergeant in the Rwandan army, finds his younger sister slaughtered and his father grievously wounded.

We Never Knew of Darkness follows Elijah’s dramatic journey as he transforms from a valiant defender of his village to a drug-addicted soldier and prisoner, then a man bent on bitter revenge, and finally to a doctor dedicated to healing all people, even his former enemies. The book is fiction, but the unspeakable horror of those months is not, and the characters in the book are based on real people, heroes and villains alike.

We talked with author Dennis Snyder about the inspiration behind this book and about his harrowing time in Rwanda.

Q: Why did you write this book?

A: In 2005, I had the privilege of leading the first volunteer medical mission to Rwanda after the 1994 genocide. Since that time, I have traveled back to Rwanda with our surgical team about a dozen times, keeping a personal journal on each trip. In so doing, I had the ever-increasing urge to tell of my — of OUR — experience in this beautiful and impossibly resilient country. I wanted to make every effort to tell that story, centering the narrative on the unimaginable horror that occurred in Rwanda only a few years earlier.

Q: You have written a novel, but you were there to experience the horrors in real life. How difficult was you to put together this story?

A: I “felt it” throughout the entire writing/editing process, no question there. Neither I nor any of the other volunteers were in Rwanda during the months (Spring 1994) of the genocide, and never at any time during our first visit or subsequent visits did we witness any evidence of active/residual violence. But the scars left behind by such an inconceivable level of hatred and mass killings were everywhere — abandoned homes and villages; memorials along every road and footpath; survivors without limbs or bearing evidence of other horrific injuries; a palpable suspicion of who we were and what we were doing. Perhaps worst of all were the countless citizens who had gone without medical care for years, or perhaps had never once seen a doctor. Although writing this story was reliving all of this, I constantly reminded myself that the challenge I had in front of me was nothing — absolutely nothing — compared to what those I saw and the treated had lived through. The strength and perseverance of the Rwandan people have no equal.

Q: Although it’s clear that time spent in Rwanda will affect anyone who’s been there, what experience or discovery affected you the most?

A: Although I already had a 20+ year career in medicine by the time I first traveled to Rwanda, witnessing the manifestations of psychotic episodes in the survivors of that country’s genocide was in every way profound. The visceral screams emanating from these victims were horrific — as if some inner poison was begging for release. I attempted to relate one such experience in chapter 24 of We Never Knew of Darkness, and I can state unequivocally that there is no medical term, or piece of diagnostic jargon, that adequately delineates the ravages of these patients’ plight. Truly frightening.

Q: Can you explain the difference between Hutus and Tutsis? What was the motivation of the Belgian government to issue ID cards? How did they determine who was what?

A: In truth, there is no difference whatsoever between a Hutu citizen and a Tutsi citizen. None. Pretend for a minute that you and your best friend both have a solid job, a fine home, and a good income. Through untold centuries of Rwandan history, you would both be considered Tutsis. Now, say you lose your job, your home, and by necessity you enroll for public assistance. You are now a Hutu, while the friend you love remains a Tutsi. But a few years later, when you are again employed, living in a new home and heading up the corporate ladder, you are considered a Tutsi. But your bestie, who is now unemployed and living with a relative, is a Hutu.

The designation of Hutu and Tutsi was based solely on one’s present socioeconomic footing, equivalent to what one might consider middle/upper middle class (Tutsi) and lower middle class/unemployed (Hutu). The Belgian government, however, having already anointed itself ruler of the Rwandan people and sole owner of the nation’s resources, sought to further control the citizenry by designating taller people with refined features as Tutsis, and those of shorter stature with darker skin and rugged features as Hutus. By extension, the Belgian intelligentsia considered Tutsis to be more intelligent, and thereby more capable in lording over the masses… those masses being the “less-educated, crude, illiterate” Hutus. The Belgians invented a malignant, vile dichotomy by way of nothing more than pseudoscience, creating an apartheid system that had no basis whatsoever in the millennia of Rwanda’s history. Within a generation, this factitious division became one that every Rwandan believed in, as each and every citizen was compelled to carry an ethnic identification card that was as immutable as it was fabricated. This would lead to the slaughter of a million innocent children, women and men.

Q: Are there flare-ups of conflicts between the two groups today? How do the Twa usually identify themselves, and do they lean toward either Hutu or Tutsi?

A: Today, by decree of the Rwandan government, there is no distinction between Rwandan citizens, and ethnic ID cards are illegal. Conflicts along Rwanda’s border with the Democratic Republic of Congo occurred in the years immediately following the genocide, but such tensions have largely abated. The threat, however, will never completely disappear. Twa citizens comprise less than 1% of the Rwandan population, and their tribes generally live in more remote regions. Through the years of colonial rule, they did not align with either Tutsis or Hutus. Twa citizens are readily recognizable by their very small stature.

Q: When did you first become inspired to specialize in cleft surgery, and to treat patients with other birth defects and facial and neck tumors? During your time in Rwanda, what were mealtimes like, sharing dinnertime with those you worked with?

A: Participating in the care of sick children — in particular children born with horrible deformities or having other severe maladies — is an honor and privilege beyond any other. And to care for children who were born in and live in a part of the world where there is essentially no access to medical care is an experience beyond words. The surgical procedures themselves present a never-ending challenge, and believe me, you never stop learning. Never. Should you ever meet a surgeon who has learned it all, my advice is to run away.

Mealtimes in Rwanda were a joy, each and every time. The food was from the farm we were living on, and the only thing better than the fresh vegetables, fruit and grain was the time we spent with our Rwandan hosts. I did my best to tell of this experience in chapter 32, but I only scratched the surface.

Every day in Rwanda was for me a singular experience, a forever memory. I hope you enjoy the read as much as I did putting it on paper.

About Dr. Dennis Snyder:

About Dr. Dennis Snyder:

Dr. Dennis Snyder is one of the founders of Medical Missions for Children (www.mmfc.org), a volunteer organization that provides free surgical care to children with severe congenital deformities, neck and facial tumors, and burn injuries. Dr. Snyder led the first medical team to visit Rwanda following the 1994 genocide, setting up an operating room and initiating a pro bono surgical program at a small hospital in the town of Gitwe. Since that time, MMFC has completed twenty-five missions at multiple sites in Rwanda. One hundred percent of the royalties from We Never Knew of Darkness will be donated to Medical Missions for Children, which carries out over twenty volunteer missions per year in eleven different countries.