“La vie de Boheme” was not an American phenomenon. It emerged in the Latin Quarter of Paris during the early 19th century and arrived flamboyantly in New York, Boston, and San Francisco around the time of the Civil War. Bohemians dressed rakishly, lived unconventionally, boasted pro-labor, sometimes socialist sympathies, and devoted themselves to creative expression.

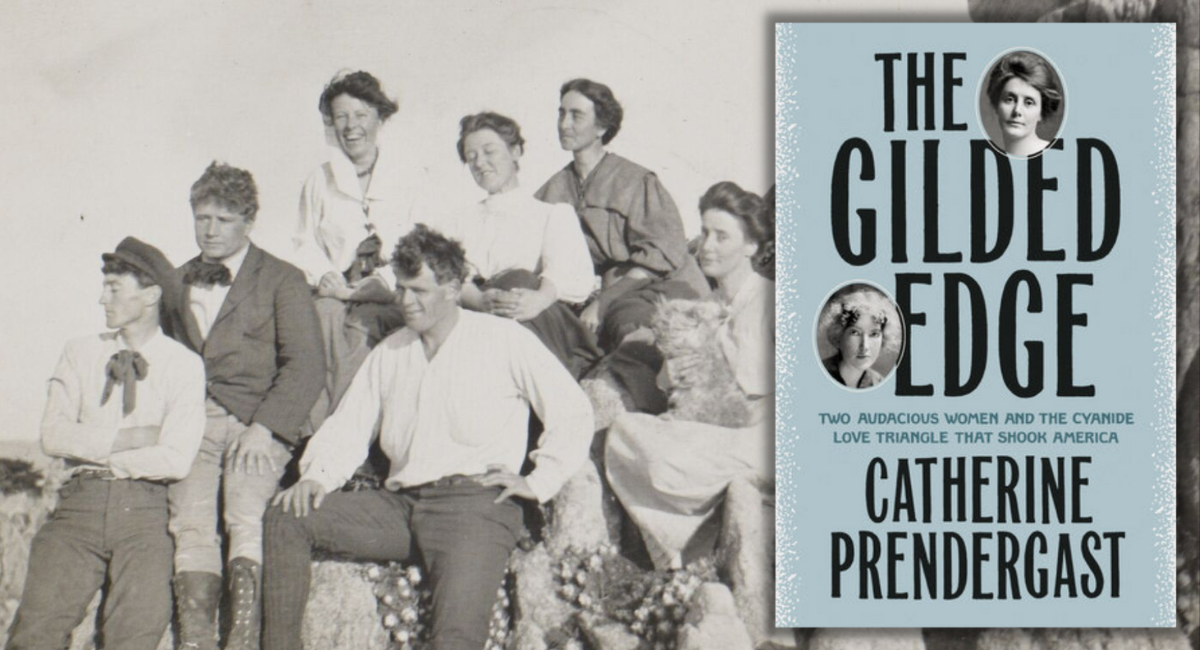

On the West Coast during the early years of the 20th century, a small group of male writers presided over a Bohemian colony in the beach town of Carmel-By-The-Sea on the Monterey Peninsula. The men were surrounded by a constellation of women, as portrayed in agonizing detail by Catherine Prendergast in The Gilded Edge: Two Audacious Women and the Cyanide Love Triangle That Shook America (Dutton).

While feminism was ascendant alongside the reignited suffrage movement, the men of the Carmel colony exploited the women who dwelled in their circle. Their wives were “symbols of bourgeois conventions,” Prendergast observes, and their lovers were melancholy poets and artists, seduced and often abandoned to deal with pregnancies wanted and unwanted. “Scorned wife and elusive muse” — all expendable.

ILLUMINATING A DIFFICULT TIME IN AMERICAN HISTORY

This is Catherine Prendergast’s first foray into narrative nonfiction. A professor of English at the University of Illinois, she has taken a deep dive into an obscure story that illuminates a precarious time in American culture and business, especially real estate development in a region that had been shattered recently by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. One year later the Panic of 1907, centered in New York City, caused a global financial crisis. Art and literature endured, however. In fact, they flourished.

THE CYANIDE LOVE TRIANGLE MADE OF POETS

The love triangle of the book’s title is comprised of Nora May French, one of the beautiful unsung poets of her time; Carrie Sterling, who vowed to escape poverty but spent much of her life in service to her Bohemian husband and his guests; and George Sterling, Carrie’s husband and Nora’s sometime lover. George fancied himself a superb poet and existed largely in a state of lust and drunkenness.

In the space of just four months in 1907, the lives of Nora, Carrie, and George turned upside down. Perhaps that was inevitable with three disparate personalities inhabiting such close quarters, a small cottage and cabin in Carmel.

Carrie, who had grown up in her mother’s boardinghouse, found herself cooking and cleaning — angrily — for a stream of visitors. Nora wrote poetry, hiked, helped Carrie with chores and fended off admirers. George philandered. Occasionally he returned to San Francisco to balance the books at the real estate company where he worked. Always on the verge of going broke, he planned to make a fortune by establishing Carmel as an artists’ community.

A CAST OF ARTISTS, WRITERS AND FRIENDS

Swirling about the trio were novelist-adventurer Jack London and his wife Charmian, the literary critic Ambrose Bierce, and the author and muckraker Upton Sinclair. Lesser-known — also coming and going around town — were playwright and naturalist Mary Austin, poet and realtor Harry Anderson Lafler, and a novelist and former UC-Berkeley football star, Jimmy Hopper and his wife Mattie.

The group posed for photographs, dove for mussels and abalone, flirted daringly and burned the candle at both ends, to paraphrase the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, a star of Bohemia on the opposite coast in Greenwich Village.

Meanwhile, Nora hoped for happiness, Carrie for a loving, stable marriage, and George for fame and more conquests. Instead, Nora gave up in despair, Carrie eventually gave up on George and left for good, and George entered a drunken stupor from which he would never emerge.

All three committed suicide by poisoning themselves with cyanide: Nora in November of 1907, Carrie in August of 1918, and George in November of 1926. I will leave the awful details to the reader, but there is much more to the book.

AUTONOMY GIVEN TO WOMEN IN THE NARRATIVE

The Gilded Edge unravels a tragedy that was shocking in its time, and the author could have simply retold it to shock a 21st-century audience. But Prendergast approaches the story personally. She shares her own experiences of being diminished by men because she is a woman. And she asks why Nora May French, Mary Austin and so many other women artists are lost to history while men of little or no talent continue to appear in the literature.

In pursuit of a great subject, research can be thrillingly like detective work as one peels back the layers and uncovers new information. As Prendergast visits archives and follows the trails of letters and diaries, she often finds that the women’s side of the story has been obscured or buried. Occasionally she interrupts her own narrative to fit the pieces together.

“Allow me to correct the record,” Prendergast writes in her prologue. Indeed she does in this engrossing and surprising book.

A Q&A WITH CATHERINE PRENDERGAST

How did you find your way into this web of disappointment, chauvinism, nascent feminism, and mystery? Did you come to it via history or literature?

I noticed that all these coffee table books were coming out around the same time, extolling the centenary of this or that arts colony founded in the first decade of the 20th century. And in each instance, what I call “second-tier robber barons” had been behind the creation of these colonies: buying up depressed land, designating its use for artistic purposes, recruiting people to join in their cause.

These were not people with Rockefeller or Carnegie money. They didn’t have enough wealth to create the great public institutions in New York. But they had enough to do this. But I began to wonder, why did they do it at all? Why are all these city folk buying up depressed rural land at the same time? Why is all that rural land so cheap just at that moment? What if we look beyond altruism as a motive and actually investigate what was happening in each location?

By 2014, I had begun preliminary research on several of these colonies, but when I found Nora May French and the arresting story of her life and death, it broke the book I had carried in my mind, and The Gilded Edge took its place.

The book addresses social and cultural change, especially among women. Would you talk a bit about the “New Woman” and how her emergence at the turn of the 20th century inspired and influenced your work?

The “New Woman” was the term for women between the 1880s through the 1910s who ventured out of their constraining domestic roles in one way or another to do something in public.

For the first time, middle-class white women were en masse entering the workforce, participating in politics, riding bikes and publishing in magazines. Women were suddenly to be seen as forces in the world, and were unapologetically confident. These women had great expectations that their lives would be different from what their mothers had experienced.

As I note in the book, however, when the New Woman emerged, there was no New Man to greet her. Just the same old, same old man with the same expectation of what a woman would do for him. The good news: Even though the backlash against women’s calls for greater independence was sustained, a good enough head of steam had developed through this period to secure the vote for women by its end.

Did you decide in advance to include your own story alongside those of Carrie Sterling and Nora May French, or did it just happen as you started to write?

I tried to write a more traditional history at first — I really did. But half the story was about how feverishly the men around Carrie and Nora had worked to shape how these women would be remembered. The men who outlived them decided what made it to the archives, and what didn’t. They were the ones who excluded pages from letters, or rip portions of them off, or scratch through words.

I had to piece the fragments together to find Carrie and Nora. Like any puzzle, the fun is in figuring it out. I decided I didn’t want to deprive my readers of the thrill of discovery that I experienced in working out the lives of these women from the available clues. So in the chapters where I take the reader into the archives with me, they get to encounter some of the same documents I did and decide for themselves what they mean.

After Nora’s suicide, Jimmy Hopper wrote to George Sterling: “…she was playing toy with us tangle-footed blunderers…” Do you think Nora toyed with her suitors or they with her — or both?

In the wake of Nora’s death, Carrie says of her, “She played the game.” And by that, she meant one thing: the game of women acquiring men through sex. Nora was not playing that game, however. Had securing a man been her aim, she’d have married any of the men who offered her a comfortable life through marriage. She could never bring herself to marry, because doing so would mean sacrificing her freedom.

No, she wasn’t playing. She was just living. But even if we want to look at sex as a game, it’s clear that the stakes of that game are life and death for women, and remarkably low for men.

Your passion for archival research shines through. In the course of your previous scholarship, have you ever dug so deeply? Do you have a favorite research library?

Every archival project brings its own challenges. Permissions are always an underappreciated aspect of the work. When a decade ago I was writing about the Unabomber’s lawsuit to get his writings back from the FBI, I corresponded with him to get his permission to quote from his correspondence and manifesto drafts. And then I wound up on his Rolodex and got the odd letter even years after, for example, alerting me if he’d done a new interview that had been published.

When you do archival work, you’re really establishing some kind of relationship. And that’s essential, because for me, the most intriguing archives are always the ones off the map: in someone’s attic, or in a town hall basement where they really don’t even know what they have.

And you have to explain why you want it, and that moment is always fraught with possibilities — or collapse. Who am I to ask for access to something of theirs? Something often quite personal? Even when I am in a research library, where the material has long since been turned over to prying eyes, I feel this question in the background of all I do.

As for my favorite research library, it is whichever one holds the papers that I need right now. I appreciate all librarians and archivists more than I can say.

You are a professor of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Do you teach American literature? If so, what is your particular area?

My teaching interests are broad and do include both American and British literature. But my most enduring interest, regardless of the subject I teach, is in students and what they have to say.

I think of them as producers rather than merely consumers of knowledge. In every class, I invite students into a process of discovery, one in which I am going to learn something by the end of the course as well.

Could you tell us about your next project?

I’m stuck on the way Jewish women’s leadership has been co-opted and written out of the story of American socialism and labor organizing. And there are some women in that category I want to give their due.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Catherine-Prendergast-454×550.jpg

About Catherine Prendergast:

Catherine Prendergast is a Professor of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, a Guggenheim Fellow, and a Fulbright Scholar. Interviewed by NPR and New York Magazine, she has written on battles over school desegregation, anxieties over the global spread of English and recognition of disability rights. Originally from New Jersey, she can now be found amidst the cornfields of the Midwest with her husband and son.