East of Troost by Ellen Barker

It’s the story of countless American cities. A harsh line severs the community, cutting Black residents off from more affluent white neighborhoods. Those who do venture across are at risk of being met with threats, violence and displacement. Whether the line was established during the segregation era or was quietly installed afterwards is only one part of the troubling equation. Regardless of its year of origin, it’s an undeniable part of city life that often goes unspoken by the well-off.

Author Ellen Barker dives into the story of one such line in her book East of Troost (She Writes Press). Inspired by her own childhood in Kansas City, Missouri, Barker describes how the construction of Troost Avenue irrevocably changed the lives of Black families on the eastern side of the parkway. As the book’s white narrator moves back into her childhood home on the east side of Kansas City, she must reckon with neighborhood’s complicated history, and how long-held prejudices continue to endure right through to the present. Empathetic and ever-relevant, East of Troost is a detailed story of one city that will resonate with communities far and wide.

Q&A WITH ELLEN BARKER

Q: Where did the idea for this book come from?

A: I grew up in Kansas City, Missouri in the 1960s. I was a white kid living east of Troost, the de facto dividing line between Black and white areas. The east side, where Black families were just starting to buy homes, was changing quickly and it wasn’t going smoothly — no surprise, given the racist rhetoric and long-held prejudices. I went to college, my parents retired to a small town and I never went back until forty years later. It was clear that the neighborhood had never recovered and was now split by an expressway. I wanted to write about how “East of Troost” came to be a place, and I wanted to restore my childhood home, at least on paper.

Q: A key theme in the book is subtle racism today and overt racism in the past. Please elaborate on how these issues are addressed.

A: The white narrator of the story moves into her childhood home in the present and gets a close-up view of what racism in the past created and how it remains — sometimes explicitly and sometimes just in the looks she gets when she tells people where she lives. As she builds a new life, she looks back on her childhood and recalls specific events nearby: Black families burned out of their homes, houses being taken over for the expressway and left vacant to harbor rats and squatters, rioting following the Martin Luther King assassination. Since East of Troost is told in first person and present-tense, we see her react to both past and present.

Q: How was the fictional narrator inspired by your own experiences?

A: Most of what takes place in the past is very close to what I remember. What takes place in the present century, as the narrator rebuilds her life, is what I imagined it would be like to experience a life-changing event that prompted me to move from my comfortable California life to my childhood neighborhood. Some real events found their way into the present-day narrative, such as the first trip to the childhood church and the drama in the cell-phone store, although that one happened to a friend in an entirely different city. The gut fear comes from memories of my own life, including a burglary and a middle-of-the-night home invasion when I lived in Massachusetts.

Q: Explain the literal meaning of “Troost” in the book title and what it stands for figuratively in the book.

A: Troost Avenue is a north-south street in Kansas City. It served as a dividing line of racist segregation and disinvestment, with white residents living west of Troost and Black residents living to the east. Red-lining, deed restrictions and lending policies all shored up the “Troost Wall” as it is sometimes called. “East of Troost” is still in the lexicon of Kansas City. One of the points I want to make, though, is that the Troost wall is not an anomaly. Most American cities have one, although in some cities they are more blurred now. In Kansas City, the expressway was thrust through the neighborhood that Black families were moving into. In many cities, interstate highways were used as hard-to-breach boundaries.

Q: The book spans the basics of human behavior: compassion and cruelty, fear and courage, comedy and drama. How do you tackle such wide-ranging themes?

A: I wrote the book in first-person, present tense. So the reader goes through the story in the head of the narrator, hearing and seeing and feeling what she hears and sees and feels. She experiences those things, as we all do, with some added drama of living in a fraught period of her life, and of course with the freedom that fiction provides of compressing a lot of events into a short period. In this case, the narrator also gets to pull in remembered cruelty, fear and drama (e.g., white teens burning houses of new Black residents). And since we’re inside her head so much, we see her internal conflicts, especially between fear and courage. And the dog adds a regular dose of comedy.

Q: What would you hope readers to take away from this book?

A: I want them to enjoy the book first of all, so that it stays with them. And I hope that something in it stirs some memory from their own lives that they can connect to these themes and expand their understanding. In particular, the realization that fear begets hatred and that leads to violence. The things we do today, good or bad, conscious or unconscious, have a lasting impact. And maybe some of them will take a drive to an “other” part of town and have a meal or take in a play or get that oil changed.

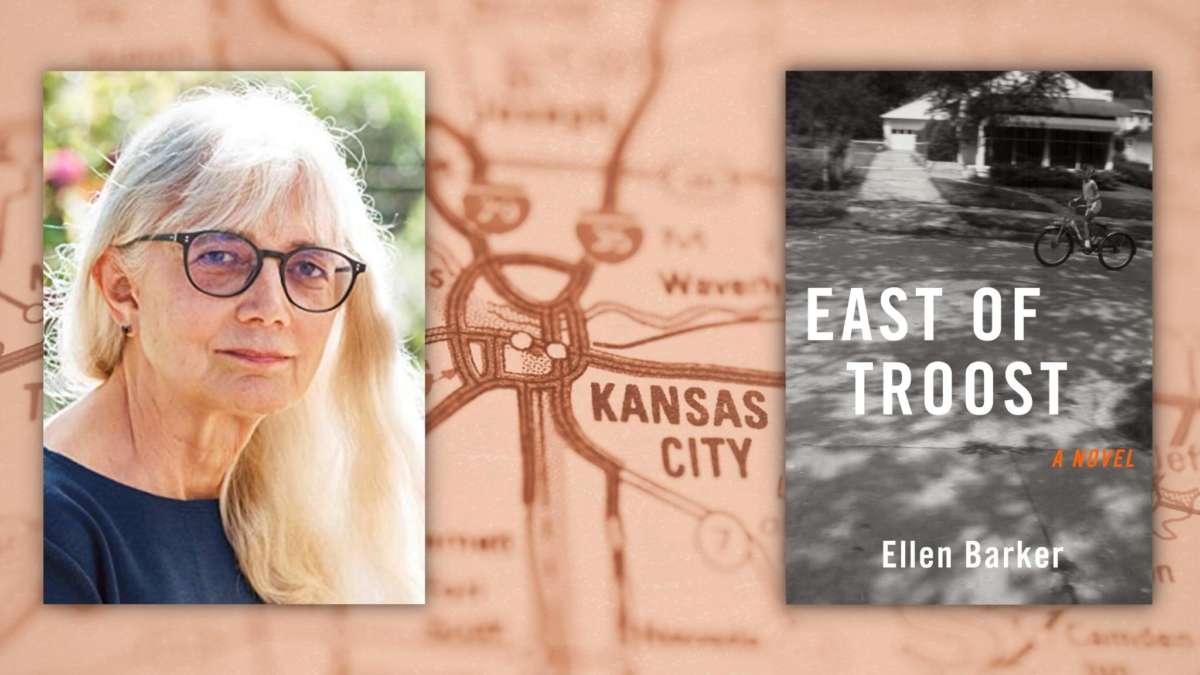

About Ellen Barker:

Ellen Barker grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, and had a front-row seat to the demographic shifts, the hope and the turmoil of the civil rights era of the 1960s. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Urban Studies from Washington University in Saint Louis, where she developed a passion for how cities work, and don’t. She began her career as an urban planner in Saint Louis and then spent many years working for large consulting firms specializing in urban infrastructure, first as a tech writer-editor and later managing large data systems. She now lives in Northern California with her husband and their dog Boris, who is the inspiration for the German Shepherd in East of Troost.