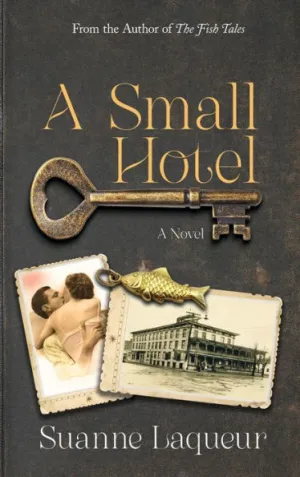

A Small Hotel by Suanne Laqueur

Suanne Laqueur’s ambitious historical fiction novel, A Small Hotel, begins with a “Once upon a time” innocence, a sweet simplicity that belies the labyrinthine journey she’s about to take her readers on. It’s a romance; a travelogue; an introduction to Swedish mythology, language and good luck charms.

The story begins during World War II — before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The Fiskare family are living an idyllic life on the shores of the St. Lawrence River, minutes from the Canadian border and surrounded by the river’s Thousand Islands.

Their home is a stately hotel, established and run by their family for decades, and named after the family. Fiskare is Swedish for fisherman, but the locals insisted on calling it the Fisher Hotel. “Rather than correct their neighbors,” writes Laqueur, “the Fiskares simply repainted the sign:”

THE FISHER HOTEL

Est. 1895

The hotel, the grounds, the bucolic islands, the water and storms are as integral to the story as are the family and their visitors, and Laqueur wastes no time getting her readers engaged. The tight extended family is handsome and trim: the widowed Emil and his brothers Major and Nyck, Emil’s children Little, Trudy, Kennet, Minor and Nalle. And there’s Marta, their cook, nanny and the closest thing to a mother the children have had since the death of their own mother.

A WORLD WHERE LOVE IS ALMOST PAINFUL

The Fiskares open their home to those who need one, so there are visitors and lodgers who become almost family. Soon, readers will wish they, too, could go to Clayton and check in to the Fisher Hotel. Loving the characters in this book comes easy and quick, and plots unravel swiftly and tangibly. It is a world where love is almost painful, heartaches are raw, but the joy is beautiful and uncontainable.

Kennet falls in love with a photograph of a Swedish girl on Marta’s dressing table, which comes to life when Astrid steps off the train. Like the glance over her shoulder in the photograph, Astrid’s eyes say, “I know you.” And Kennet wants to say, “I know.” He wants to say that he has already fallen in love with her. Their connection is sure and solid, but circumstances will break both their hearts.

Laqueur is a fine writer, dropping little inside jokes and familiar family phrases throughout, using marvelously idiosyncratic similes and metaphors. When describing Nalle, who is dark-haired and brown-eyed unlike his blue-eyed family, “It was as if every gene of the Fiskares’ French-Canadian ancestors saw in Nalle a chance to survive and swarmed his cells like ants on a melon rind.”

A Small Hotel is lively and highly readable, almost musical. Indeed, Laqueur inserts song lyrics from the ‘40s and parodies of nursery rhymes among the story. But what begins as a book of family lore and sweet complexities takes a sharp turn in Part Two when the Fiskare boys go to war.

EXPERIENCE THE UNSPEAKABLE

Here, Laqueur’s writing becomes sharper, edgier. The horrors of war are not spared. In his journal, Kennet writes down the unspeakable; he experiences the unthinkable; he does the unimaginable. War is appalling; battles are swift and bloody. Soldiers are dirty and smelly and hungry and scared. Laqueur leaves nothing out. Not even the stench and horror of the hellscape of the concentration camp Kennet must visit.

The aftermath of war is not easy, either, sorting out the dead, the wounded, and the irreparably sad, but the Fiskares are solid. Not stooping to a fairytale happy ending, Laqueur scrapes up what remains and makes the best of it. So much so that when her readers read the last few pages, they are reminded of tiny golden fish, a tooth, a Zippo, nails tossed in the river, and the taste of chocolate — and when there is that, perhaps, like Kennet, we might feel we have everything.