Patti Smith. Simone de Beauvoir. Cynthia Ozick. Sonia Sanchez. J.K. Rowling. What do all of these have in common?

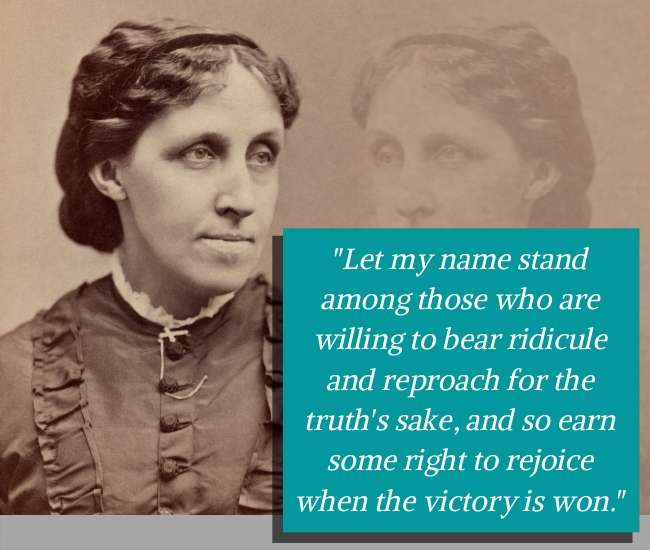

When Louisa May Alcott set out to write her most cherished work, Little Women, could she have foreseen the impact it would have on generations of women writers, even to this day? This novel, and the ones proceeding from it, presented us with the role model of Jo March — tomboy, independent thinker, writer. Time and again, Alcott and her fictional heroine have been cited as influences and inspirations by women writers as diverse as those mentioned above, and then some.

But what many of us don’t know is the role that Alcott and her family played on a much bigger stage in paving the way for all women. As we wind down Women’s History Month in a year that heralds the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, BookTrib has invited Alcott expert Susan Bailey to provide us insight into this aspect of Alcott’s legacy.

In March of 1880, nineteen women voted for the first time in a town election. Two of those who cast their ballots were sisters; the younger was a famous author. That author, the first woman to register, was Louisa May Alcott. The town was Concord, MA, and the election was for the local school committee. Louisa voted with her older sister, Anna Alcott Pratt.1 For Louisa and Anna, the most important accomplishment was their taking that first step towards fulfilling their mother Abigail’s long-cherished dream of women’s suffrage.

Abby May Alcott, Louisa’s mother

Abby May Alcott, Louisa’s mother

Born in 1800, Abigail “Abby” May Alcott was the youngest child of a prominent Boston family which included Mays, Sewells, Quincys and Hancocks. Abby’s parents, Colonel Joseph May and Dorothy Sewell, passed down to their daughter a passion for reform along with a strong sense of duty towards those less fortunate. As a single woman, Abby wished to defer from marriage to become a teacher. Having been denied the formal schooling of her brother Samuel Joseph because she was a woman, Abby continued to study on her own. Her dream was to open a school with her sister Louisa with the idea of educating other women.2

While that dream did not come to pass, Abby found a like-minded companion in progressive educator Bronson Alcott. She had hoped to teach by his side but instead became his wife. Although she loved Bronson and supported his work with great enthusiasm, she was keenly aware of her reduced status as a married woman. Alcott biographer Eve LaPlante writes, “Under the English common-law principle of coverture … the husband and father owned his wife and children. A divorced woman lost all rights to her children, including custody, because children were a husband’s property … Married women held no property in their own right and were not entitled to their own wages.”3

Because of Bronson’s inability as a provider, Abby was forced to become the breadwinner. Employed as one of Boston’s first social workers in the early 1850s, her meager wage could not support the family. Eldest daughters Anna and Louisa were pressed into service as soon as they were of age, working as teachers, governesses and servants in the homes of wealthy relatives. Abby, meanwhile, took in boarders to make ends meet, depending upon younger daughter Lizzie to assist with the enormous amount of housework.

Orchard House in Concord, MA, the Alcott family residence from 1858 to 1877

These difficult years of working to fight off chronic poverty fueled Abby’s passion for women’s rights. In 1853, she penned the first of her petitions, submitted to the Massachusetts State Legislature, demanding suffrage and equal rights. Her words ring with authenticity: “Crowded now into few employments, women starve each other by close competition … Open to women a great variety of employment, and her wages in each will rise; the energy and enterprise of the more highly endowed will find. And honest effort, and the frightful vice of our cities will be stopped at its fountain-head.” Despite the fact that her petition was signed by 73 women, her husband, her brother (prominent Unitarian minister the Reverend Samuel Joseph May), the abolitionist Wendell Phillips and the Reverend Theodore Parker among others, it was promptly dismissed by the legislature.4

Abby realized this was just the first step in the fight for women’s suffrage and knew she would have to engage her daughters in the fight. Especially close to Louisa, she counseled her: “Be something in yourself, let the world know you are alive!”5 Several years later, Abby would see Louisa succeed beyond her wildest dreams as the best-selling author of Little Women.

Using her fame, Louisa would carry on her mother’s fight, organizing meetings to encourage and educate women on the vote, and contributing her writing to Woman’s Journal, edited by Lucy Stone.6 In that magazine, she would describe that fateful day in 1880 when she and sister Anna cast their vote in Concord. Having passed away three years earlier, Abby could not witness the event. But her husband said it best as he watched his daughters with pride: “[I am] much gratified in the fact that my daughters are loyal to their sex and to their sainted mother, who, had she survived, would have been the first to have taken them to the polls.”7

1LaPlante, Eve, Marmee and Louisa: The Untold Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Mother (Free Press, a division of Simon and Schuster, 2012) pg. 269

2Ibid, pg. 28

3Ibid, pg. 105

4Ibid

5Ibid

6Alcott, Louisa May (author) Myerson, Joel (editor), Shealy, Daniel (editor), Stern, Madeleine B. (associate editor), The Selected Letters of Louisa May Alcott (University of Georgia Press, 1995), pgs.245-246

7Marmee and Louisa, pg. 269