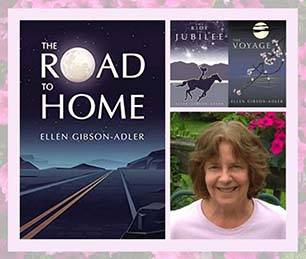

“Much of my fiction revolves around the theme of resiliency and the internal work it takes to overcome being different,” says novelist Ellen Gibson-Adler. “In other words, taking what life throws at you and not just surviving, but thriving, in spite of obstacles.”

In her Lyons family trilogy, Gibson-Adler explores the ways flawed and hurt people find their way through these obstacles to achieve redemption and fulfillment. The three novels in the series create a story arc that starts in the middle, as it were, with the childhood and coming-of-age story of protagonist Nelle (The Ride to Jubilee), then hops backward in time for a prequel that tells the tale of Nelle’s parents and how her family situation came to be what it is (The Voyage), and then finally back to Nelle as she develops the emotional maturity needed to handle the responsibilities of adulthood (The Road to Home). Taken together, the series is a powerful and haunting portrayal of one family’s tapestry woven together with history, war and vulnerability.

We had the opportunity to chat with Gibson-Adler via email about her series and the characters within.

Many of your characters are deeply flawed or damaged by their experiences. Which character, in your opinion, had the most to overcome and why?

Maggie, the mother of Nelle, is the character who had the most to overcome and is the main character in the second book of the trilogy, The Voyage, which is a prequel to the first book, The Ride to Jubilee.

Maggie was a young woman who left her small town of Framingham, MA, to join the fevered war effort by accepting a job in Washington, D.C., at Western Union right after high school. She fell hopelessly in love with the handsome Army officer Terry Alexander and was thunderstruck by not only his good looks but the chance to travel and see the world, which fulfilled her keen sense of adventure. Maggie was beautiful, talented and fearless, but had no idea what leaving home, traveling to a war-torn country, and adjusting to a man who had deep scars from his own flawed family meant.

While Terry is stationed in Tokyo, Maggie had the friendship and daily support of their “house girl” Michiko, who cared for Maggie’s two little girls, Mary Ellen and Nelle. Michiko, a war victim who lost her family in the Hiroshima bombing, spoke little English and was destitute before coming into Maggie’s household. They bonded over the shared reality of trying to make a new life in an unfamiliar world. Michiko’s friendship gave Maggie the daily support and affection that she had missed since leaving home and marrying into a military life that also took a tremendous toll on her young husband.

But upon Terry’s re-assignment to Alaska, she had no such support. The military drinking culture offered camaraderie and a sense of shared mission and togetherness. It was there that Terry became increasingly absent and violent when he drank to excess. Maggie’s loneliness grew as she found herself solely responsible for the care of her two girls.

When the third daughter came along, Christine, after Terry’s transfer to the military base in Texas, Maggie had to cope with another unfamiliar and unforgiving environment. Here she was again as an outsider “Yankee” in a “foreign” place. Without maternal support and guidance from her own mother and little knowledge of “family planning,” the birth of her children in quick succession had overwhelmed her. Army bases had no resources for young, struggling mothers.

She was lost, depressed, and her loneliness shoved her into dark, regrettable places. She drank. Though she suffered emotionally, Maggie never gave up hope that Terry would somehow get better and come back to her. For all of Maggie’s bad behavior – the men, the booze – she held on to a spark of light that somehow she could climb out of her deep well of disappointment for the sake of her girls. Motherhood, for all of its difficulty and heartache, held the promise of a future that she could aim for, but she knew she had to do it alone. And she did, for as long as she could.

Her girls were always the center of her life and her longing to have them thrive and prosper and to grow up with a sense of security and safety was the driving force that finally made her realize that she couldn’t give that to them and neither could her damaged warrior husband Terry. So, she left them out of love into the care of their grandfather and fled in an attempt to regain her own dignity.

Despite her unraveling, Maggie never lost her essential self. She carried a kernel of belief in herself and embarked on a pilgrimage to “get herself together.” When she realized that Terry could never become whole, she knew she had to. Maggie always wanted to return to her girls, but she had to be right and well before she could do it. Her pilgrimage taught her that forgiveness, beginning with herself, was the freeing of spirit that comes with the grace of releasing the hurt. In the end, Maggie found the freedom to live a light-filled life and returned to her girls.

Throughout this family’s story, there are themes of resiliency and redemption that take different forms for different characters, sometimes in subtle ways. For example, how does this apply to Nelle’s dad, Terry, who has been institutionalized for PTSD and psychosis?

Terry ran away from home and joined the service to flee the terrible unhappiness he suffered as a child living in a home with a seriously disturbed mother and a largely absent father. He had no reference in his young life, as a boy on a sharecropper farm, for contentment, stability, security and happy family times. His mother’s psychosis broke him early on, and his horrific war experience, captured graphically in The Voyage, shut down any ability to overcome the pain of memories and hope for a “normal” life. Authors have written about “shell shock,” PTSD and the ravages of war forever. The acronyms do little to deepen understanding for those ruined by war. Terry never recovered from WWII.

Oddly, but not uncommonly, some people adjust to institutional life and find a certain peace through the regimented, no-surprises, place to eat and sleep existence offered there. Terry actually carved out a pretty good life for himself given what he had suffered. He gained respect from his fellow men, developed meaningful relations with his crow buddies in the garden (a real phenomenon, by the way, for many people), and did not have to worry about being the responsible head of a family.

Animals figure prominently in your work, especially horses. What role do they play in the lives of your characters and within the themes of your novels?

Animals offer a connection to a larger sense of the universe beyond the language and foibles that human beings get jumbled up in. In many cultures and settings, whether on an Indian Reservation, on a farm, in China, Argentina, India and all across Asia, animals give and take love unconditionally. Horses, in particular, are known for their quiet, almost telepathic relationship to sympathetic humans. Horse therapy is mainstream now. Many souls have known this fact forever.

Maggie’s dog, Pal, followed her to school every day and lifted her from the worry she had over her alcoholic father. Nelle’s first love affair was with John Bananas, a stray kitten that filled her heart with unspeakable joy. Nelle finds refuge in nature and especially in her connection to horses. In the first story, through visiting a magnificent black stallion corralled alone in a pasture, she came to realize that circumstances don’t have to take your personal power. She saw a glorious, intelligent horse, that came to her each time and offered affection and imparted strength and hope. Every time she left him she felt better and realized that someday she would be able to overcome the life that corralled her, too. And, of course, Nelle’s relationship to the pony Hot Shot enriched her life beyond what any person had given her.

Almost all of my characters derive comfort from the love of animals, without words, without expectations, without demanding anything back. This has been true in my life, too. They elevate the human spirit and show us the power of love.

If you were going to write a fourth book in the series, who or what would it be about? What threads of the story do you feel are still wanting to be told in deeper detail?

If I write a fourth book in the series, it will tell the story of Nelle and Pete growing into parenthood and it will involve the themes of ecological awareness, civic action, changing values and a new generation of young people coming along with their different dreams and aspirations for a better world. It will talk about the wounded warriors and their struggle to re-enter society, and it will look at the new progress and challenges that indigenous people grapple with as the world continues to change from generation to generation. I will look at aging, the joy of it, the privilege of it, and the heartbreak of it. I will develop characters who become addicted. Some will overcome. Others will not. I will write about the beauty and sorrow of living and how every season is a gift to cherish and memory to hold dearly. And animals will take their rightful place beside us to guide us through this all-too-short adventure.

—

Whatever characters populate Gibson-Adler’s next work — be they Lyons or not — they’ll surely take us on new journeys of the self, struggling through their flaws (and consequences of those flaws) to find redemption and forgiveness, but most of all, a place in our hearts.

Learn more about Gibson-Adler on her BookTrib author page, and read our review of The Road to Home here.

https://booktrib.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Ellen-Gibson-Adler-300×300.jpg

About Ellen Gibson-Adler:

Ellen Gibson-Adler was born in Tokyo during the American military occupation of Japan following WWII. She grew up in the nomadic travels of a military family, which took her from Japan to Alaska, Ohio, Texas, Louisiana and Massachusetts. She graduated with honors from the University of Massachusetts at Boston with majors in anthropology and sociology. During her long career in public service in Massachusetts and Maryland, she served with non-profit organizations and government institutions focused on environmental, social action, educational and criminal justice missions.

The Road to Home is her third and final novel in the trilogy beginning with The Ride to Jubilee and The Voyage that chronicles the saga of the Lyons family. It concludes with a powerful and haunting portrayal of how history, war and vulnerability weave of a compelling family tapestry. She resides in Maryland with her husband.