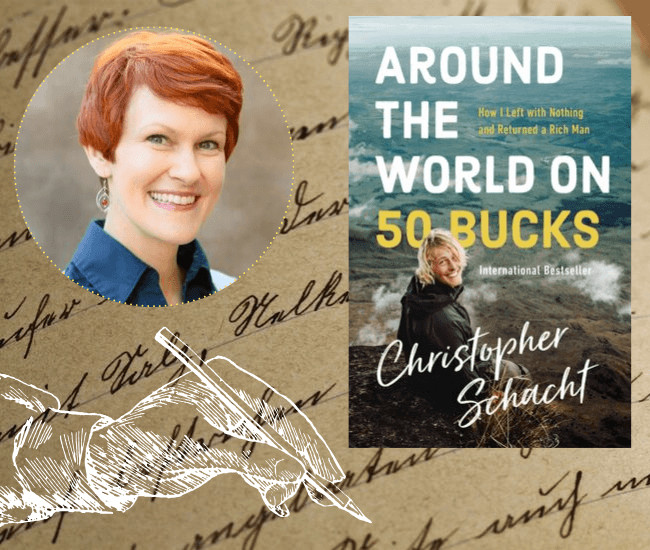

Tracking some 65,000 miles and 45 countries, Christopher Schacht’s international bestseller Around the World on 50 Bucks (W Publishing Group) recently became available in English, thanks to a translation by Janet Gesme.

Translating a book into a different language is something to which most readers probably don’t give a thought. Yet it’s quite a process. We recently had the chance to interview Gesme, who provided us with some fascinating insights.

How does a U.S./English-speaking audience differ from a European/German-speaking one?

The German speaking audience is typically more patient and willing to read longer texts to absorb an idea. Therefore, I usually have to consolidate the German text to “get to the point” for English readers.

But that was not the case with Christopher Schacht’s book. He writes quick, exciting, short stories that make you laugh and make your eyes pop out in surprise. There was simply no need to alter the style: his writing is exactly what an English-speaking audience loves.

What were the particular challenges or joys of translating Around the World on 50 Bucks?

First, we were on a short timeline, so I needed to translate the whole book in three months. That meant a lot of late nights. The second challenge was Christopher’s sense of humor. He is hilarious! But some of his humor is based on German idioms that are very hard to translate.

This leads into the joys: Christopher and I skyped on a weekly basis while translating the book. We brainstormed together on how to find English equivalents for the German style of silliness.

What made you choose this project in particular?

Although I have been translating and interpreting German, Russian and Spanish for years, I actually never planned to translate books. The first book I translated was Martin Schleske’s The Sound of Life’s Unspeakable Beauty. Prior to that, I was a professional violist. Injuries from a car accident landed me in bed for the better part of two years, and I was forced to give up playing the viola. During this time, I started translating The Sound. After a year of feeling well again, I got an email from a publisher asking if I was interested in translating Christopher’s book.

I was flattered, but of course I had to think it through. I read the German version and then called Christopher. After telling him about my very limited experience, he started talking about his philosophy regarding translating. It resounded deeply with my own goals as a translator. Both he and I believe that rather than translating a passage word for word, a translator should fully understand the author’s intentions and then express each idea in the author’s voice, pretending that the author was born speaking English.

How closely did you work with the author? Take me through your process.

As I mentioned, Christopher and I skyped on a weekly basis. Since I was on such a tight deadline, I translated as much as possible each week and noted any questions that I had. I would normally research my questions and find the answers on my own, so it felt like cheating to simply ask Christopher each week what in the world he was talking about. His English is excellent, so he would often just tell me the English word for the odd bit of equipment or cultural artifacts. If he didn’t know how to say it in English, he would send me a picture, and I knew immediately what he was talking about. I always go through the text multiple times, often reading it out loud to get the flow. With Christopher’s book, this was ridiculously entertaining.

One of the themes of this book is communicating through barriers. From your professional standpoint, how would someone interested in traveling best pick up a new language in a strange place?

Christopher has great tips for this in the book: Use apps and dictionaries to learn as many words ahead of time as possible. When traveling, you often have to wait a lot. This is the perfect time to learn. Then dive in and talk to people. You will make mistakes and it will be hard, but it is so worth it.

This book includes a section on the Warao people who the author describes as having a very plentiful and relaxed lifestyle. Schacht also describes their language as having “barely any grammar.” Is there any correlation between a community’s lifestyle/culture and their language? Is this reflected at all in German?

Oh, yes, there is a huge correlation between grammar, vocabulary and culture. Take Korean, for example. Rather than conjugating verbs according to the person doing the action (I go, he goes), they conjugate based on the social status of the person being addressed. There are four levels of formality in regard to age, status, and other aspects of the relationship. There are also two words for “I,” one that places you above your conversation partner and another that places you below. There are different words for “person” as well, and it is never socially appropriate to refer to yourself with the highest form of this word, “pun.” Humility, respect based on age, and social conventions are deeply ingrained in Korean culture. This is very difficult for English speakers to understand and master.

Then there is Spanish. All emotions trigger the subjunctive case. The topic of grammar and culture is rich and full of inexhaustible examples. The more you learn about other languages, the more you understand your own culture and how it is affected by grammar.

About Janet Gesme:

I’m Janet: translator, musician and mother of two. I play string instruments and speak English, German, Russian, and Spanish. (Feel free to write me in French and Hungarian as well!) Check here for updates on my current translating project, Martin Schleske’s Der Klang (The Sound) as well as foreign language activities and concerts.

I’m Janet: translator, musician and mother of two. I play string instruments and speak English, German, Russian, and Spanish. (Feel free to write me in French and Hungarian as well!) Check here for updates on my current translating project, Martin Schleske’s Der Klang (The Sound) as well as foreign language activities and concerts.