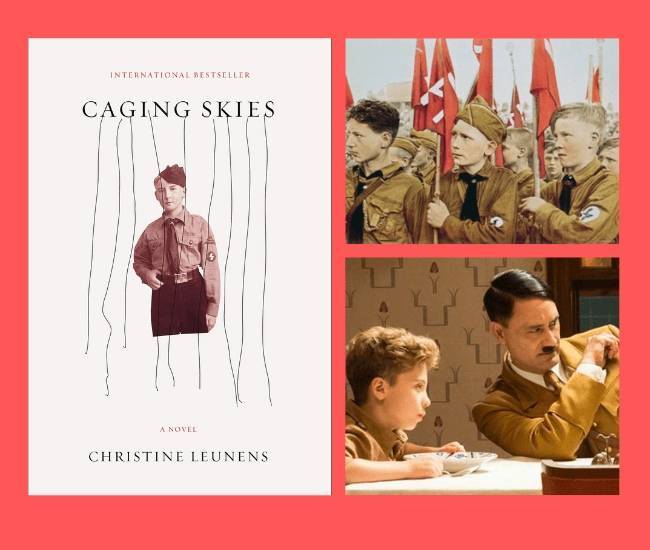

In WWII-era Vienna, a little boy named Johannes learns to be proud of his Aryan face and burgeoning strength. After joining the Hitler Youth, Johannes’ whole sense of purpose revolves around fighting for Adolf Hitler. That is, until he becomes disfigured in a bombing raid and then finds his parents hiding a Jewish girl in his own house.

There is no help for the reader: it is an aching journey, sometimes funny or heartwarming, other times horrific. Reading Caging Skies (The Overlook Press) traps the reader in the mind of Johannes as he ages, demonstrating that sometimes the things–and people–we love most become our cages.

As the book makes its U.S. release this month, with a film adaptation from Taika Waititi called Jojo Rabbit slated for October, we had the chance to ask author Christine Leunens about the book, the movie and their various themes.

For a book that is so sad and intense, how did you feel about the movie adaptation being heavily satirical?

In the book there are some elements of comical relief from the grandmother, who is unaware of Elsa living under the same roof, and Johannes’ youthful awkwardness and ruses that backfire. Taika Waititi and I both seek our own balance of drama and humor, he leaning more toward humor and I more toward drama. It’s often after a laugh that one’s feelings are drawn back to a sense of reality where things aren’t right, into deeper, sadder emotions, like the realization of the absurdity and tragedy of Johannes’ and Elsa’s situations. Without giving anything away, I will say there are moments when the audience cries too.

How do you feel the film will impact how people read the book?

Those who’ve seen the film first tend to visualize the book’s characters as they looked in the film. I just read Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind and imagined the characters with the same faces as in the movie. But other than the transposition of faces, readers will still have their own very personal experience of Caging Skies as they go from page to page, because the prose allows readers to go beyond a face and into a character’s mind.

Since the book was published in 2004, why do you think it hasn’t been published in the U.S. until now?

The world is changing incredibly fast, and I think people are feeling angst about the future, faced with digital disruption, climate change, mass migration, a collapsing ecosystem, economic instability. And add to that terrorism. People just aren’t feeling as secure as they were after the Berlin Wall fell. This coincides with a rise in racism and the far right. So sadly, my book has become “relevant.”

Johannes does not behave like the archetypal resister or enemy. When writing his character, did you always know where he’d end up?

Prior to commencing the writing, I already had in mind the historical structure of the novel – the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany, Kristallnacht, the compulsory Hitler Youth camps, war, defeat, the occupation of Vienna by the Allied forces. I also knew Johannes would lie to Elsa about Germany having “won the war” to keep her tucked away inside his house. However, I took Johannes’ journey day by day and let him live through these events and experience them each on his own terms, according to his own personality. That’s why he feels real to so many people around the world, because he experiences life on a smaller scale at home, school, camp, much the way we as real people do.

It is refreshing to see a character like Johannes that you are constantly doubting or sympathizing for. Why did you choose this angle?

It was to personally try and grasp what happened in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, and how something like that could ever happen. To this end it was vital for me to create a character who starts off essentially good yet flawed, like most of us, and who remains complex afterwards, sometimes getting it right, sometimes getting it wrong in ways that even he couldn’t have foreseen.

As the idea for this book dawned on me, Johannes crossed the fuzzy gray realm of my imagination as an eight-year-old flying a kite in the vineyards of Vienna, and before long was marching across fields in a Hitler Youth uniform. Now having seen him step out of the page, first onto the stage then onto the screen, I sometimes get the feeling that he lives very well on his own without me. Like a parent who wants the best for his or her child, it’s the best thing a writer could have hoped for a character.

From banned books to stylized paintings, art is a constant presence in the book. Do you agree with the character Pimmi that art is always made for someone else? Do you believe that art is a means of possession?

For art to be art, to me it has to be shared with and experienced by others, because it’s the response of “the other” to it that makes it art. There’s a connection between the viewer and the viewed, and it’s this connection, and not the object itself, the book or the painting in its completed form, that elevates it above paper and ink or canvas and pigment.

Art is therefore less a means of possession than a means of connection, one that erases the boundaries of time and geographical location and speaks to – or argues with, compliments, insults – our shared aspects of humanity.

About Christine Leunens:

CHRISTINE LEUNENS is the author of three novels translated into more than twenty languages. Caging Skies, an international bestseller sold in twenty-two countries, was shortlisted in France for the prestigious Prix Médicis étranger and Prix du roman Fnac. Born in Hartford, Connecticut, she has spent most of her life in Europe and now lives in New Zealand. She holds a master of liberal arts in English and American literature and language from Harvard University. A former model, Leunens was the face of Givenchy, Paco Rabanne, Nina Ricci, and others.

CHRISTINE LEUNENS is the author of three novels translated into more than twenty languages. Caging Skies, an international bestseller sold in twenty-two countries, was shortlisted in France for the prestigious Prix Médicis étranger and Prix du roman Fnac. Born in Hartford, Connecticut, she has spent most of her life in Europe and now lives in New Zealand. She holds a master of liberal arts in English and American literature and language from Harvard University. A former model, Leunens was the face of Givenchy, Paco Rabanne, Nina Ricci, and others.