Mud Season by Ellen Stimson

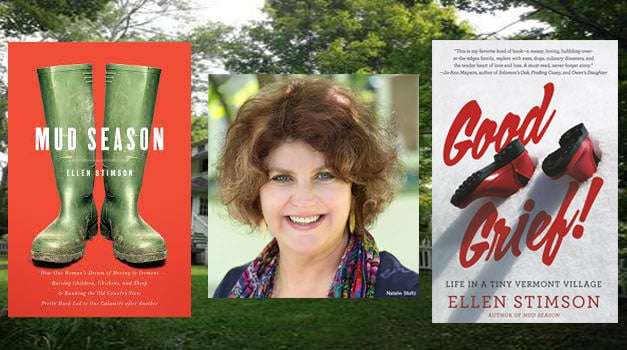

After a family vacation to Vermont, Ellen Stimson and her family did what most of us only dream about – they packed up their lives and moved to the mountains, fantasizing about small town life, green trees and chicken coops. They certainly got the trees and the chicken coops, but they weren’t quite as prepared for the bears, massive snowstorms and the general disaster of buying a quaint country store. Luckily for the rest of us, Stimson describes all of these events and more in her two hilarious memoirs about small town life, Mud Season and Good Grief.

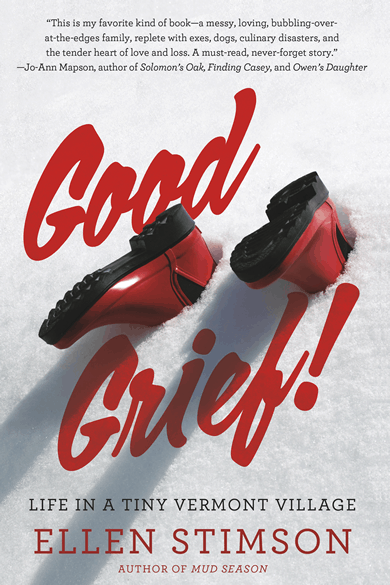

Mud Season, released in 2013, is a fish-out-of-water tale describing what it’s actually like to move to a rural town in the middle of nowhere. From unexpected wildlife in the front yard to that terrifying sound ice makes when it falls off the roof, Stimson turns an unflinching eye on her experiences, relating them all with self-deprecating humor. In Good Grief, newly released on October 6, we return to the same tiny Vermont town, though this time the story takes a tragic turn when Stimson describes the death of Steve, her first husband and father to her eldest son. Despite the tough subject matter, Stimson never loses her humor and wit, and her family is as charming as ever. BookTrib recently had the pleasure of chatting with Stimson about her books, life in Vermont, and what it truly means to lose someone you love:

BookTrib: In Mud Season, you moved to Vermont because of a fantasy but reality quickly took over. Was that line between reality and fantasy what prompted you to write the first book? Or did you know from the moment you moved to Vermont you would write about your experiences?

Ellen Stimson: What really happened is I was turning 50 years old. Fifty got my attention in a way no other birthday ever had. My mother had just died at 84 and I read an article that said that women who were born during the decade of the 1960s were living on-average three years longer than our mothers. But the last few years of [my mother’s] life had looked like a hot mess. So I thought, OK, if I do everything right I should be able to get to 80. I should have 30 more really great years. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke – cheese is kind of a hobby of mine, but except for that I thought I could get those 30 years.

Then I did the math. 30 years was 1,565 weeks and that didn’t sound like very much. I went to bed that night really bummed out. But I woke up in the middle of the night and this great thing occurred to me. It was April and I wasn’t going to be 50 until August. I had 17 free weeks. It was a death row reprieve! I thought I needed to do something really important with those 17 weeks. So having been drunk on book-love all my life I decided I was going to write a book.

BT: Mud Season touches on so many practical realities about living in Vermont. What would you say the biggest difference was in moving from St. Louis to a small town?

BT: Mud Season touches on so many practical realities about living in Vermont. What would you say the biggest difference was in moving from St. Louis to a small town?

ES: I think for me it was the complete lack of anonymity. In the city you don’t really have any privacy because you live right up close to people. But you have all the anonymity in the world. You can go to the coffee shop in your sweats and nobody knows you. But in the country it’s exactly the opposite. I can stand on my balcony in my long white gauzy nightgown any day of the week and nobody cares because nobody can see me. I have all the privacy in the world but none of the anonymity. If I say something outside of my front yard, an hour later half the town knows about it and before long the governor in Montpelier has heard the story. It just goes really fast.

The upside to that is you get this wonderful sense of community. If I drive my car off the road into a snow bank, somebody’s going to pull over and help me. As a result, we’re all nicer to each other. This last winter I was taking a friend to the airport while a storm was going on and a pine tree had fallen across the road. He was saying, “I’m going to miss my plane, what do we do about this?” And I said, “What we do is put on our gloves and we get out of the car and we move the tree.” We were one of about three cars, and those of us who were able were lifting branches off the road. Somebody else got a chainsaw. In about ten minutes we had the road cleared. We got back in the car and my hands had that piney smell all the way to the airport. The person in the car said, “I can’t even believe that happened.” But there are no people up here! If you want the tree moved, you’ve got to move the tree. Everyone pitches in. That lack of anonymity also translates to a wonderful sense of community.

BT: What shocked you the most about Vermont, and what, ultimately, was your favorite part?

ES: I’d never lived in a tiny little village. When you’ve only ever lived in cities, it’s really hard to understand that level of intimacy with your neighbors. It was really hard for me to get that it wasn’t just some house up the road, it was Lois. Her husband died 20 years ago, she needs help in the winter, and there’s no one here to give her help but me. I inherited Lois when I bought the house. That’s just how it is in Vermont. You inherit the neighbors and their needs and their peculiarities. That was shocking to me. I wouldn’t want to live any other way now, but it was shocking.

My favorite thing about moving to Vermont is the beauty. I’ve traveled around the world and I think that Vermont is one of the most beautiful places on the planet. It’s a beauty we can all share. If you’re in Cape Cod, there are only a very few people who have the gorgeous beach view. Those views are six million dollar views. In Vermont, everybody has a view. You come out of the grocery store and you have a view. We take for granted the natural beauty that surrounds us here. I was just out in my chicken house this morning – we have eight baby chicks – having coffee, and the mountains are around me, it’s a really sunny morning, my baby chicks are dozy and there’s the smell of pine and coffee. If you could bottle that and hand it out, it would calm everyone down.

BT: Humor is so important in your stories and often leads to very poignant memories and observations. What role do you think humor has in your books?

BT: Humor is so important in your stories and often leads to very poignant memories and observations. What role do you think humor has in your books?

ES: In my life, things are either wonderful or hideous but just waiting to turn into a funny story. And that’s really the truth of my whole life. For instance, the day that the woman drove away with the gas pump [at our country store], we looked at each other and said, “OK, this will eventually be a funny story.” And it was.

In Good Grief, there was this shocking thing happening in our lives. And yet there were still funny parts. While we were all sobbing, we couldn’t find Benjamin’s pants. I mean it was ridiculous. There is something wonderful about being able to laugh at the same time that you’re crying. It’s a way to get through it. It’s a way to see your way to the other side.

When I talk about this with people there are all sorts of responses. Everybody processes [Good Grief] through their own frame of reference. If you are somebody who has lost a loved one and you found it impossible to leave that painful state, then the humor might seem disrespectful to you. I’ve been surprised by that a little bit. That’s just not how we process the world around here. We process through joy and humor and I think we honor the people we love who have died by living. So for me the book was a tribute to Steve. A very loving way of paying tribute to him.

BT: While Mud Season is a fish-out-of-water story, Good Grief feels more personal in the way it deals with your family dynamics and events like Eli’s illness and Steve’s death. What do you see as the difference between the two memoirs, and how did your experience differ when writing them?

ES: Good Grief, in a sense, wrote itself. I wrote it all in one piece. Mud Season I wrote in a much more disjointed way and then tried to order it. It was more of a construction project than a writing project. Good Grief I wrote beginning to end; it was more of a traditional writing project. It was also very fresh. Mud Season had happened several years before – I sold the store in 2007 and wrote the book in 2012. Everything was still very new when I sat down to write Good Grief. It was a much easier process and I could see where I was going from the beginning.

BT: Do you plan on writing any more small town Vermont stories? And if so, do you have anything in the works?

ES: I’m in the middle of the third one. It’s about the marrying years of our young adult children, and really about marriage in general. It’s called, Wear Beige and Keep Your Mouth Shut. [Laughs] That’s the working title, anyway.

Buy this Book!

Amazon