When we were little kids, if we were lucky, someone would put us on their laps and say the magic words: once upon a time. The walls would fall away, time would vanish, and we’d be transported to a new world.

But I think we were also being introduced to the structure of a story. There’d be the character you cared about — a warrior princess, a despotic king, a rabbit who could talk — with a high- stakes problem that needed to be solved. There would be the journey, and the obstacles, and the decisions, and in the end, and everyone would live happily ever after.

We learned, as kids, to anticipate the rhythm of storytelling. Beginning middle end. The flow of a story. The expected architecture.

Later, when we tried to write the stories ourselves, we were told, as my favorite high school English teacher used to warn — you can’t successfully break the rules unless you know the rules. So we, learning the ropes, followed them to the letter.

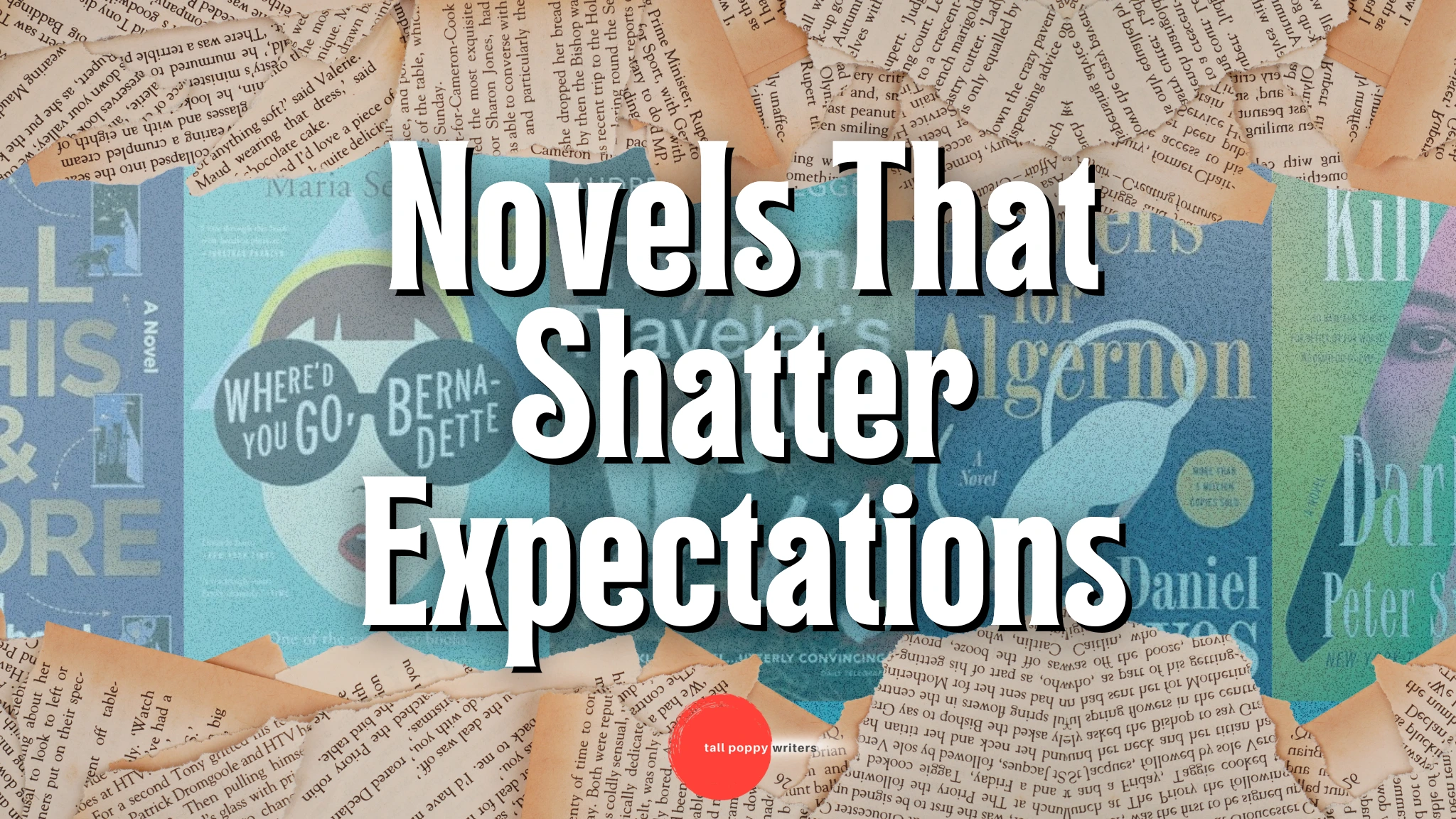

And then we figured out how to break them. We also learned to love the roller-coaster experience of reading books by other rule-breaking authors. Authors who supremely understand the beginning-middle-end necessity of a story, and then toss the whole thing in the air and let the pieces come down in a different order.

For instance — why should a story be chronological? Remember The Time Traveler’s Wife (2004) by Audrey Niffenegger? The timeline of that, as shattered as a broken mirror, rearranged our brains as well.

Why should a story be told in standard exposition? Daniel Keyes’ short story Flowers for Algernon (1966) told the tale through diary entries. Charlie, a man with an IQ of 68, is given experimental intelligence-enhancing surgery and his personal ‘progress reports’ — which begin with heartbreaking misspellings and construction and then evolve into brilliance — show us, gaspingly, what happens to him.

Why should a novel be all in one piece? Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night A Traveler (1979) used a series of mysterious and mystical short stories the morph into a novel. Even the chapter titles read from first to last work as a story of their own. This was one of the first books that made me think of how the form can inform the function.

Why should a novel be all one style? Maria Semple’s Where’d You Go, Bernadette (2012) wowed us with emails, letters, FBI documents, correspondence with a psychiatrist, even an emergency room bill. And put together in such a brilliant way that we deeply understand the story of Bernadette’s life.

And right now there’s a whole crop of brilliantly structured novels — where an already compelling story is amped up and steered through the twisted imaginations of brave and brilliant authors to present stories in a unique way. Our reader brains must deconstruct them as we read — adding another layer of fun as we discover the truth.

Janice Hallett blew me away with her brilliant The Appeal — one of the cleverest uses of documents I’ve ever seen. Emails, letters, playbills, even sticky notes — with the reader tasked to figure out what happened along with two engaging legal clerks. Her newest, The Examiner, is another imaginative and entertaining creation, a compendium of reports, texts, calendars, and message board — and again, dares the reader to solve the crime.

Cara Hunter’s Murder In The Family is a murder mystery come to life — cleverly and carefully written as the teleplay of a true-crime documentary. The reader gets to examine medical records and court records and police reports and photographs and documents and, essentially, becomes the detective in the story. It’s mind-bendingly immersive.

And hooray for Gillian McAllister, whose life-changing Wrong Place Wrong Time takes place on the day of the murder, and then progresses, backward, as a baffled and grieving mother tries to discover why her son became a murderer. What makes this book different is that it is not flashbacks, but a complete time shift, as the main character gets to regain her knowledge of the present while re-experiencing her own past. I will confess that when I started reading this, my writer-brain said, “she is never going to be able to pull this off.” I was totally wrong. It’s brilliant.

And proving the glorious truth that even an idea that might be described the same way can emerge as completely different, the brilliant Peter Swanson’s new Kill Your Darlings starts with a murder, too. And then tells us the story backward. How Swanson manages this absolute tour de force is completely ingenious, because what is revealed as the reader goes back in time wholly informs what we already know, and shows us how wrong we were about everything.

Why should a character be just one person? Tall Poppy Lisa Williamson Rosenberg’s unsettling Mirror Me has two narrators: one who lives within the psyche of the other. And a good chunk of the narrative puts the reader deep into therapy sessions — but exactly whose memory is being explored?

Carter Wilson gives us the riveting Tell Me What You Did, where the transcripts of a podcast terrifyingly duel with what we know is real life, and show us how deeply destructive and manipulative a live broadcast can be. Is the podcaster the cat or the mouse? Wilson also provides us with QR codes — so cool! — where we can see the podcaster in action, and get a view of the “evidence” in the story. Talk about interactive.

Well, okay, let’s talk about interactive. Peng Shepherd’s All This And More allows the reader to choose what happens next: click here if they get divorced, click here if they don’t. Go to this page if you think she lives, or to this page if you think she dies. You could read it again and again, and get a different story each time. I would adore to hear how she got this to work — but I know as a reader it does.

It’s difficult enough to write a book as we all know. But these authors are brave enough — and respectful enough of their fans’ reading skills — to raise the bar on their own imaginations. And grateful readers not only get the joy of solving the puzzle of the plot, they also get the fun of solving the puzzle of the book itself.