If you asked me today, and if you’d asked me two years ago, I’d tell you I’m very fond of my house. It’s nothing special. It’s a townhouse surrounded by other townhouses that look just like it, forming a semicircle of beige brick at the end of a street. There’s no garden, because when I bought it didn’t want something to look after—something that I would inevitably fail, by not watering it or not adjusting the shade or fucking up in some other way, and then feel guilty over.

It’s not small and it’s not large. It has a fairytale just-rightness.

For nearly a year of my life, beginning on my birthday in December of 2023, I despised it.

***

Houses in fairy tales aren’t usually there for your protection.

The really iconic ones all belong to the villains. My favourite is Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut, because it has the added menace of being able to chase you down. But there’s also the witch’s gingerbread house, which exists to be a trap for children. Or Rapunzel’s tower, which exists to be a prison.

The heroes and heroines of these fairy tales tend to interact with houses on a level of conflict and menace. The memorable ones don’t exist to provide refuge, or to be owned. Entering the real estate market is not high on the priorities list for your average orphaned goose-girl or fairy-cursed prince.

And there’s another genre full of excellently menacing houses: the Gothic. Here, things become a tad gendered. The Gothic is a genre about the relationship between A Girl (ingenue, often) and A House (large and foreboding, always). The house holds dark secrets relating to the past. The girl comes to the house. There might be a man there. I mean, probably there is. He’s all tortured and charismatic. He and the house are enmeshed in a tangle of pain and historical sins which the heroine must discover and disentangle, and thereby either escape the house-man dyad or transform it.

We all know the story. Plenty of fairy tales also contain it.

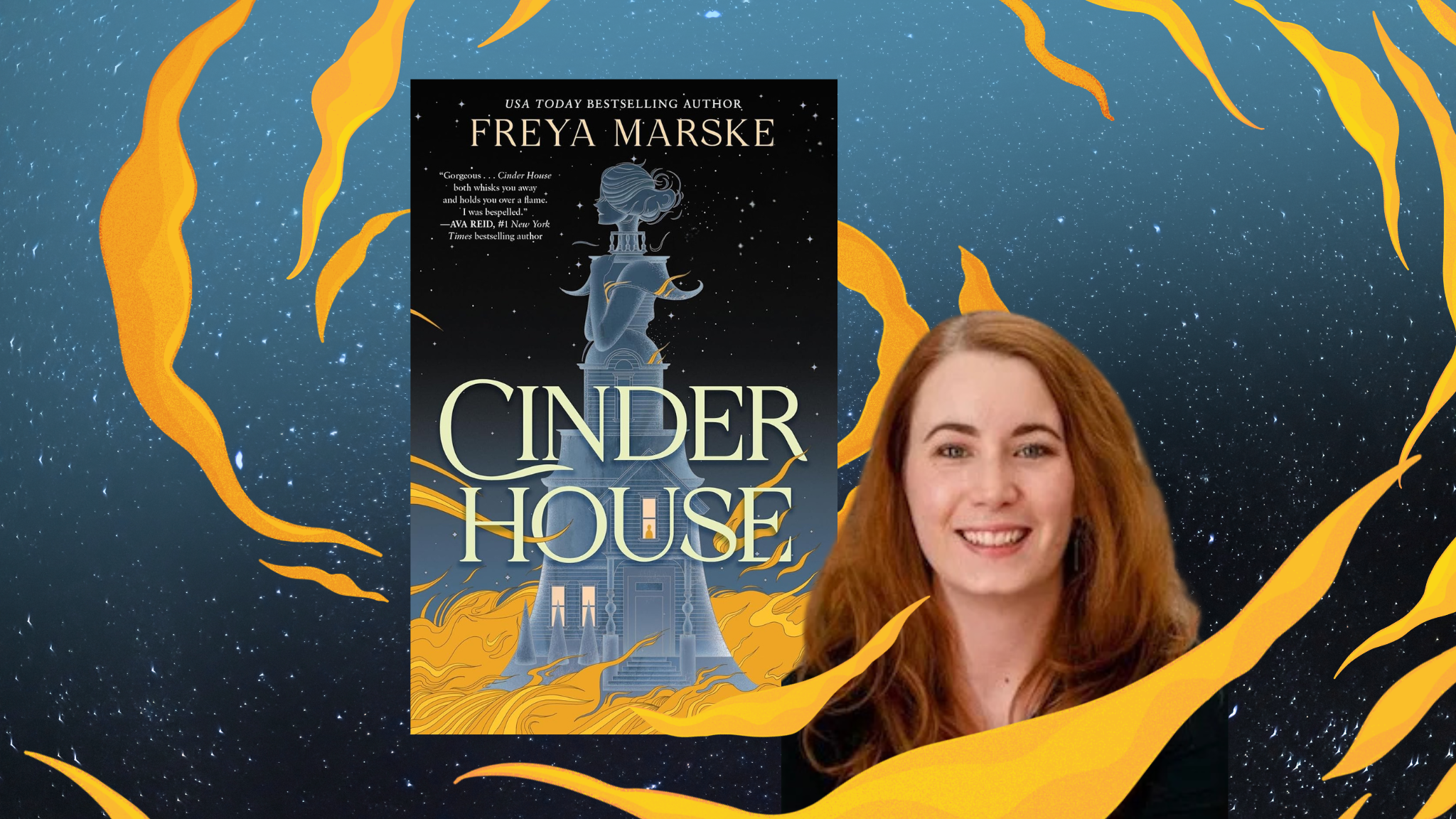

The origin story of my recent novella also involves a house.

And it involves the website formerly known as Twitter. Which, as we’ll be creakily telling our grandchildren, was once actually fun to be on for writers and readers alike.

One day something appeared on my feed: a writing prompt with a photo of a darkly brooding house. Write the first sentence(s) of a book that has this picture as its cover.

Something sparked pleasingly in my brain.

I posted: Ella’s father died of the poison in their tea. Ella drank less and so might have lived, and never turned ghost at all, if the house hadn’t shrieked for its master’s murder in the moment she stood, dizzied and weak, at the top of the stairs.

The iconography of the Cinderella story is mostly that of objects, transforming. Pumpkin to carriage. Rags to ballgown. Servant to princess. Cinderella’s house is never that interesting. It is, we assume, her childhood home, within which she transforms abruptly from beloved daughter to maid-of-all-work. Though if there’s anyone who knows a house inside and out, it’s probably the person whose job it is to keep the whole thing clean.

I picked up this ghost-Cinderella idea and put it away on my mental shelf. That’ll keep for later, I thought. I have other books to be writing.

***

In the second half of 2023 I was a fit, cheerful thirty-something-year-old who ice-skated for four hours a week and had three jobs including ‘writer of books’.

Despite working in healthcare over the scariest times of the pandemic, I’d never caught COVID. It felt like I’d been dodging an evil fairy-flung curse that had been doing its best to track me down.

I was writing a novel that I’d been planning for a while: a fantasy murder mystery, set at a magical medical school. Since the initial planning process, it had also become—I can’t imagine why—a book about working in healthcare in the wake of a paradigm-shifting pandemic.

In mid-November I did a US book tour. Then, tired and glowing and glutted with experiences, I flew back to Australia. In the fortnight that followed I skated in the local ice rink gala, plunged back into my non-writing jobs, and celebrated my birthday with friends at home.

The morning after that party, I woke up feeling sluggish and sore and unwell. I did a COVID test.

Curses have a way of finding you in the end.

***

What happened next feels tedious to tell but was, believe me, a thousand times more tedious to experience.

I was acutely sick for two weeks. I got a bit better. Then I got worse. My muscles ached all the time. I developed profound postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which has the menacingly whimsical acronym of POTS; standing up for more than a minute or so sent my heart racing, until I felt dizzy and awful and weak.

I couldn’t skate. I love skating.

The precious muscles of my butt and legs shrivelled up and vanished with a speed that felt genuinely insulting. My cardiovascular endurance vanished even more completely. I had been a light-wheeled filigree carriage and now I was a fucking pumpkin.

I didn’t want to eat anything. I love food. I love food even more than skating. That malevolent curse-flinging fairy was going to get it in the guts when I found her, for ruining the most beloved things that my body could do.

The illness changed my relationship with my body profoundly; and it changed my relationship with my house. I barely left the place. I grew to hate every single room of it.

I hated the bedroom where I would lie at night, unable to sleep, because I had done nothing all day and my aching body and frustrated brain informed me that we simply weren’t tired enough. I hated the living room and the blue couch where I would set up camp every morning, ready for another day of doing fuck-all. I hated my study, where sat a computer I wasn’t writing on and a yoga mat I wasn’t using. I hated the kitchen sink, where standing to wash a few dishes left me feeling light-headed and nauseated; in fact I hated the whole kitchen. I couldn’t chop a carrot or grate some cheese without my arms complaining from the effort. If my house had yellow wallpaper I’m sure I’d have started finding coded messages and evil spirits within it.

I detested the stairs. I suddenly dreaded every trip up and down, because it was a reminder of how much my thighs ached and how weak I felt.

It was the middle of summer, and very hot, which did not help my symptoms in the slightest. In a small carved-out exception to my consuming hatred, I was passionately fond of my air conditioning. I lived for that point in the evening when it cooled down enough outside that I could tolerate leaving the house and walking very, very slowly up and down the street. For two minutes. Maybe five. Maybe six or seven, on good days.

Other people have written books about chronic disease and how it leaves one feeling trapped. Suzanna Clarke’s incredible Piranesi is about a House that’s enormous and explorable but which you cannot leave, the main character’s existence both infinitely large and infinitely small.

I was lucky in one aspect of my Long COVID: the brain fog was minimal. I could concentrate enough to watch TV shows and read books. I could scrape together some creative juice, even if the juicing was a grim and active verb.

But every time I opened the draft of my novel about working as a doctor in the wake of a plague, I felt profoundly disconnected from it. I had moved categories. I wasn’t working as a doctor; I hadn’t worked in weeks, months. I was a patient of the plague. It was the wrong perspective for that story.

Still. I was sick of my ceiling and sick of myself and wanted to write something.

I reached up and took the ghost-Cinderella idea off the shelf.

Perfect. Escapism! Nothing to do with my current shitty life at all!

I didn’t realise at first how much what I was experiencing would shape the book. In fact, it was only midway through the writing process that I looked up and said “Oh…this is a book about my Long COVID.”

The basic concept was: what if there were a Gothic where the ingenue and the house were the same character? If the secret-driven intertwining was of heroine and house?

It’s a story about a girl who becomes a ghost on the very first page, and then spends a large part of the book trapped in her childhood home. Ella-the-ghost has no body and can only feel emotions with physical parts of the house. Chimneys. Wallpaper. Hearth. The staircase, which is where she died. She spends her days smouldering with anger for the loss of the life she’d always assumed would be hers, and constantly searching for ways to expand her smallness.

It does seem glaringly obvious, doesn’t it? I was writing about existence as something trapped, and also about existence as a house—

—because there’s something else that was going on during all of this.

****

Two days before I tested positive for COVID, I fell pregnant.

I didn’t know for sure that I was pregnant at the time. The two weeks of fevers and acute illness, the two weeks where I still expected that it would only be two weeks of illness, were also the two weeks of waiting for a blood test to tell me for sure. Normally I’d have been distracted by the rest of my busy life, but nope: I was stuck in the house, feeling like shit, staring at the ceiling, hoping—and also, secretly, guiltily, aghast at myself, dreading.

I’d been trying for a while. Another tedious story. Not one I’m going to tell here. But lying on the couch, hurting like someone had put me through a laundry-mangle and then transmuted my major muscle groups into lead, it did feel as though I’d found myself with a malevolent fairy bargain of getting exactly what I’d wished for—at the worst possible time.

Now I was not just in a house; I was a house. I was home to a cluster of cells who might one day be a person who was of-me and not-me. And as the weeks dragged on and I remained sick and also remained pregnant, I was absolutely terrified that I was not being a good house, but a toxic prison.

As a trained medical professional, I did my panic-searching on PubMed instead of the wider internet. (Well, at first. Let’s not pretend it didn’t metastasise.) I searched frantically for studies about the impact of catching COVID in the early first trimester, when all the important stuff like the nervous system was forming. I took my medical expertise and used it to doom-spiral expertly at the ceiling, all through the long nights of being not tired enough to sleep.

And I’d thought the guilt of letting a plant wither in a pot in the courtyard was bad. This was pure, highest-grade, artisanally hand-crafted guilt. What if I was failing her already? Hurting her already? What if I was the evil fairy, cursing her in her cradle at the start of her life?

It was extremely hard not to catastrophise. For one thing, being pregnant can suck even before you sprinkle COVID into the mix—for me, it felt like the two conditions were pulling together to make every symptom worse. The POTS came with nausea, and so did the first trimester; trying to wash those dishes left me retching helplessly over the sink. The fatigue of early pregnancy mingled seamlessly with the fatigue of the illness. And because I was pregnant I couldn’t take anti-inflammatories for the muscle aches.

Being pregnant was something else my body could do, which had never been asked to do before, and now had to do it when all it wanted was to collapse into a pile of grey ash.

As time went on, the guilt merrily clasped hands with the catastrophising, and whispered about all the things I might yet have to be guilty about in the future if I didn’t get better. I’d gone open-eyed into parenthood as that fit, working thirty-something-year-old, thinking I was prepared for the toll of pregnancy and the sleepless nights and the profound shift in my life.

There are still months to go, people said. You’ll probably get better.

And I said: Okay, well, a lot of Long COVID patients don’t.

It didn’t feel like catastrophising; it felt like realism. I’d read stories and studies. I knew exactly how bad it could get.

What if I didn’t get better? What if I couldn’t go back to work? What if I could still barely get myself up my stairs and then I had to get myself-plus-a-baby up them? What if time passed and I had an active toddler and I couldn’t even take her for a ten-minute walk? What if she brought COVID home from childcare, I caught it again, and deteriorated further? What if?

At this point I reminded myself firmly about the many extremely capable and loving disabled parents out there in the world. I read some essays and watched some YouTube videos and scrolled through some smart and funny social media feeds. That helped a lot.

I held on to gratitude. I had a wonderful supportive family and network of friends, who’d do my groceries for me, and mail me gifts, and come hang out with me on the couch for an hour, and reply to my mopey melodramatic messages. I could take leave from work and I had enough savings to do this without hesitation. A friend who’d gone through a similar thing recommended an exercise physiologist who did telehealth consults and was very sensible about Not Pushing Things.

Summer cooled. The year rolled into autumn.

I kept writing Ella’s story.

***

My appetite came back somewhere in the second trimester.

Well, I say appetite. All I wanted to eat was little pastry treats. Two Parisian friends in a group chat, distant and wonderful fairy godmothers, christened the baby Princess Macaron. I was eating a lot of macarons. And chocolate croissants. And Portuguese custard tarts. And hot cross buns. If I didn’t turn into a gingerbread house it wasn’t through lack of trying.

Thankfully, wondrously, things improved.

It was very slow. The POTS stuck around. The aches fluctuated. My energy improved as if someone were standing over me with a pipette, dripping it into me with a miserly frown on their face: Not too much! Can’t let her start hoping she can do anything!

I kept writing the book. The amount of hope I allowed my heroine as the draft progressed expanded and contracted along with my own. I knew it wouldn’t end simply, wouldn’t end in resurrection. It was about finding a path toward a new version of happiness.

By the middle of the third trimester I was going for longer walks. Princess Macaron looked fine on ultrasounds. I began to feel less like a poisonous prison and more like a prickly, sleepy castle, guarding the princess for as long as she needed to sleep before she emerged.

I went back to work on a schedule of not-very-many hours a week. I surprised all my patients with my belly and then scared them all into wearing masks on aeroplanes and getting their COVID boosters. Nothing like being a cautionary tale with a moral stamped on your forehead. Don’t stray from the path in the woods! Don’t treat beggar-women badly! Wear a fucking mask!

***

Not long before I was due to give birth, I finished writing the book. It was a fraction too long; all my drafts are. I whined and complained and then sat down and edited ruthlessly, trimming the toes, ignoring the pain and the blood, until it fit. It was a novella.

There was the usual publishing email chain where my original title was also ruthlessly chopped off and some better-fitting ones were brainstormed.

What we landed on was Cinder House. Of course the house had to be in the name. Of course, of course. The house was the book was the heroine was the house.

***

Nine months after I caught COVID my daughter violently left the house that was me and joined me in the house I couldn’t hate any longer, because now it was ours. It was like being slammed into a brick wall of joy. It was love like a blazing hearth.

And now it’s a year after that, I’m ice skating again and revising the magical medical school novel—and she, gremlin princess and best beloved artefact of the worst year of my life, has recently learned to walk. Soon, one assumes, she’ll be finding worlds in wardrobes and stumbling across fairies. If they offer her food, we’re doomed; she’ll put anything in her mouth.

Some people don’t get better. I got better. I don’t know why. I didn’t make a terrible bargain or go questing for a fabled cure. I made a lot of wishes: desperate, heartfelt ones. But I can’t put it down to anything except luck and, I suspect, the privilege of rest.

There are still times when my energy crashes and my upper arms inform me they’re going to be lead again, just for a bit, for old times’ sake. I still have a mild dynamic disability. It’s not the body I had and never will be. But better. Yes.

Life looks a thousand times more wonderful than I’d feared, and still nothing like I’d imagined.

Cinder House is a book about that. I dedicated it to my daughter.