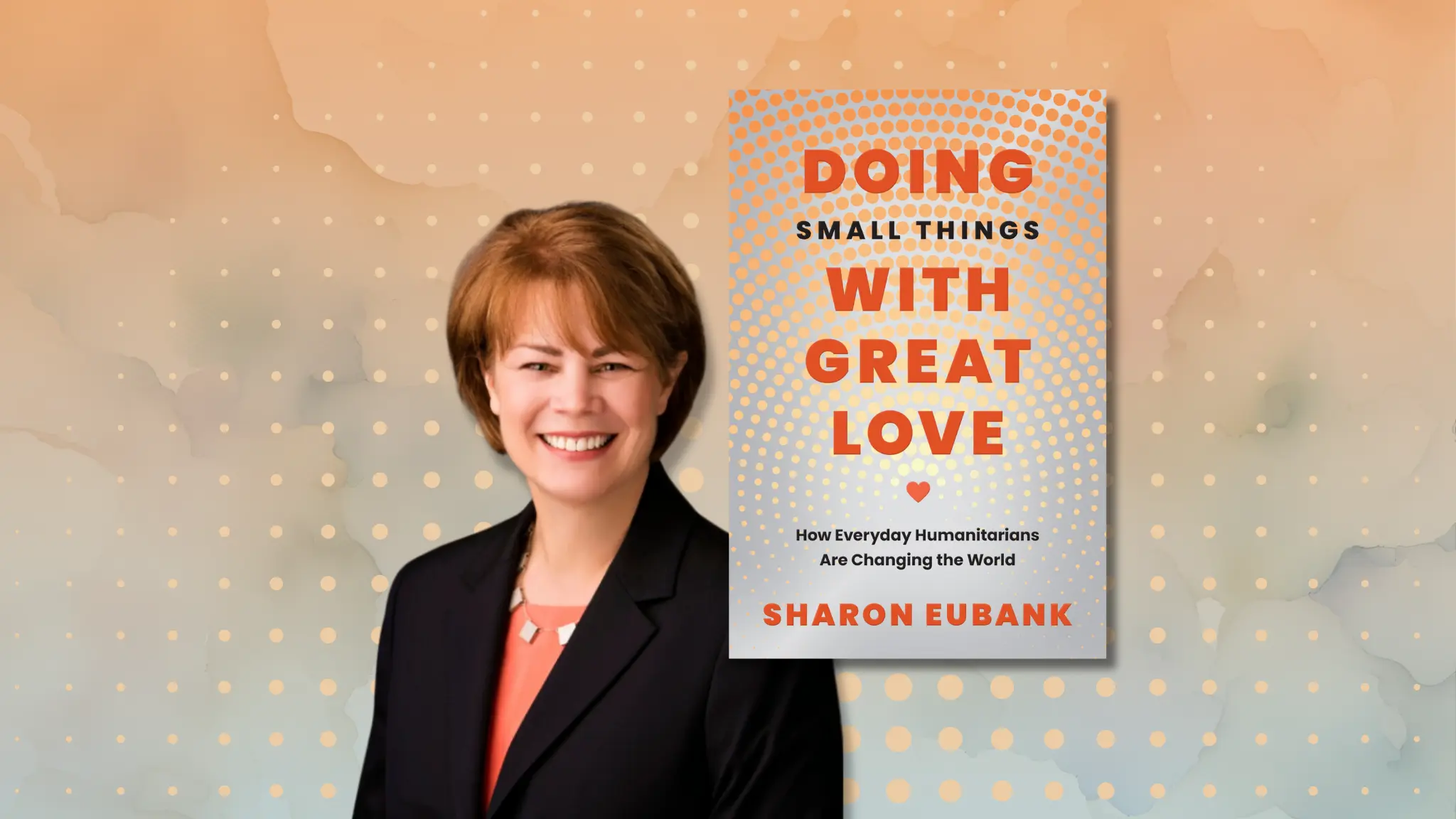

Doing Small Things with Great Love: How Everyday Humanitarians are Changing the World invites us to look closer to home for solutions rooted in shared humanity.

In this Q&A, author Sharon Eubank explores what it really means to work for the common good and why the most meaningful change often begins right where we live.

You note in the forward to the book that every culture has some version of what is sometimes called the Golden Rule. Why was that important to include?

The common presence of some version of the Golden Rule in dozens of traditions is special to me because it represents common ground. The thread of civil good runs through treating others as we ourselves would want to be treated. Human beings have been striving toward that ideal for millennia. It is one of the great civilizing principles of humanity — a unifying thread through almost every faith tradition and philosophy.

Human brains are built for judgment. We are constantly assessing: Is this a threat or a friend? Are they like me or are they not? With that basic function of our brains, we can’t help but categorize individuals around us by the way they vote, their dress or physical appearance, the ways they worship, their education or background, the sports team they cheer for. We use a hilarious number of measuring sticks to sum people up into neat little boxes. But the truth is, not one of us is a neat little box. We constantly surprise each other with our variety and contradictions. The categories we use to judge aren’t reliable and are constantly shifting. So, we need a different measuring stick. Perhaps treating others the way we ourselves want to be treated has proven its worth across the timeline of history.

The book includes 92 stories, and I was specifically trying to reveal the strong, consistent societal forces that are weaving us together rather than tearing apart our social fabric which appears in so much of the modern narrative. The Golden Rule seemed to be a capstone for those 92 examples.

One of the ideas of the book that surprised me was chapter 2 which is called You Are Most Powerful Where You Live. Are you implying that global humanitarian and development work isn’t effective?

I hope I’m not implying that, because I have spent a long career working in humanitarian and development sectors, but I was trying to share a core realization that shifted everything for me. I was in the beautiful country of Sri Lanka shortly after the massive Southeast Asia tsunami that happened on Christmas Day in 2004.

Story of Shanthe and the Train to Galle

Help from the outside is never going to be as powerful as help from within the community itself. They speak the language, they know the culture and history, they understand the cues and dynamics going on, they permanently stay. Those aspects are so much more powerful than money or outside resources—even if those are important. Funding doesn’t create permanent change. Change comes from the choices and wills of the people who live in that place. So, we are all powerful. And we are most powerful where we live.

Do you think our global problems are getting worse? With all the humanitarian efforts, have we made any progress over the last 100 years?

It’s true that we have much greater access to a variety of news from many sources. Rather than reading a hometown newspaper a couple of times a week or listening to 30 minutes of the evening news, the news cycle is now constant, delivered across all kinds of non-news channels, and it tends to hype and magnify certain stories.

It’s also true that the scale of weather and natural disasters seems to be intensifying. Droughts are longer, flooding is higher, hurricanes are more intense.

But I do want to point out that huge progress has been made in the last 200 years on big issues. Child mortality for example.

- For millennia until about 200 years ago, 50% of children died before age 15. Think of the impact on parents, siblings, families and communities. The leadership, innovation, dreams lost when 1 out of 2 children does not survive to contribute their unique talents to the world.

- In 1950, the number had decreased to 25%. This happened because of advances in public health, clean water, accident prevention, education, and vaccines.

- In 2020, the global number stood at 4%. This dramatic decline arose from better agriculture and nutrition, the development of supply chains to rural areas, basic services of sanitation and clean water, advances in neonatal healthcare, new immunizations for things like malaria, the rise of the middle class and global attention on famines.

- In some wealthy countries like Iceland, Japan, and Norway, the child mortality is 0.4%—ten times lower than the global average. Somalia currently has the highest rate 14%.

- Globally, every year, around 6 million children under 15 die. That’s around 16,000 deaths every day, or 11 every minute.

- What these figures tell me is that much more progress is still possible. Child mortality is one of the world’s largest, preventable problems. We know what works and what to do. It’s a matter of doing it equitably for everyone.

So that is a long way of saying, the news often masks some of the enormous progress that has been made over the last 200 years and there is reason to be hopeful that we can do more.

Do you have a favorite part of the book?

The part of the book I enjoyed writing the most is toward the end. I had read an interview in the NY Times Magazine with Robert Putnam who wrote the book Bowling Alone in 2000. The book was about how bowling clubs and other things like that in society that bring people together were decreasing and how much we needed those socially bonding venues. In the 25 years since he wrote the book he wanted to give an update and his new main point was that whatever you choose to do, it has to be fun. All this high-minded talk about humanitarian, development, and collective good is fine, but in the end we do things because they are fun. I wrote about the activities we do simply because we enjoy them—things like cooking and eating, sports, music, and volunteerism.

I highlighted my old friend Gustavo Estrada who is that guy who just brings the fun to anything we did together. We all know somebody like that. They walk in, and the party starts. Gustavo held informal salsa tasting parties, he brought hot chocolate to meetings, he sold Guatemalan food to fund his neighborhood robotics club. He brought snowcones to employment classes. His medium was food and he used it like a master to make everybody happy. We ought to have more fun in our lives as we try to make things better. It has to be fun. Gustavo passed away from liver failure in 2022 so this was a tribute to my friend. That was my favorite part of the book to write.

Would you read a section that was particularly meaningful to you as you wrote the book?

I was on a long airplane trip and I watched a documentary in the airline’s movie section about the presidency of Jimmy Carter. I was a high school student during this time, but I don’t have any memory of this speech. I rewound and watched it three times.

Near the end of his presidency, President Carter realized that public frustration of inflation, high energy costs, and the Iran hostage crisis were going to prevent his reelection, so he scrapped a speech he was going to give and decided to address the nation on the topic that was high on his mind. His advisors told him not to do it, but he wasn’t worried about getting elected anymore, and he wanted to speak to the American people about the democracy we all share. Democratic society can’t function very long if only a small percentage of people are prospering. When people and institutions start grabbing for their own advantage at the expense of others, it poisons the idea of the common good. This is what President Carter wanted to speak about 50 years ago.

PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER

“We’ve always had a faith that the days of our children would be better than our own. Our people are losing that faith, not only in government itself but in the ability as citizens to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy….

“These changes did not happen overnight. They’ve come upon us gradually over the last generation, years that were filled with shocks and tragedy. We were sure that ours was a nation of the ballot, not the bullet, until the murders of John [F.] Kennedy, Robert [F.] Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. we were taught that our armies were always invincible and our causes were always just, only to suffer the agony of Vietnam. We respected the presidency as a place of honor until the shock of Watergate…. These wounds are still very deep. They have never been healed….

“We know the strength of America. We are strong. We can regain our unity. We can regain our confidence. We are the heirs of generations who survived threats much more powerful and awesome than those that challenge us now…. We are at a turning point in our history. There are two paths to choose. One is a path I’ve warned about tonight, the path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest. Down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom, the right to grasp for ourselves some advantage over others.

“All the traditions of our past, all the lessons of our heritage, all the promises of our future point to another path—the path of common purpose and the restoration of American values….

“In closing, let me say this: I will do my best, but I will not do it alone. Let your voice be heard. Whenever you have a chance, say something good about our country. With God’s help, and for the sake of our nation, it is time for us to join hands in America.

“We are all Americans together, and we must not forget that the common good is our common interest and our individual responsibility.”

I let that last phrase ring in my head. The common good is our common interest and our individual responsibility. I can live up to my individual responsibility and build on my personal privilege to find common ground with others. I can work shoulder to shoulder with them to restore faith, heal wounds, and build bridges. These are things I can do.

I can get involved in local issues. I can donate money where I have confidence that it will advance the work of trusted networks. I can advocate with my local and national government and raise my voice on behalf of those who cannot raise their voices. I can live my life with a gracious respect for others who are different from me. I can learn about current events and gather others to work on productive solutions. I can take the next generation with me as we learn together.

We can’t let self-interest or inertia stop us from working for the common good as we see it. The difficulties are real, but we have done much and can do much more to improve society and make it safer, healthier, more equitable, and more enjoyable. The power is in us.

What is it you hope people will do after reading the book?

I had a newspaper reporter pin me down recently and say: Give a clear assignment; tell people exactly and specifically what they can do to help. Otherwise, the lack of focus will lead to nothing at all. I appreciate the desire for a clear-cut call to action, but the issues we face are, at their core, hyper-local. What works in one setting will be disastrous in another. The reasons women don’t have access to prenatal vitamins in Knoxville, TN, are completely different than in San Juan, Puerto Rico. There is no one-size-fits-all assignment to address the issue.

But the book is full of aids to help people get started.

- I’ve focused on 12 transferrable principles: You are most powerful where you live, My solution to your problem will always be wrong, and local solutions for local problems. The principles act as a roadway to the destination of specific solutions, but people are going to have to walk the road themselves and find their own calls to action.

- Each chapter in the book has some questions at the end to think about or start a discussion. These are patterns of the kinds of questions anyone could ask to start understanding what the root problem is in San Juan vs Knoxville. The best solutions come out of the answers to questions—but humanitarian work is not always done that way.

- If you passionately want to make a difference, you will need to start talking to people, asking questions, listening deeply to what is being shared with you. There are 50 prompts at the back of the book to help someone get started. Things like: Cook with kids and let them make decisions about how to follow the recipe, or Read a book or article about an issue you don’t support to broaden your thought channels.

I hope readers of the book will start asking questions and listen deeply to the answers. I hope they will choose a local issue they really care about and get involved in a root solution. I hope they will describe their own experiences on the social sites called Small Things Great Love so it can be a marketplace of new ideas.

About Sharon Eubank:

Sharon Eubank was born in Redding, California, she is the oldest of Mark and Jean Eubank’s seven children. She served as a full-time missionary for the Church in the Finland Helsinki Mission and received a bachelor’s degree in English from Brigham Young University. After graduation, she taught English as a second language in Japan, worked as a legislative aide in the U.S. Senate and owned a retail education store in Provo, Utah.

Sister Eubank served on the Relief Society general board from 2009 to 2012, chairing the Relief Society presidency’s Public Affairs committee. She has also served in numerous ward (local congregation) and stake (diocese) leadership positions, most often as a teacher to men and women, youth and children in the Church’s Sunday School, Relief Society, Young Women and Primary organizations. She loves history, homemade pie and crossword puzzles. She has a strong testimony of the happiness that comes from following Christ.