Women had very little power in Victorian England. They couldn’t vote, they seldom had a voice, and they were even restricted in the books they were allowed to read. And yet, there were intrepid women who found quiet ways to resist. A bloom pressed into a bouquet, a powder stirred into a teacup, the gleam of a hat pin hidden in a brim, even a book slipped into their personal library, each a silent weapon.

The idea of Victorian floriography has always fascinated me — that romantic language of flowers used to share information, evoke affection, or even stir up a bit of trouble. For women whose voices were so often dismissed, these bouquets became a coded language. Foxglove could imply secrets, hawthorn meant hope, oak symbolized bravery — on and on, each flower carrying its own hidden message.

But when protection was necessary, and something sharper than a lady’s wit was required, she need look no further than her own hat. Nearly a foot long, the sharp pins that secured elaborate hats also doubled as ready-made rapiers. Not only did women use their hat pins as easily accessible weapons, but they even attended instructional courses on how to properly wield them. What began as fashion became a revolt, a symbol of survival slipped through the laws of propriety.

Then there were the poisons. Arsenic, laudanum, belladonna — these everyday substances were tucked into medicines, cosmetics and kitchen cupboards. Add to that foxglove, lily of the valley, oleander, all innocent little poisons blooming in genteel gardens. With them came a cultural unease, the possibility of what women might one day stir into their husbands’ soup. Poison became a whispered threat, an unsettling shadow in a teacup.

And perhaps the most subversive act of all was reading. Books offered women escape and imagination from a world that demanded their silence. Even more, books featuring heroines who resisted convention quietly challenged the strict boundaries drawn around them. Reading became a rebellion of the mind, a way to claim power, agency and possibility in secret.

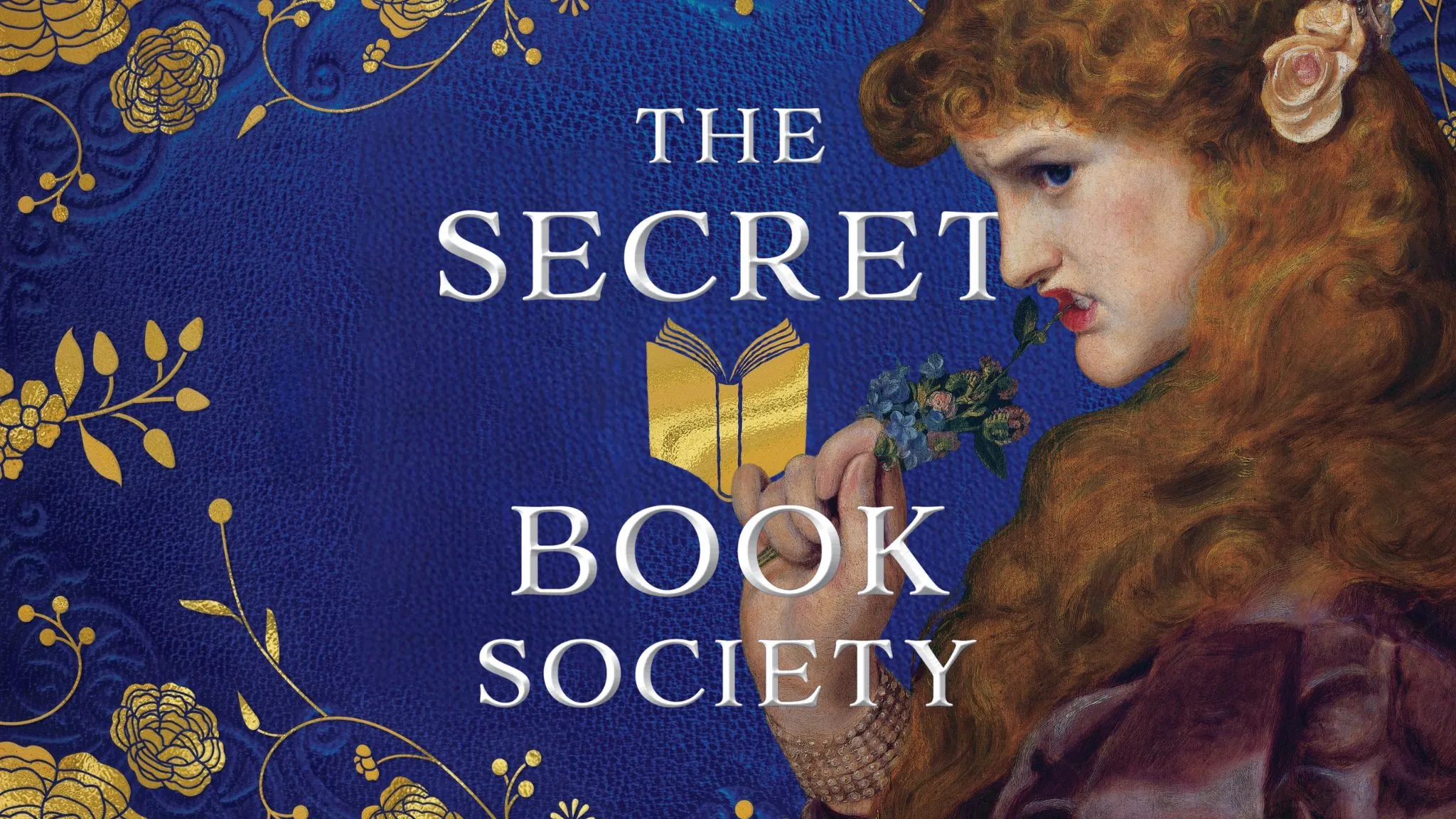

Floriography, hat pins, poisons and forbidden reading aren’t just footnotes in history — they’re the heartbeat of my new novel, The Secret Book Society. Set in Victorian London and hosted by the enigmatic Lady Duxbury, who is rumored to have killed her three husbands, the Secret Book Society hides behind tea and banal womanly gossip to mask secrets, resistance against oppression, forbidden learning through books, and rising empowerment.

Floriography, hat pins, poisons and forbidden reading aren’t just footnotes in history — they’re the heartbeat of my new novel, The Secret Book Society. Set in Victorian London and hosted by the enigmatic Lady Duxbury, who is rumored to have killed her three husbands, the Secret Book Society hides behind tea and banal womanly gossip to mask secrets, resistance against oppression, forbidden learning through books, and rising empowerment.

In their world, a flower is never just a flower. A rumor of poison lingers in the air. A hat pin glints with possibility. And every page turned is an act of defiance.

Because this isn’t only history — it’s a reminder. Even in the most restrictive times, women found ways to carve out power, to claim space, to connect and support one another. And now, readers are invited to join that circle of resistance, to slip into a world where every bloom hides a secret, every shadow hums with danger, and every story has the power to change a life.

Not all revolutions begin with a bang. Some start in a book club.