Until I was about 7 or 8 years old, I thought everyone heard “Friday” as a cluster of small purple circles and “Saturday” as a length of polished chrome pipe. I was shocked when my mom told me that was not the case. While she took it in stride, my description of these and other sensory overlaps, pretty much everyone else thought I was nuts. I learned to keep my intersecting sights, tastes, and sensations to myself. As an adult I discovered there was a name for what I had: “synesthesia,” a neuropsychological trait where the stimulation of one sense causes the automatic experience of another sense. The most common example is “grapheme” in which a person sees letters or numbers in specific colors. For example, someone might see all numeral 9s in a particular shade of dark blue or the letter A in lime green. Synesthesia is a genetically linked trait that affects 2 to 5 percent of the general population.

Serious scientific study of the phenomenon of synesthesia has gone in and out of fashion. It’s been considered everything from a complete figment of many imaginations to a legitimate subject of inquiry. At the moment the topic is undergoing a bit of revival.

The five books below include biographies of synesthetes and a neurologist’s research on the condition, written in terms a layman can easily understand. Even readers who have never given the topic a thought will likely be intrigued.

The Noisy Paintbox by Barb Rosenstock and Mary Grandpre

The children’s picture book The Noisy Paintbox by Barb Rosenstock and Mary Grandpre, about Vassily Kandinsky, provides an entry-level look at grapheme synesthesia from a visual artist’s point of view. It’s commonly believed that creatives are more likely to have synesthesia than others, although so far the data is inconclusive.

Perhaps creatives just talk more about the weird things they experience. When as a child Kandinsky stirred the paints in a box his parents had given him, the action released for him (and no one else in the room) sounds like an orchestra tuning, filling the space around him with musical tones and colors. The consistent presence of those overlapping sensations made it impossible for Kandinsky to tame his paint into the traditional landscape studies he was assigned, and forced him to abandon art for the law.

Years later, a performance of a Wagner opera set loose for Kandinsky such a powerful onslaught of shapes, color, and sounds that he was compelled to return to his studio and create the striking abstract paintings the world admires today.

Franz Liszt: Musician, Celebrity, Superstar by Oliver Hilmes

Oliver Hilmes’s biography Franz Liszt: Musician, Celebrity, Superstar, doesn’t restrict itself to the musician’s synesthesia, which was but a footnote to Liszt’s extraordinary music and life in any case. Contemporary accounts do have the great composer/pianist telling the orchestra, “Gentlemen, a little bluer, if you please!” and demanding that the orchestra not to go “so rose,” because the music was instead a “deep violet.”

Hilmes’s biography makes clear that seeing music in color would have been just part of Liszt’s creative legacy. As a performer, he was so charismatic that women fainted during his concerts. There was practically a queue to become one of his lovers. His piano playing astonished, and his compositions, acclaimed as they are, are nevertheless considered by some experts to be underappreciated.

The biography is a pleasurable page-turner for readers who aren’t looking for in-depth analysis of Liszt’s music. Instead, it’s a veritable who’s who of the mid-nineteenth century European artistic and aristocratic elite, and a fascinating study of one of the world’s first media-savvy superstars.

Surely You’re Joking Mr. Feynman: Adventures of a Curious Character by Richard Feynman

The brilliant, quirky, Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman was also a synesthete, once writing, “When I see equations, I see letters in colors — I don’t know why … I wonder what the hell it must look like to the students.” In his autobiography, Surely You’re Joking Mr. Feynman: Adventures of a Curious Character, the curious character tells so many other wild tales that seeing equations in color would hardly register. The title of the book is perfect. Feynman was not simply a curious character, but also a character with an insatiable curiosity who did not rest until he got to the bottom of absolutely everything. As Feynman put it, “I don’t know what’s the matter with people: they don’t learn by understanding; they learn by some other way — by rote, or something. Their knowledge is so fragile!”

Feynman’s knowledge was not fragile. He was as interested in human beings as he was the physics of the Manhattan Project or the cause of the space shuttle Challenger’s O-ring failure. A gifted raconteur, Feynman’s tales are intelligent and funny. I read the book sometimes wondering how many of these incidents happened exactly as he described them, but didn’t care if some of the details were exaggerated because his observations are profound and his stories are thoroughly entertaining.

Born on Blue Day by Daniel Tammet

For an exploration of the life of a “classic” savant with synesthesia, Born on Blue Day, Daniel Tammet’s autobiography, fills the bill. Tammet, one of the world’s fifty living autistic savants, can identify the day of the week for any date, and compute and memorize Pi to the 22,000th digit. His synesthesia means he perceives numbers as shapes, colors, textures, and motions.

Although he failed to find a comfortable way through the social milieus of school and the workplace, he nevertheless developed the capacity as an adult to form an intimate relationship and to relate to other people, especially outsiders, in part through his astonishing facility with languages. The book offers the reader a unique opportunity to spend time in a particular type of consciousness and comprehend the challenges Daniel and those like him face: while he might be able to learn Icelandic in a single week, taking a city bus requires practice and possibly even a human guide to get from Point A to Point B.

I finished this book with a much better understanding of autism and an admiration, even affection, for brave, intrepid Daniel.

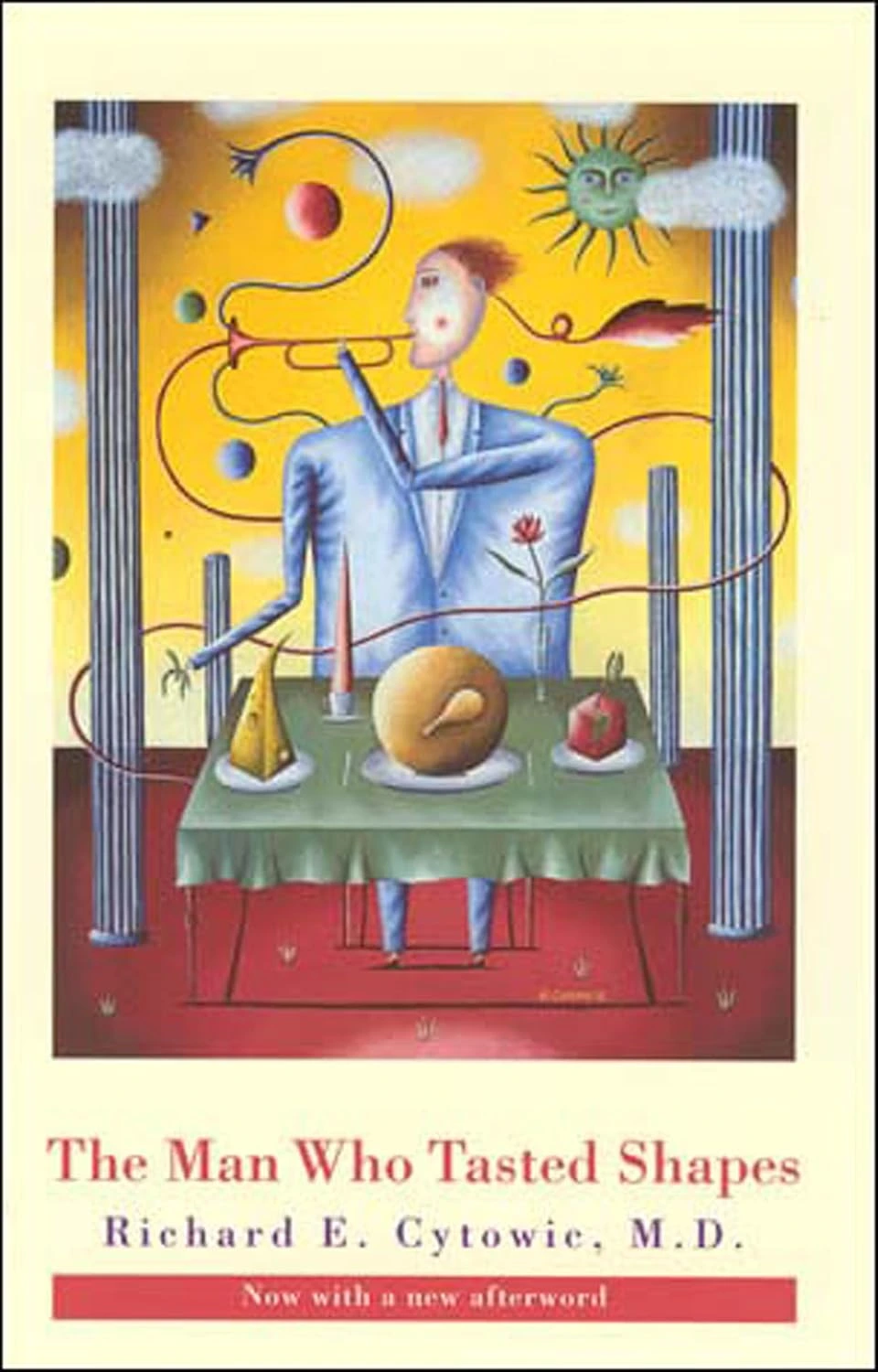

The Man Who Tasted Shapes by Richard E. Cytowie

Neurologist Richard E. Cytowie is among the world’s foremost researchers on synesthesia. His book, The Man Who Tasted Shapes, begins with an anecdote about Michael Watson, an acquaintance of Cytowie’s who perceived flavors as shapes. Michael inadvertently let it slip that a chicken he’d been roasting for a dinner party was a failure because it “did not have enough points” and therefore would be flavorless.

As Dr. Cytowie was already familiar with synesthesia, he immediately understood what Michael perceived and invited him to participate in the neurologist’s further work. The book is a compilation of the experiences of individuals who have the condition, the doctor’s research findings, and his ruminative essays on the future of brain science.

Unlike previous researchers who tended to limit their subjects to savants and those on the autistic spectrum, Dr. Cytowie includes everyday people and those who have milder versions of the condition. Also, unlike earlier studies, Dr. Cytowie’s recent research delves into the emotional and even spiritual aspects of synesthesia.

His afterword also notes that synesthesia tends to wane somewhat after childhood for most people, possibly due to reasons related to anatomy or differences in adult brain function. I wonder if choosing to ignore synesthesia’s distracting displays might also play a role?

Distracting or not, less frequent occurrences have been the case for me as an adult, much to my regret. Research seems to show, however, that meditation may increase synesthetic incidents. I hope so! With fingers crossed, I plan to find out.

Lit Garden is a monthly book recommendation column from Diane Parrish. You can view previous columns here.