In Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Buried Giant, an entire society has literally lost its ability to remember. One such couple has muted memories of having had a son, of having once loved one another. But those memories seem to become more and more opaque every day. In a moment of reflection, the man says to his wife, “I’m wondering if without our memories, there’s nothing for it but for our love to fade and die.” It’s a poignantly terrifying thought, don’t you think?

If you’ve ever read Ishiguro, you know that he writes about the fragile nature of memory in almost all of his novels. But he’s not the only one. Authors like Marcel Proust (In Search of Lost Time), Toni Morison (Beloved), and Margaret Atwood (The Blind Assassin) all explore how memory, especially traumatic memory, shapes identity.

And then you’ve got genre fiction. Think of all the amnesiac protagonists in noir and crime fiction (The Black Curtain by Cornell Woolrich, The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins, The Last Good Kiss by James Crumley, I Wake Up Screaming by Steve Fisher to name a few).

And what about all the plots centered around altered memory in science fiction (The Total Recall and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, Altered Carbon by Richard K. Morgan, The Maze Runner by James Dashner)? All of these novels seek to answer very serious questions: Are we still human if we have lost our capacity to remember? Does a soul exist without a past?

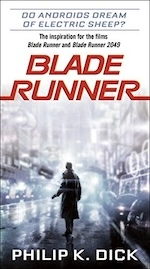

Exploring the beauty and pain of memory has always been a literary obsession for me, and never so much as in my latest novel, The Memory Ward. At the beginning of the novel, we learn that our protagonist, Hank, a 30-something-year-old postal carrier, has spent the last 10 years of his life living in a kind of ignorant bliss, wandering through the idyllic town of Bethlam, Nevada, delivering mail and greeting neighbors. Sure, he’s faintly curious as to some of the oddities in town.

Why, for example, do so many people seem to watch him from their kitchen windows? Why do so many people, in this safe and friendly town, carry concealed weapons? When a strange woman knocks on his window one night and warns him not to trust anybody, including his wife, he begins an investigation into the dark secrets of the town.

But this investigation morphs into an examination of himself and his memories — and perhaps his own sanity. Because while Hank has an acute memory — a form of hyperthymesia, he’s told — he begins obsessing that maybe his remembrances aren’t as real as he’s always assumed them to be. Each day he swims in vivid nostalgia, reliving the taste of kisses at the County Fair, remembering the smell of cinnamon rolls being baked, recalling the sound of leather as he played catch with his father.

But are these memories too vivid? Is it possible that those memories are false, that his entire identity is somebody else’s imagination? I hope The Memory Ward is entertaining. I hope it makes you ponder big questions. And if I’ve really done my job, maybe it will even have you questioning your own sanity and sense of reality. What more could you ask from a novel?