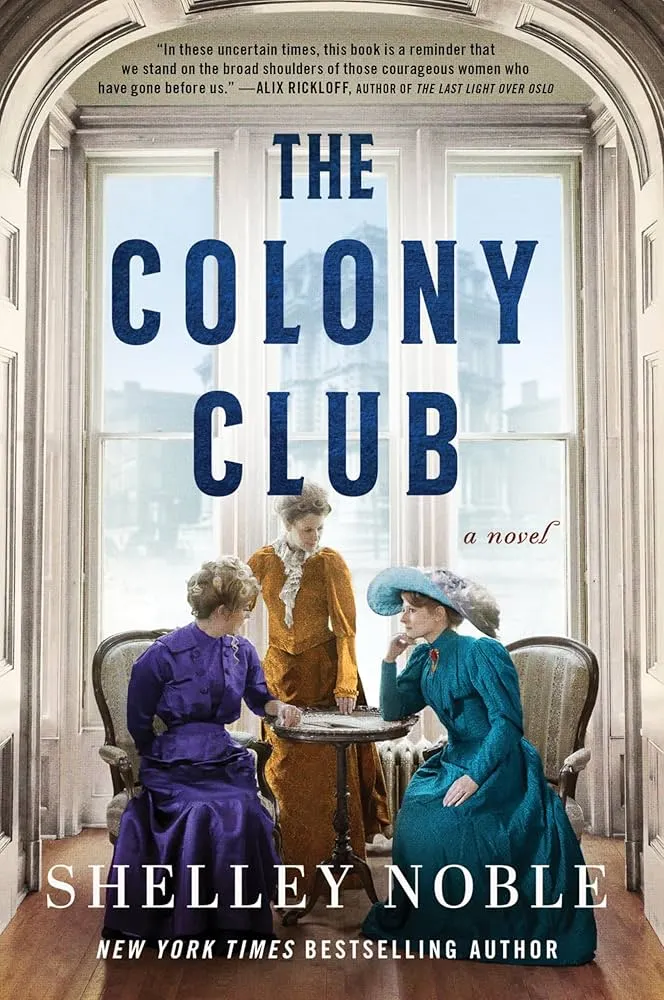

The Colony Club by Shelley Noble

The Colony Club is the epitome of what historical fiction should be, as the genre all too often misses the mark, riddled with anachronisms or carelessly blatant errors. Author Shelley Noble deftly balances clearly identified actual people, places and events with plausible vibrant fictional characters portrayed in a lively story that draws the reader in, holds their interest and tugs at the heartstrings.

This novel is a masterful work that fully captures the challenges, drama and excitement of the establishment of New York’s first ultra-exclusive, invitation-only membership-based women’s social club built during the Gilded Age by Stanford White. He was the most sought-after architect of the time, a member of the prominent Beaux-Arts firm McKim, Mead & White established in 1879.

Former Broadway actress, one of the city’s best-dressed women and society darling Elsie de Wolfe was given her first commission to design and fully decorate this elegant establishment with an unlimited budget. It launched an enormously successful and lengthy career in the relatively new profession of interior design.

The Colony Club is told from the points of view of three primary characters; the non-fictional Daisy Harriman and Elsie de Wolfe and the fictional aspiring architect Nora Bromley who is dynamic and central to the novel. The primary narrators are Daisy and Nora.

The Founding of The Colony Club

The story begins in April, 1963, with the original founding member of The Colony Club, 92-year-old Florence “Daisy” Jaffray Hurst Harriman, being interviewed by a young journalist about being the first recipient of John F. Kennedy’s Presidential Citation of Merit Award for Distinguished Service.

Born into wealth in 1870, the pretty, vivacious and highly intelligent Daisy was a leader from an early age and involved in the typical charitable and civic activities that befit the wife of successful financier J. Borden “Bordie” Harriman whom she married when she was nineteen. His first cousin was railroad tycoon Edward Harriman, whose son was politician and diplomat W. Averell Harriman.

Daisy was a committed suffragist, who attended speeches, wrote letters and led marches; a social reformer determined to improve food purity, working and living conditions for the disenfranchised poor and the implementation of child labor laws. She became a Wilsonian Democrat and shortly after he became President was appointed by him as a member of the newly founded Congressional Commission on Industrial Relations. She ramped up her participation in politics and charitable activities after her beloved husband Bordie died in late 1914. She converted her grand Mount Kisco summer home in Westchester County, NY into a tuberculosis sanatorium.

Mrs. Harriman participated in the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference, and was an advocate for the League of Nations before becoming the first president of the Woman’s National Democratic Club founded in 1922. She was appointed by President FDR as United States Minister to Norway from July 1, 1937 until April 22, 1940 when Nazi Germany invaded Norway. Daisy Harriman was at the center of too many world events to detail here and not even vaguely interested in reviewing these achievements with the awed woman set to profile her.

Led By Female Movers and Shakers

Instead of an in-depth autobiographical interview, the journalist is treated to a look back at the origins of The Colony Club. It began when the youthful society matron Mrs. Borden Harriman was refused a room at the Waldorf Astoria. It was August 1902, their 5th Avenue home was being renovated and she needed to be in New York City for a few days during the height of summer season in Newport where her friends were entertaining.

When she attempted to book the reservation, her private secretary was told that the Waldorf “did not cater to unaccompanied ladies, no matter who they were.” It was just the impetus needed for Daisy to swiftly convene an organizational meeting of her powerful friends with the intention of building a women’s only club to equal their husbands’ urban bastions such as The Union Club, the oldest men’s club in existence in America since 1836, The Metropolitan Club and The Princeton Club.

J.P. Morgan’s three daughters, Mrs. John Jacob Astor, and Mrs. Payne Whitney and several members of the Vanderbilt Family were among her chums who helped raise the initial half million dollars. They were aided by the participation of pioneering theatrical and literary agent and Broadway producer Elisabeth “Bessie” Marbury, a member of a wealthy and socially prominent old New York family with distinguished 17th-century New England ancestors who also became an active founding member of the club. Bessie was Elsie de Wolfe’s partner in life for nearly 40 years until Bessie’s death in 1933.

Stanford White was then commissioned to design their first clubhouse, located at 120 Madison Avenue between East 30th and 31st Streets. Construction began in 1904. Not every woman in their social set participated due to their husbands’ objections or because they felt it unnecessary when they could entertain in their own homes. There was outside opposition as well once the project was underway from clergymen who viewed it as unseemly and temperance movement leaders who sought a pledge there would be no alcohol served.

These socially prominent and wealthy female movers and shakers responsible for the inception, planning, organization, financing and construction of this grand edifice rivaling the finest private men’s clubs succeeded despite various obstacles with the grand opening occurring in early 1907. In addition to providing overnight lodging, fine and casual dining, servant’s quarters, a concert and lecture hall, it also offered a gymnasium, swimming pool, mud and sulfur baths and a running track. It boasted of providing spacious pet kennels and a “stranger’s room” where male guests were received. The initiation fee for the original 500 members was $150 with annual dues of $100 which was on par with the most exclusive men’s clubs.

A Shocking Scandal and Immoral Behavior

One major setback occurred on June 26, 1906, a few months before the completion of construction when 52-year-old Stanford White was shot to death at close range in front of hundreds of witnesses while attending “Mamzelle Champagne” in the rooftop theater of the original Madison Square Garden which he had designed. It would become New York society’s “Scandal of the Century” when details of the case and trial were made public.

The age of consent was far younger than is currently legal and deemed acceptable today and this middle-aged man had a marked penchant for beautiful young girls whom he showered with gifts as part of his seduction. Among those lovelies was artist’s model Evelyn Nesbit, a chorus and “Floradora” girl and probably one of the Gibson girls who at age 16 was either seduced or ravaged before becoming his mistress for six months. White provided Evelyn and her mother with an allowance and pleasant living quarters while lavishing extravagant gifts of furs, designer clothing and fine jewelry to the girl.

Two years after their relationship ended on good terms and with her theatrical career on the wane, 19-year-old Evelyn married Pittsburgh multimillionaire Harry Kendall Thaw. He was insanely jealous and a brutal sadist who during his undergraduate years had been expelled and given three hours to leave Harvard University’s campus after accusations of “immoral practices”, additionally intimidating both faculty and fellow students. His inappropriate behaviors earned him the status of social pariah in New York and he was deeply envious of Stanford White’s sphere of influence.

According to press reports, murderer Henry Thaw stood over the body and declared “I killed him because he ruined my wife.” Almost immediately, the immensely popular architect’s luminous reputation was permanently besmirched. Although the brilliant, extravagant, charismatic architect was married, his wife and son lived in the family home on Gramercy Park or stayed at Box Hill, a White designed grand summer house, situated on sixty acres on the north shore of Long Island.

“Stanny” as friends and good clients called him maintained a separate Manhattan apartment. (The estate remains in the family. His son, architect Lawrence Grant White and his wife Laura Astor Chanler had produced eight children and 35 grandchildren.) Stanford White’s legacy of architecturally significant public buildings and homes became sadly overshadowed by his private life in the court of public opinion.

Thaw’s devoted mother spared no expense in “The Trial of the Century” defense of her darling son. While awaiting trial, the Millionaire prisoner was granted special privileges including permission to wear his own custom tailored clothing, meals delivered from Delmonico’s complete with wine, books and cigars and comfortable bedding complete with maid service.

Evelyn was apparently given a significant sum of money to enumerate in court the alleged abuses from Stanford White. Thaw was tried twice with the first ending in a mistrial and the second with a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity with a life sentence in a mental institution which was later overturned. He was then set free to pursue future questionable escapades which were routinely covered up through significant expenditures to injured parties. He remained a thorough-going reprobate until his death.

Fiction Blends With Real Accounts

The fictional gifted artist Nora Bromley’s role in The Colony Club centers on her training as an aspiring architect and subsequent employment as well as her relationship with her family and coworkers including a budding romance. She was first hired as a draughtsman by Stanford White and later assigned to work with Elsie de Wolfe on the technical aspects of interior design.

Nora, raised in Lower East Side tenements, was smart, talented and possessed a driving ambition and steely determination to design and build a hospital for tuberculosis patients, the disease that killed Jimmy, her brother and best friend. Using a small legacy from her late father and money earned from tutoring, she was about to graduate from the New York School of Applied Design when the novel begins. Her senior project, a modern hospital with rooms filled with light and air rendered in impressively detailed watercolors, won first prize in the student competition judged by a panel that included the eminent architect Stanford White.

The $50 cash prize also came with an opportunity to interview for a junior staff position with the McKim, Mead & White firm. As the only female draughtsman in a firm that was all male except for the clerical staff, Nora was subjected to covert and even open hostility that sometimes escalated to petty theft of her drafting and art materials and outright sabotage. She refrained from complaining to the project manager, working long hours on difficult assignments with short deadlines. Her detailed watercolors of elevations as well as technical layouts required by the civil engineering team earned her admiration.

However, she resented being assigned as technical advisor and sketch artist for Elsie de Wolfe who had great visions, fabulous taste and tremendous style but no understanding of load-bearing walls, electrical conduits and plumbing when designing the interiors. She often left the country on buying sprees leaving Nora to coordinate with the construction crew. Ultimately the results of their joint labors was a dazzling departure from dark, heavy wooden furnishing as the rooms were fitted with light chintz fabric prints and delicate chandeliers and light fixtures that harmonized with the antiques, furnishings and art collected during her two year shopping spree in top European markets.

Nora Bromley feared her career would crash to an end after Stanford White’s murder when a jealous, spiteful male co-worker deliberately lied to the press that she was one of White’s “young protégées”. Her roommates and landlady evicted her from her rooming house and her older sister banned her from her home. Fortunately, new friends came to her rescue.

Social Change and Universal Suffrage

Daisy Harriman, Elsie de Wolfe and Nora Bromley came from radically different backgrounds but overcame prejudices and obstacles to complete the vision of The Colony Club. It became a unique club for upper-class women to socialize and to gather together to exchange ideas to help effect social change including universal suffrage.

The Colony Club quickly outgrew its original home. These same forward-thinking innovators organized and built an equally grand, larger clubhouse located at 564 Park Avenue with additional amenities and a liquor license which opened in 1916 and continues to flourish today. In 1963, the original club became the East Coast headquarters of the American Academy of Dramatic Arts (AADA).

Shelley Noble consistently earns top marks for solid history achieved with thorough conscientious research combined with her remarkable gift for storytelling. Last year, her best-selling novel The Tiffany Girls garnered rave reviews for a riveting novel about the largely unknown female artists who crafted the glassworks studio iconic lamps. The Colony Club is certain to be a critical success and fan favorite. Readers like this reviewer may well emulate Alice and “go down the rabbit hole” for several days lost in a pleasant reverie of researching related topics. It’s a lovely book!

About Shelley Noble:

Shelley Noble is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of 16 novels of historical fiction, historical mystery and contemporary women’s fiction, including The Tiffany Girls, Ask Me No Questions, and Whisper Beach.

Shelley Noble is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of 16 novels of historical fiction, historical mystery and contemporary women’s fiction, including The Tiffany Girls, Ask Me No Questions, and Whisper Beach.

A former professor, professional dancer and choreographer, she now lives in New Jersey half way between the shore, where she loves visiting vintage lighthouses and carousels, and New York City, where she delights in the architecture, the theatre, and ferreting out the old stories behind the new.