The Last Tale of Norah Bow by J.P. White

Let’s set the scene; 1926, during Prohibition. Fourteen-year-old Norah Bow lives in Sandusky, Ohio, which as it turns out, is the prime location for rum runners from across the Canadian border. During a night walk along the beach, Norah stumbles into the rum runners, only to recognize her father among them. No words are spoken. Her love for her father is unwavering. But when three of the rum runners barge into the Bow dinner table a few days later and abduct Norah’s father, one secret is out.

As she watches her father be whisked off, though, Norah wonders to herself, “why did three men … hauling my daddy away with a black bag over his head, make me feel like I was already dead, but never more alive? These men, whoever they were, would not get away with this crime.” That night, she gathers supplies in the darkness and leaves her mother a simple note: Gone to bring him back.

And so, begins The Last Tale of Norah Bow by J.P. White — a rollicking adventure that captures the very spirit of the Roaring 20s. Here, we talk with the author about what it was like to write a story set in such a dynamic time, juggling everything from women’s suffrage to Prohibition and even something he refers to as “a demon switch” — something both Norah and her father possess.

Q: What drew you to set your story in 1926 during Prohibition? Do you have a personal interest in this era, and how did the historical context shape the characters and plot?

A: I had a cousin once say there was an alcoholic gene buried under the White family tree and it was planted there long before Prohibition. That line stuck with me and it made me want to explore how such an alcoholic gene might feed certain characters like my grandfather and grandmother on my father’s side who I never knew. The twenties did roar with changing attitudes toward women starting with the 19th amendment that was passed in 1920. This first wave of empowerment coincided exactly with Prohibition. The Ruby character represents, in part, a collision of these two social forces. Norah’s father is a self-described teetotaler but in reality, the flood of alcohol coming into the United States from Canada represents part of the temptation he can’t resist.

Q: Norah is young and intrepid. What challenges did you face in writing her journey from adolescence to maturity, especially as she navigates the dangerous and morally ambiguous world of rum-running? How did you ensure her development felt authentic?

A: I have three sisters and no brothers. In many ways I feel like I can track the female sensibility as well as the male. While writing Norah Bow, I was also a father to a teenage girl and my own marriage was beginning to falter. What’s more, I have always been close to my mother who was in mid-eighties when I started the book and was 97 at the time of her death. Start to finish, she and I were close and we tracked each other’s “memories, dreams and reflections.” That said, I gave myself permission to travel the life span of Norah and to imagine the pushes and pulls on her psyche as she reflects on the summer of 1926 when the first real storm of her life begins.

Q: The novel explores themes of family secrets and self-reliance. Were there any real-life inspirations for these themes? How did you balance them with the adventurous elements of Norah’s quest, and what message do you hope readers take away?

A: My father, who sold life insurance and never believed in it, once told me, there are three things that boggle 98% of the people: sex, death and money. The father in my story, Vital Bow, gets himself tangled with all three of these giants and is unable to share his entanglement with his family. Norah’s bond with her father is fierce. She believes she knows who he is, but soon discovers she doesn’t know him at all. From the first page, he tells her they both share a rare ability to access a demon switch — meaning they are capable of difficult things that other people can’t do. Vital is capable of vanishing into a well-guarded secret. Norah is capable of discovering the nature of that secret, no matter the cost. My hope would be that the reader might reflect on how such a demon switch might come to one’s aid while for another it might destroy everything in a family.

Q: The story is narrated by an elder Norah reflecting on her past. How did this narrative structure influence the pacing and the revelation of plot points? What challenges and advantages did you find in using this approach?

A: I wanted the story to be like a tale told around a fire. Something whispered, something urgent, a confession of sorts that needs to come out before the fire dies down. The elder Norah suggests she has very little time left or maybe just enough time to reveal what happened during the summer of 1926. The trick was to find a way to keep the engine of the main story running while also indicating that it’s a memory and a reflection, with pieces that might be lost or even invented. At one point, the book was much longer than it is now but the present moment was not as compelling as the past so I pared much of the present away and was left with the narrative strategy that I believe is attributed to Faulkner, “the past is always present.”

Q: Ruby Francoeur is described as an enigmatic woman with secrets of her own. Can you discuss her role in Norah’s journey and how her character challenges or complements Norah’s growth? Did you plan Ruby’s backstory from the beginning, or did it evolve during the writing process?

A: Ruby is a new woman of the 20’s and is, in fact, a late 20-something. She is a brash provocateur, unreliable siren and opportunist who has been on her own for a long while, a woman who lives dangerously in a world of men, money, sex and adventure. She is intended to be Norah’s Virgil who will help guide her through the inferno that Norah must enter to retrieve her father. At the same time, Ruby always looks out for Ruby first. This revelation is part of the coming-of-age discovery that Norah comes to.

Adults will disappoint and astonish, help and hurt, hide and seek, almost in the same moment. Norah wants to imagine that people are basically good, but Ruby assures her that people are never who they appear to be. What Norah doesn’t know is that Ruby is speaking truth about herself.

Q: The book deals with the complicated nature of memory. How did you approach portraying the reliability or unreliability of Norah’s recollections, and what role does memory play in shaping the narrative?

A: One of the bonus extras of aging is how few people are left who can cross-examine the details of your reportage, how if you leave something out or put something in, almost no one is left alive who can flag embellishments as errors or claim no such thing ever happened. As the oldest of the old, Norah knows of these limitations. Throughout her telling of her “fireside” story, she suspects she is not seeing enough of what she thought she saw and felt. Brain science tells us that every time we retrieve a memory, we tweak that fragment to suit the weight and shape of the moment. Before she dies, she wants, needs and deserves to be free of what happened during the summer of 1926 between her and her father. The underlying question of the book is whether that freedom finds her or whether she still feels entrapped at the end.

RELATED POSTS:

Girl’s Search for Abducted Father in Prohibition-Era Coming-of-Age

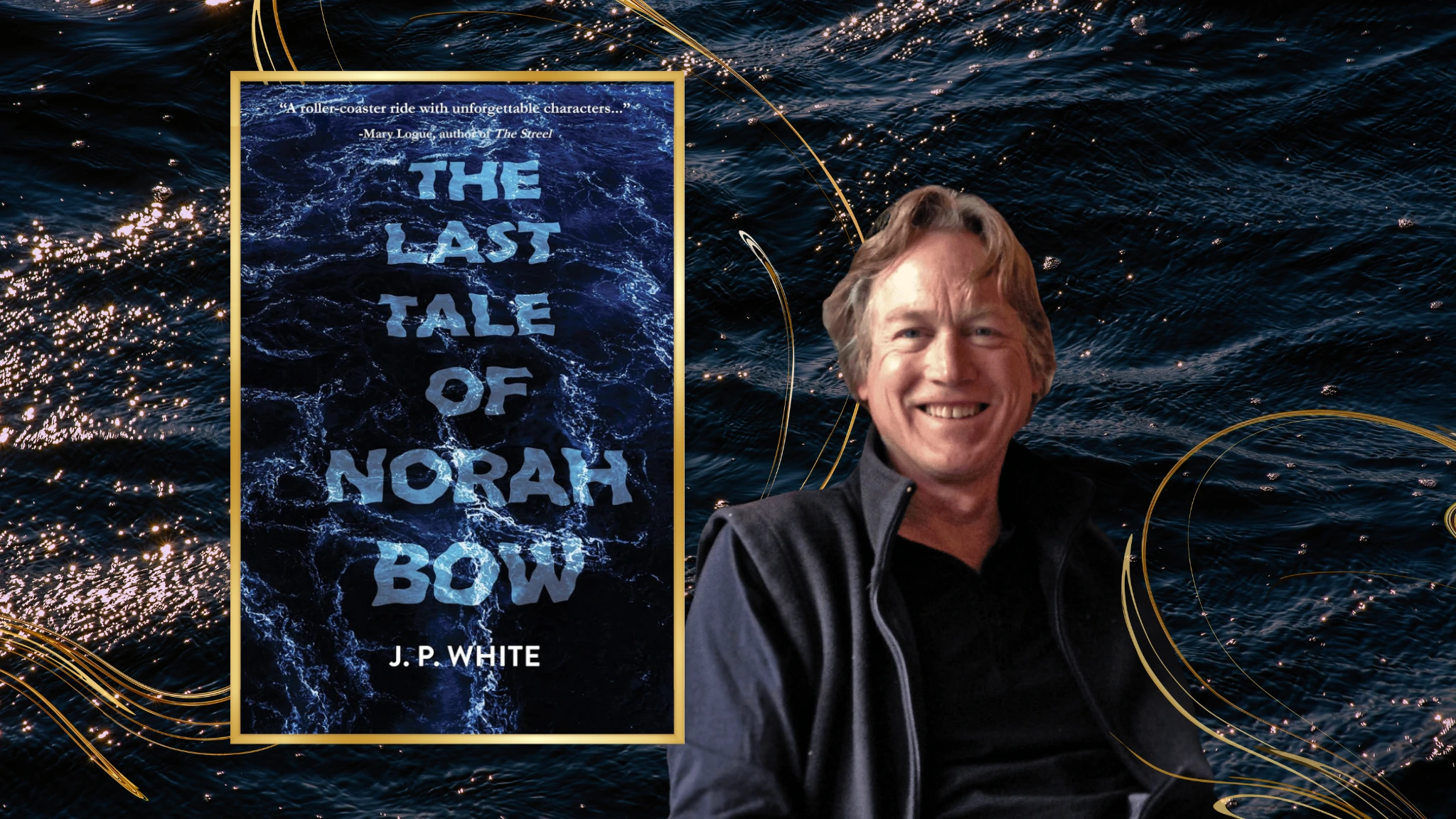

About the Author:

About the Author:

J.P. White has published essays, articles, fiction, reviews, interviews, and poetry in over 100 publications, including The Nation, The New Republic, The New York Times Book Review, The Los Angeles Times Magazine, The Gettysburg Review, American Poetry Review, and Poetry (Chicago). A highly acclaimed, award-winning writer, White pushes beyond the boundaries of the lyric/narrative tradition to let more of the flux and wonder of the human condition rush in.

He spent his childhood summers sailing on Lake Erie. In the early 1980s, he worked delivering sailboats up and down the Eastern seaboard, to the Bahamas and the Caribbean. He currently sails a Cape Dory 25D out of St. Louis Bay on Lake Minnetonka, near Minneapolis. Visit jpwhitebooks.com.