Keeping the Faith by Brenda Wineapple

The sensational “monkey trial” of 1925 didn’t actually concern monkeys. The issue was whether a young schoolteacher in rural Tennessee had violated state law by teaching the scientific theory of evolution to his public school students.

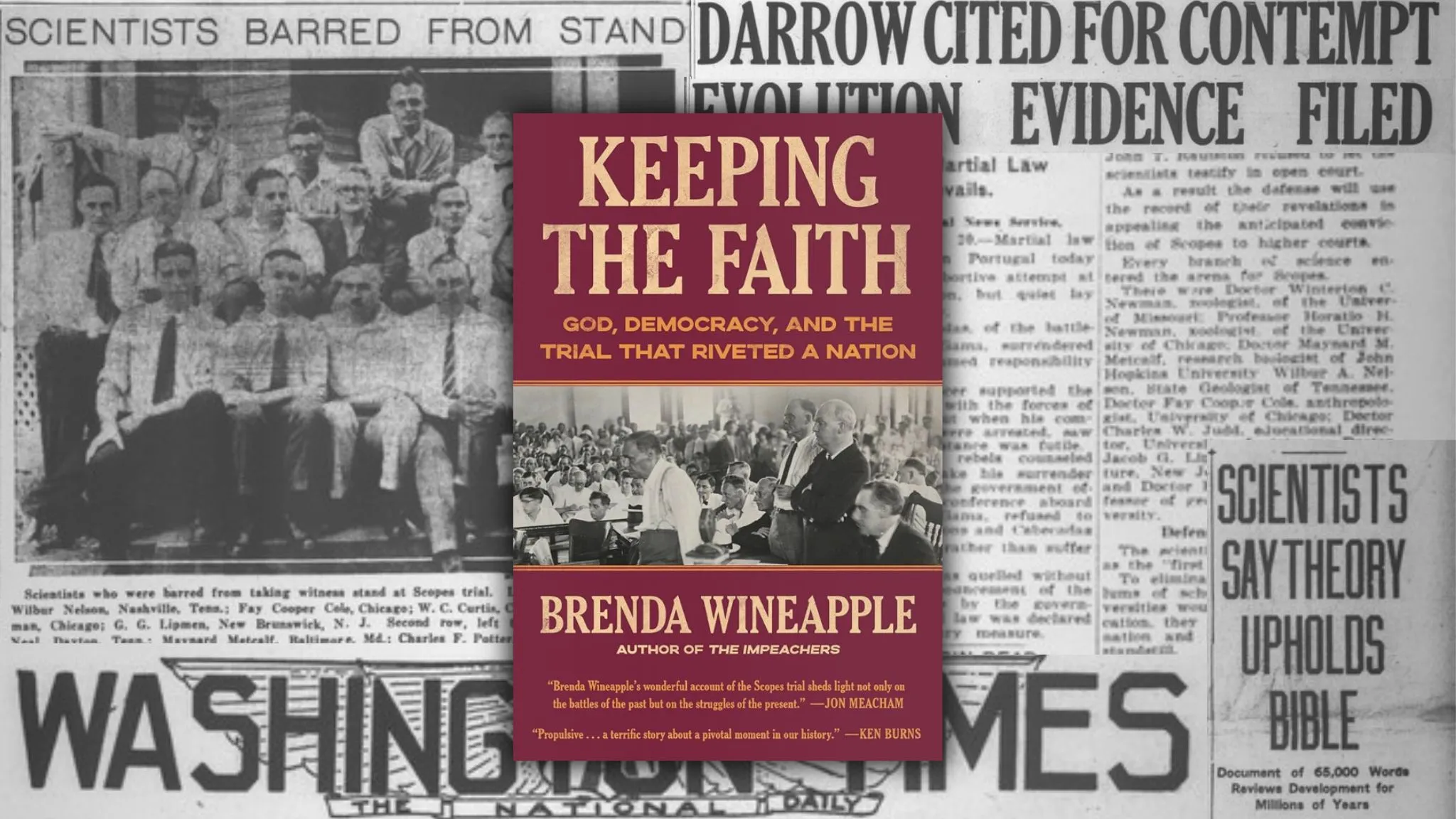

In her new history of the Scopes Trial, Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial that Riveted a Nation, scholar Brenda Wineapple gets a jump on the trial’s centennial with a compelling story that reveals as much about cultural and social change in America as it does about science.

The English naturalist Charles Darwin traveled the world, most famously the Galapagos Islands. A close observer and empiricist, he developed a theory that became known as “survival of the fittest.” Darwin argued that all organisms adapt to their environment in order to survive, evolving over time through natural and sexual selection. Further, all species — including humans — share a common ancestor. Darwin explained his ideas in The Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871).

Unsurprisingly, the theory of evolution soon made its way into the science curriculums of high schools and colleges. Challenged by an industrializing society, science was booming with medical discoveries and new interpretations of human behavior and the mysteries of the universe. Psychoanalysis, quantum physics, the theories of relativity and continental drift, and cures for syphilis and diabetes were among many early 20th-century breakthroughs.

Not unlike divergent responses to the Covid pandemic, however, the rising authority of science posed a threat to many Americans. It’s easy to understand why Darwin’s theories, in particular, would be considered heretical. They challenge religious belief in the divine creation of man. Fundamentalist Christians who invoke Scripture as the sole standard for truth naturally reject scientific rationalism.

History of the Scopes Trial

Which leads to the spring of 1925 in the Cumberland Mountains, where the small city of Dayton, Tennessee awaited the trial of 25-year-old teacher John Thomas Scopes. Americans were excited about the “science vs. religion” face-off. The trial would be the first to be broadcast live on radio and news coverage was immense. Yet most of the 1,800 local residents did not yet grasp that the trial, for all its import, would transform their quiet world into a spectacle.

As the legal teams convened, two famous lawyers stepped forward: William Jennings Bryan for the prosecution and Clarence Darrow for the defense.

An evangelical minister and superb orator who grew up in Nebraska, Bryan was a former Secretary of State who ran for president (and lost) in 1896, 1900, and 1908. Bryan’s lectures and revivals had brought him considerable wealth but he was in poor health and died five days after the trial concluded. Wineapple more or less labels Bryan a racist and quotes his biographer: “Bryan’s passion for democracy always cooled at the color line.”

The Chicago lawyer Clarence Darrow, rumpled and brilliant, had made his reputation defending labor unions. Darrow believed fervently in the work of democracy. “Stand up and demand your rights as citizens,” he told Jewish peddlers who were harassed while the Chicago police watched with indifference.

Darrow believed that “law was a luxury bought and sold,” Wineapple notes, “and those who pay the most receive the most.”

Controversy Driven by Social Change

In the popular imagination (including the 1960 film Inherit the Wind), the Scopes Trial is often reduced to a battle between Bryan and Darrow. Yet as influential as these men were, Wineapple shows that cultural and social change drove the controversy and created conflicts similar to those we face today surrounding public education, immigration, and the First Amendment.

The 1920 Federal Census was the first to show that the U.S. population had shifted dramatically: more Americans lived in urban than rural areas. Those who did not, regarded cities with skepticism and concern. Cities were home to modern movements in music, literature, and art. Cities flouted tradition, rejecting the authority of the church and school and welcoming new fashion, manners, and ideas. Cities generated early mass media, which brought forth popular culture.

At the same time, Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan flourished. Higher learning, credentials, and expertise drew suspicion. Advocacy organizations like the ACLU — which funded the Scopes defense — and the NAACP were branded as agitators. Bryan did not believe in the separation of church and state, and he had many followers.

Thus when Bryan and Darrow squared off in sweltering heat on the second floor of the Rhea County Courthouse in July 1925, they represented more than their individual clients. They represented constituencies who held opposing views about change. The author certainly persuaded me that the acceptance or rejection of the theory of evolution was emblematic of that divergence.

This illuminating, important story is out of the past but it lands in the present.

About Brenda Wineapple:

Born in Boston and raised in northern Massachusetts (on the New Hampshire border), Brenda has lived in New York City for many years with her husband, the composer Michael Dellaira.

Born in Boston and raised in northern Massachusetts (on the New Hampshire border), Brenda has lived in New York City for many years with her husband, the composer Michael Dellaira.

There, she does her writing, and most recently, in Keeping the Faith, she has delved into a single momentous event in American history, a trial momentous in its own time, important in ours, but largely unknown, forgotten, or belittled.