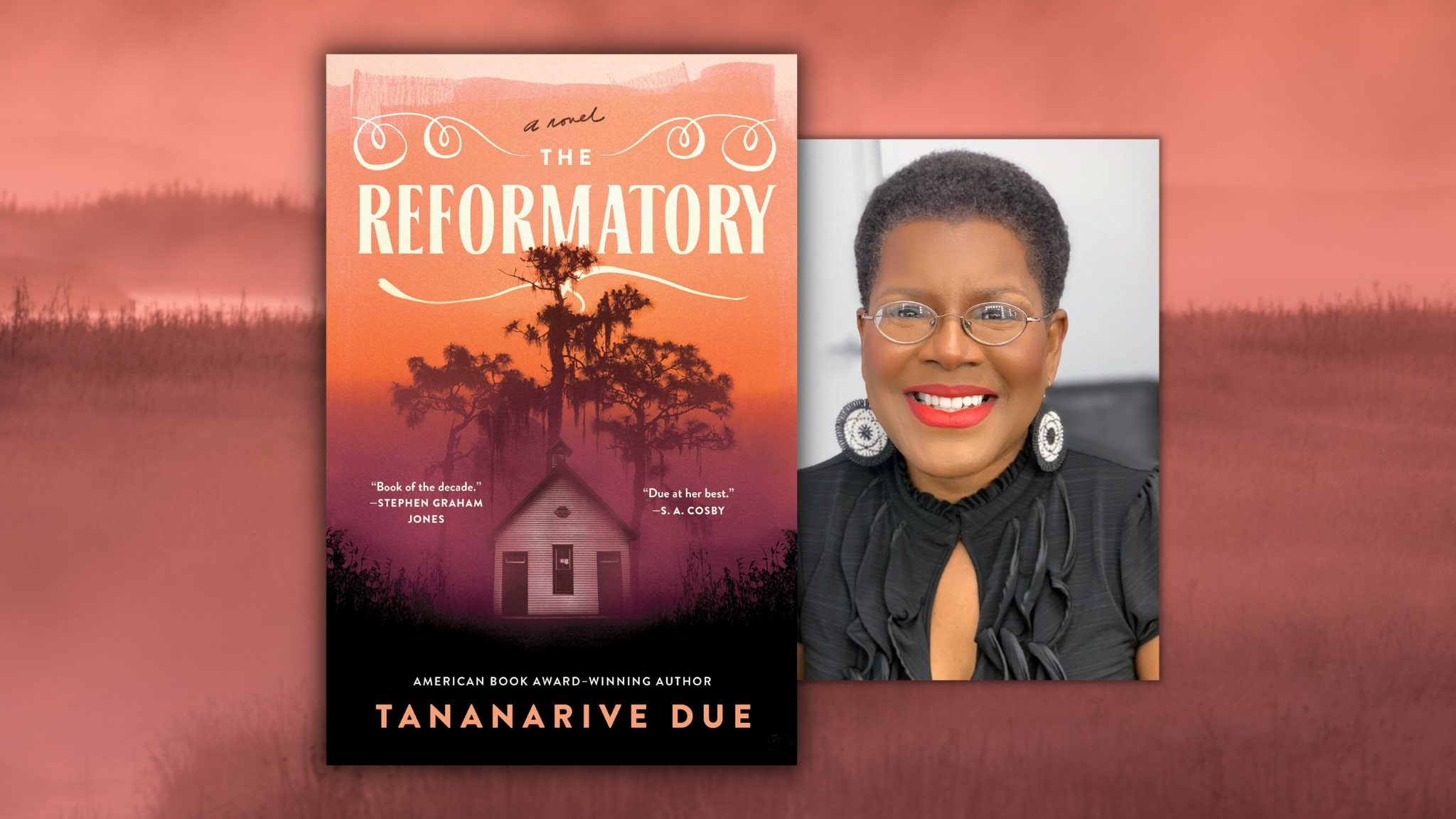

Tananarive Due’s new novel, The Reformatory, had an auspicious publication date: October 31st. It’s long been said that the line between the living and the dead is at its thinnest on Halloween night—a belief fitting of her story, given the ghosts (or “haints”) she resurrects within its pages. A seven-plus year labor of love and languish, the book—which melds the history and horrors of the Jim Crow South—was loosely inspired by Due’s great-uncle, who died at Florida’s Dozier School for Boys in 1937.

The Reformatory’s protagonist, twelve-year-old Robert Stephens Jr., has been sentenced to a six-month stay at the (fictional) Gracetown School for Boys after having defended his sister’s honor against a white peer from a prominent family. Told to keep his head down and his mouth shut, he nevertheless catches the attention of the school’s tyrannical superintendent, who realizes Robert can see the spirits that haunt the school’s grounds. Caught between loyalty to the haints (who include his recently deceased mother) and the desire for self-preservation, Robert’s plight soon becomes a matter of life and death—and not just his own.

The author—a recipient of an American Book Award, an NAACP Image Award, and a British Fantasy Award, and daughter of civil rights activist Patricia Stephens Due—learned early on that “horror can be a healing balm after trauma.” It’s an idea that infuses her novels and short stories as well as the podcast she hosts with her husband, Steven Barnes (“Lifewriting: Write for Your Life!”), and the Black Horror and Afrofuturism courses she teaches at UCLA. Recently, Due reflected on this, and The Reformatory’s amalgamation of fact, fiction, and folklore.

The Reformatory is a work of imagination that’s grounded in the brutal realities of the Jim Crow South. Why did you decide to revisit that shameful period of history at this moment in time, and in what ways does having used the lens of fiction allow for a more palatable reading/writing experience than non-fiction might?

Horror, to me, is an escape from the harsh realities of life. So, when I learned that I had a great-uncle, Robert Stephens, who died at the Dozier School for Boys in 1937, I wanted to use the realm of fiction to give him a different story. Although it’s a ghost story, and Robert and the other children are afraid of “haints,” it’s definitely Jim Crow and the warden who are the true monsters in this story. But I also definitely wanted to use ghosts and a fantasy element to try to blunt the pain of the true-life monstrosity.

The book was inspired by your great-uncle, who was presumed dead after he disappeared from Florida’s Dozier School for Boys. What compelled you to explore this mystery, albeit fictionally, and did you find that doing so brought any level of catharsis or closure to that chapter of your family history?

Actually, my great-uncle didn’t disappear—he allegedly died after being stabbed by another prisoner and was buried at the Dozier School’s Boot Hill. So, this was never about trying to solve a mystery. My endeavor was to try to honor his name and experience symbolically as a child who was imprisoned and died at this facility—but to completely fictionalize the story otherwise. This was never an attempt to look through historical records and find his story; instead, I used what I knew of his story to create a work of fiction to help his name live on.

The two characters at the heart of the book are twelve-year-old Robert Stephens Jr. and his older sister, Gloria, who feels responsible for him. What appealed to you about exploring the dynamics of a sibling relationship such as theirs, and how does their tender age help to underscore the profound abuses they encounter?

I write a lot of child protagonists, so that’s one of the things that drew me to the story of Robert Stephens. I made him 12 instead of 15 to make him younger and even more vulnerable, which is true to life in the sense that very young children were imprisoned at the Dozier School, as well as young men up to the age of 21. I love Robert’s optimism and sense of childlike play even when he’s in terrible circumstances. His older sister, Gloria—who carries my mother’s middle name—is having a very different coming of age story because of her responsibilities to Robert and her attempts to free him using systems that are actively hostile to Black people.

Speaking of those abuses: What was your approach to depicting instances of emotional, physical, and/or sexual trauma with both realism to the times and sensitivity to the reader? And how did you endeavor to maintain lightness in your own life while vicariously exploring such darkness on the page?

It took me more than seven years to write this novel, in part, because the research—reading memoirs by survivors—was so heartbreaking. Although survivors have alleged that the facility had a “rape room” used by guards to abuse the children, there was no way I wanted to depict anything close to that in this novel. It’s too triggering for me, and it’s too triggering for readers. Any violence I depicted against children in the whipping shed was very difficult to write, and although it was based on accounts I heard first-hand from survivors, it was still a tough scene.

My fear was that using too gentle a hand would be a dishonest rendering of the facility, although it’s fictionalized. I didn’t want to candy coat it too much, but I also didn’t want to make it too difficult to read. So instead of depicting sexual assault, for example, I dropped hints about the horrors that might be contained in the psychopathic warden’s trophy photographs.

Throughout the story, you also introduce characters (Miss Anne, Mrs. Hamilton, etc.), both major and minor, who risk their own lives and/or reputations to defy authority/denounce injustices. Tell us about the importance of representing these individuals and what it illustrates about the cumulative impact of their contributions, however small, on the collective whole?

This novel is set in 1950, but I definitely wanted The Reformatory to be in conversation with people today who are wrestling with an unjust criminal “justice” system and growing tides of open racism as a backlash to Barack Obama’s presidency. So many people feel overwhelmed and wonder, “What can I do?” So many people are afraid to put themselves at risk. I drew on the examples from my parents’ civil rights activism to try to show that people can be heroes and heroines in big and small ways, and they can be cowardly and villains in big and small ways.

Though The Reformatory transcends genre (as most books do!), it can be considered a work of horror in addition to historical fiction. Beyond visceral scares, what unique qualities do you think that horror stories in general—and ghost stories specifically—offer their audience? How can they be of benefit to the psyche vs. simply tormenting it?

I learned from my late mother, Patricia Stephens Due, that horror can be a healing balm after trauma. She loved horror and passed that love on to me. Now, for example, I’ve noticed that horror films centered around caregiving—where a demon or monster is introduced—help soothe me as my 88-year-old father, John Dorsey Due, Jr., is aging. Horror helps a lot of us believe that no matter what we’re going through, at least it isn’t as bad as THAT. We can also draw upon the lessons from characters who rise to their challenges and fight back against forces that are much bigger than they are.

In addition to being a novelist, you also teach, write for the screen, and host a podcast with your husband. Despite their surface-level differences, how do you find that these disciplines both inform one another and influence your evolving abilities and ambitions as a storyteller?

Absolutely! Storytelling can take many forms, whether it’s true-life storytelling on a podcast, finding different ways to express the same idea in a comic, script, or prose, or helping students learn the social impact we can achieve through stories.

Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

I’ve written a spec script called Bear Creek Lodge, expanded from my World Fantasy Award-nominated short story, “Incident at Bear Creek Lodge.” While we try to sell it as a script, I’ll be getting to work on it as a novel.

About Tananarive Due:

Tananarive Due (tah-nah-nah-REEVE doo) is an award-winning author who teaches Black Horror and Afrofuturism at UCLA. She is an executive producer on Shudder’s groundbreaking documentary Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror. She and her husband/collaborator, Steven Barnes, wrote “A Small Town” for Season 2 of Jordan Peele’s “The Twilight Zone” on Paramount Plus, and two segments of Shudder’s anthology film Horror Noire. They also co-wrote their upcoming Black Horror graphic novel The Keeper, illustrated by Marco Finnegan. Due and Barnes co-host a podcast, “Lifewriting: Write for Your Life!”

Tananarive Due (tah-nah-nah-REEVE doo) is an award-winning author who teaches Black Horror and Afrofuturism at UCLA. She is an executive producer on Shudder’s groundbreaking documentary Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror. She and her husband/collaborator, Steven Barnes, wrote “A Small Town” for Season 2 of Jordan Peele’s “The Twilight Zone” on Paramount Plus, and two segments of Shudder’s anthology film Horror Noire. They also co-wrote their upcoming Black Horror graphic novel The Keeper, illustrated by Marco Finnegan. Due and Barnes co-host a podcast, “Lifewriting: Write for Your Life!”

A leading voice in Black speculative fiction for more than 20 years, Due has won an American Book Award, an NAACP Image Award, and a British Fantasy Award, and her writing has been included in best-of-the-year anthologies. Her books include Ghost Summer: Stories, My Soul to Keep, and The Good House. She and her late mother, civil rights activist Patricia Stephens Due, co-authored Freedom in the Family: A Mother-Daughter Memoir of the Fight for Civil Rights. She and her husband live with their son, Jason.

(Photo Credit: Melissa Herbert)

This story appears through BookTrib’s partnership with the International Thriller Writers. It first appeared in The Big Thrill.