(Note: This article contains mild spoilers for My Heart is a Chainsaw.)

(Note: This article contains mild spoilers for My Heart is a Chainsaw.)

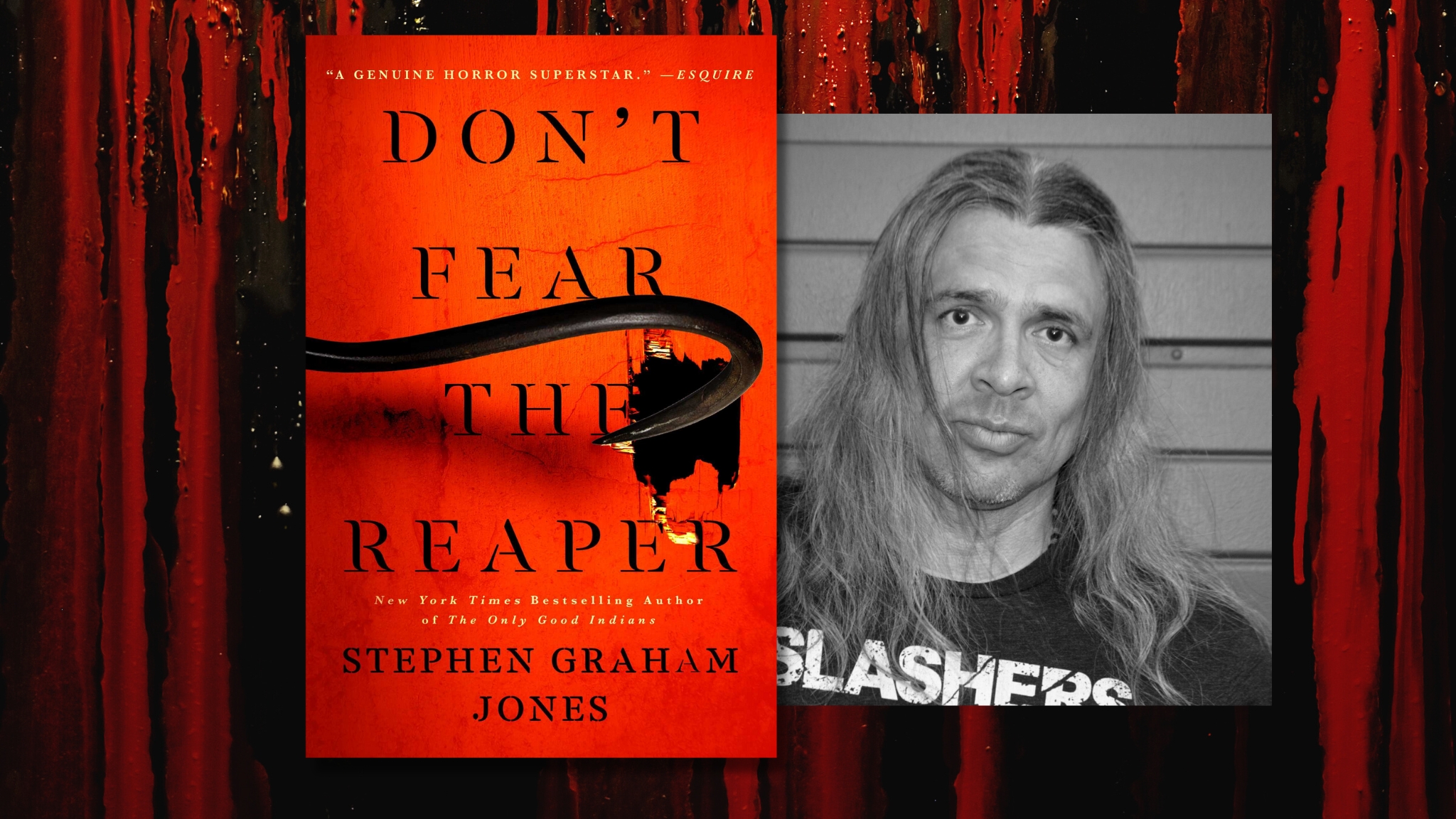

Stephen Graham Jones knows how to write a killer novel.

My Heart is a Chainsaw, the first novel in The Indian Lake Trilogy was a summer slasher — end-of-school parties, teenage hijinks on the lake, tales about the haunted summer camp on the hill and of course, the not-so-mythic story of the Lake Witch, Stacey Graves. The summer ended on July 4th, with a brutal slaughtering to rival Jaws — what soon became known as the Independence Day Massacre.

Four years after the deadly day, Jennifer “Jade” Daniels has served her time, returning to Proofrock, Idaho with her shaved head grown out and her high-school obsession with classic slasher films buried — for now. Letha Mondragon, Jade’s idea of the quintessential final girl, is still there, changed in more ways than one.

The sequel, Don’t Fear the Reaper, brings with it Dark Mill South, a serial killer who has escaped from prison, seeking revenge for the killing of 38 Dakota Men in 1862. With textbook knowledge of the horror films that shaped Jade’s adolescence, Dark Mill South is the perfect opponent for these final girls.

The sequel, Don’t Fear the Reaper, brings with it Dark Mill South, a serial killer who has escaped from prison, seeking revenge for the killing of 38 Dakota Men in 1862. With textbook knowledge of the horror films that shaped Jade’s adolescence, Dark Mill South is the perfect opponent for these final girls.

And if Chainsaw is summer, Reaper is winter. Through a blizzard, Jade and Letha must fight, hand in hand, to hold off the slasher in a cycle that just keeps repeating itself.

As a staple of horror, particularly slashers, Jones’ novels are full of graphic visuals — from body horror, to supernatural creatures, to a spoilery scene in Chainsaw involving a pile of dead elk.

In an interview for BookTrib, I asked Stephen Graham Jones about the research he does to craft the gore in his novels.

“Been hunting all my life, so I know what the insides of mammals look like pretty well. Especially elk and all the kinds of deer. And I grew up farming, too, so there were always dogs and cats meeting terrible, quite visual, Saw-type ends. Not intentional stuff, just, small animals skirting around huge equipment.

“When I was … maybe thirteen, I guess? Right around then, we were living in a little house one of my great uncles owned, and it was right beside an old horse trap — just a long narrow sort-of corral, sort-of pasture — that wasn’t being used as a horse trap anymore, so it became where all the livestock that got hit on the road or otherwise died got dragged, to rot away, because who’s gonna bury a horse (though there is a good poem about doing just that…).

“That horse trap was a playground for me. And a school, too. I spent so many afternoons after the bus dropped me off crawling all over and inside those rotting cows and bulls, steers and horses. I used to pull parts off them and keep them in different boxes, so I’d have a stash of these, a stash of those. Not sure what ever happened to those boxes.

“Around the same time and age, we were living out in the trees around Wimberley, Texas, and the house we were renting came with all these goats for some reason. They were fun to wrestle with, but the neighbor dogs would always come run them down, hamstring them the way town dogs do, where they’re just killing, not eating. So I’d go out and sit with those dying goats, keep a pan of water for them to lap at, and finally they’d die in my lap.”

Now if readers can’t stomach that, they’re better off far away from the brutal and downright killer gore in this series.

What I’m uniquely compelled by is those first victims in his novels. Jones doesn’t send nameless characters off to die for the purpose of introducing the slasher. In Chainsaw and Don’t Fear the Reaper, we follow high schoolers in the town, participating in harmless fun — and then we watch them die brutal deaths, as he keeps the literary “camera” on them for just a few more moments.

Why keep them alive right before they succumb to their injuries? Is there a greater metaphor there about living through the horrific and unspeakable? Or is it all for the sake of fun and gore?

“Just to make it hurt more. Horror’s got to hurt. Not just your gut, but your soul.”

And hurt it does, especially when you care about the characters. Jade Daniels and Letha Mondragon are impossible not to love — which raises the stakes that much higher as they’re pitted against an opponent hungry for blood, facing both human and inhuman dangers.

Where do you find that balance between the supernatural and the realistic?

“The real real that’s always most important for me to get right is the emotional. If a story doesn’t have the feels, then why are we even reading it? So, that’s first. As for the realistic, you also have to land that, in horror. It’s how you scare the reader, by suggesting that this backdrop matches their own backdrop, meaning … the horror can slide from backdrop to backdrop, can’t it? At least at two in the dark morning, it can.

“As for the supernatural, I always consider that the eruption of the ‘wrong’ into our space, disturbing our sense of reality. And it’s great to deploy, just, at least with horror (as opposed to fantasy, or to dark fantasy), don’t get too wrapped up in the rules of the system. Once there starts to be rules, those are basically tethers, binders, fences. And horror’s less scary when it has to be like that.

“So? I guess my hierarchy is land the feels first, then make the place as real and recognizable and particular as I can get it, and then mess everything up with something wrong.”

Sometimes, reality can be just as terrifying. Jones has crafted credible supernatural threats, but the real-world ones are just as sinister. In an interview with The Big Thrill, Jones spoke about trying to repair “the slasher’s idea that women’s bodies are disposable” in crafting his lead character, Jade. In My Heart is a Chainsaw, he tackles themes of rape and sexual assault through the metaphor of the slasher, and in Don’t Fear the Reaper, he handles the aftermath.

How did you know Jade was someone who had to (or even could) be a survivor, in both senses of the word?

“Initially, she wasn’t, she just hated her dad. But then she really hated him, so I had to dig back, see the why of that. And? Turned out Tab was a Bad Dude, a terrible father. I didn’t want to fall back on that old thing of the woman’s function in the story is to suffer sexual trauma or be pregnant, which we see so, so much, just because women get treated as objects on the page, not people, but, too, I didn’t think I could shy away from who Jade was. She’s formed her identity as a result of what happened to her. So, my ‘balance,; I guess, was to do everything I could not to re-inscribe that trauma. Which, in fiction, means not sensationalizing the act, not getting all needlessly, showoffily granular with the terrible details. I think I would be as bad as Tab, were I to do that.”

Jade is not the only survivor after the events of My Heart is a Chainsaw — all of Proofrock is grieving. Don’t Fear the Reaper touches on the concepts of community grief and generational trauma as the town reckons with the massacre.

Is the series heading towards a conclusion or a focal point on these themes, or is it more of a meditation on or exploration of them?

“Man, you’d have to ask my editor at Saga, Joe Monti, about that. He thinks that stuff through. I just try to pour adrenaline and emotion on the page. Like, with Chainsaw, I gave it to him, and he said, ‘Hunh, neat. Gentrification as a horror story.’ I kind of opened up a side tab on my browser, searched ‘gentrification’ up to make sure I had it down right, and told him, ‘Yeah, you bet, sure, of course, that.’ But, really, I never think about that kind of stuff while writing. Suspect I’d do something not-fiction, if I did.”

What is carefully and intentionally crafted in Chainsaw and Reaper is the slasher cycle itself, which acts as a character in the series — it has wants and needs, giving the story a fated, out-of-anyone’s-control feeling. The events feel inevitable, yet the characters do their best to resist and fight back.

When a story is doomed to repeat itself — with the characters trapped inside — how do you keep it fresh?

“Yeah, that’s the hard part, for sure. The trick is keeping the reader wrong-footed. You lay out the conventional build, say, and have the characters all subscribe to it, believe in it, run from it, when — surprise! — it was actually this other build the whole time. Or? You feint like it’s going to be that ‘other’ build, let the reader think they’re seeing behind the curtain, when … it was the conventional way all along. It’s like that talk Randy and Dewey have in that eating place in Scream 2, where satisfying expectations is the double-reverse trick. I love it.”

You’ve spoken in other interviews about having playlists for each of your novels, and you’ve already shared your Don’t Fear the Reaper playlist. What songs were featured on your writing soundtrack for The Angel of Indian Lake?

“Mostly different ones. More Taylor Swift than I would have thought, and a lot of bands I don’t really know: Offspring, My Chemical Romance, Halestorm, She Wants Revenge. They’re all there because I built this playlist off of a Books in the Freezer (podcast) ‘Final Girl’ playlist, when the one I’d used for Chainsaw and Reaper wasn’t cutting it. And it was perfect, got me through most of Angel.”

Is there anything else you can tell us about The Angel of Indian Lake and finally concluding the Indian Lake Trilogy? Are there any other upcoming projects you’re working on?

“I’m working on I Was a Teenage Slasher, yep. It’s the next novel after Angel. Just wrote a story nobody’s asking for, which is always the most fun kind to write. And, Angel — not sure what I can and can’t say, but, if it’s like the previous two in the trilogy, then I can’t say much.

“Though? My perfect tagline for it, which I don’t know if it’ll get used, is ‘It’s time to say goodbye to Jade Daniels.’ Which so breaks my heart. Hopefully, it breaks some other people’s, too. And then, maybe, if everything’s balanced just right, knits it back together.”

Don’t Fear the Reaper is out now in paperback from Gallery/Saga Press.

About Stephen Graham Jones:

Stephen Graham Jones is the New York Times bestselling author of The Only Good Indians. He has been an NEA fellowship recipient and been recipient of several awards including: the Ray Bradbury Award from the Los Angeles Times, the Bram Stoker Award, the Shirley Jackson Award, the Jesse Jones Award for Best Work of Fiction from the Texas Institute of Letters, the Independent Publishers Award for Multicultural Fiction, and the Alex Award from American Library Association. He is the Ivena Baldwin Professor of English at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Stephen Graham Jones is the New York Times bestselling author of The Only Good Indians. He has been an NEA fellowship recipient and been recipient of several awards including: the Ray Bradbury Award from the Los Angeles Times, the Bram Stoker Award, the Shirley Jackson Award, the Jesse Jones Award for Best Work of Fiction from the Texas Institute of Letters, the Independent Publishers Award for Multicultural Fiction, and the Alex Award from American Library Association. He is the Ivena Baldwin Professor of English at the University of Colorado Boulder.

(Photo Credit: Stephen Graham Jones)